Last summer, a group of Tim Hortons franchisees, known as the Great White North Franchisee Association (GWNFA), took their parent company, Restaurant Brands International Inc. (RBI), to court. The restaurant owners filed two lawsuits, alleging that RBI misused marketing fees, tried to intimidate franchisees into submission, and failed to help individual restaurants cover rising costs.

One of these growing costs, of course, belongs to labor. At the beginning of this year, the minimum wage in Ontario jumped from CAD11.60 to CAD14.00 an hour (~$1.90 increase), which the GWNFA estimated would cost each restaurant approximately CAD250,000 (~$197,833). RBI did not authorize stores to raise prices to make up the difference, so some Ontario locations decided to stop paying employees for their breaks and to reduce workers’ hours.

Other costs are chain specific. In late 2016, the coffee-and-donut giant announced that its stores would begin offering higher-end drinks, hoping to compete not only with Starbucks but also with McDonald’s, which started improving its McCafé offerings in 2015. Upgrading store systems came with a hefty price tag (CAD12,000/~$9,496), all paid for by the franchisee.

The GWNFA and RBI clashed again over the launch of Tim Hortons’ mobile app. Franchisees claimed that the company hadn’t fully tested it and worried that they would be overwhelmed by digital orders. In this instance, the store owners prevailed, and RBI delayed the launch by four months.

These three conflicts — minimum wage increases, elevated offerings at quick-service restaurants, and digital ordering — nicely capture how the Canadian foodservice marketplace is changing.

State of the Canadian Foodservice Industry

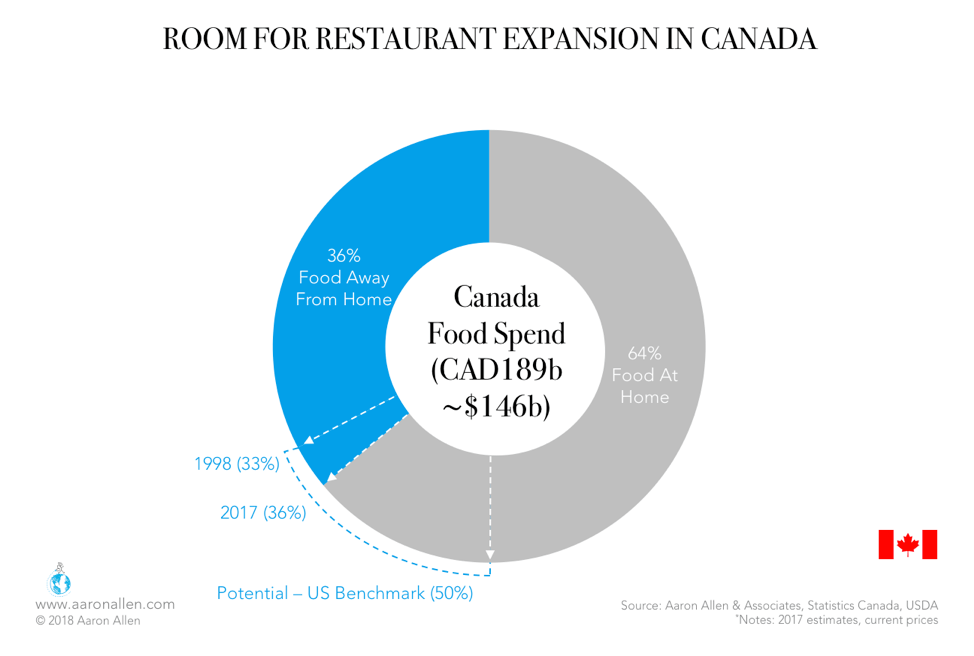

Over the past three years, Canadian food spend has increasingly gone to restaurants, bars, and other dining establishments. This category, known as food away from home (or FAFH), has grown 3 percentage points since 1998. In 2017, Canadians spent CAD68b (~$54b) at restaurants, cafés, and bars.

The growth is impressive, but there’s still room for expansion. Americans spend 50% of their food budget on FAFH. By this benchmark, the Canadian restaurant industry could still claim an additional 14 percentage points of total food spend, which would equate to an additional CAD26.5b ($21b) a year. As consumers are increasingly busy, they favor convenience, which is producing a global trend toward higher shares of FAFH.

In 2016, growth in the Canadian foodservice industry was dominated by fast and convenient options in the limited-service (LSR) category. Last year, however, full-service restaurants (FSRs) caught up and actually outpaced LSR growth by .3 points.

We’ve written before about how LSRs are reshaping the foodservice industry, and that’s happening in Canada, too. Since 1998, LSRs have captured an additional 5.9 percentage points of market share and now account for almost half the industry. These gains came from FSRs (which lost 1.8 percentage points) and drinking places (which lost more than twice that, 3.8 percentage points), showing that today’s consumers are spending money on food they can grab on the go.

Even as LSRs are reshaping the Canadian food market, the market itself is being reshaped by minimum wage increases. In three of the four largest provinces (Ontario, British Columbia, and Alberta), wages are rising quickly. Alberta will reach CAD15 (~$11.87) first, in October of this year, followed by Ontario (on January 1, 2019) and British Columbia (June 1, 2021, where the minimum will go up to CAD15.20/~$12.04).

These rising labor costs are complicating restaurants’ budgets. Since increasing efficiency without investing in technology is unlikely, one way to compensate for a wage increase is to increase prices. Some independent restaurants are laying off more workers than usual or hiring experienced employees in hopes of avoiding costly training programs.

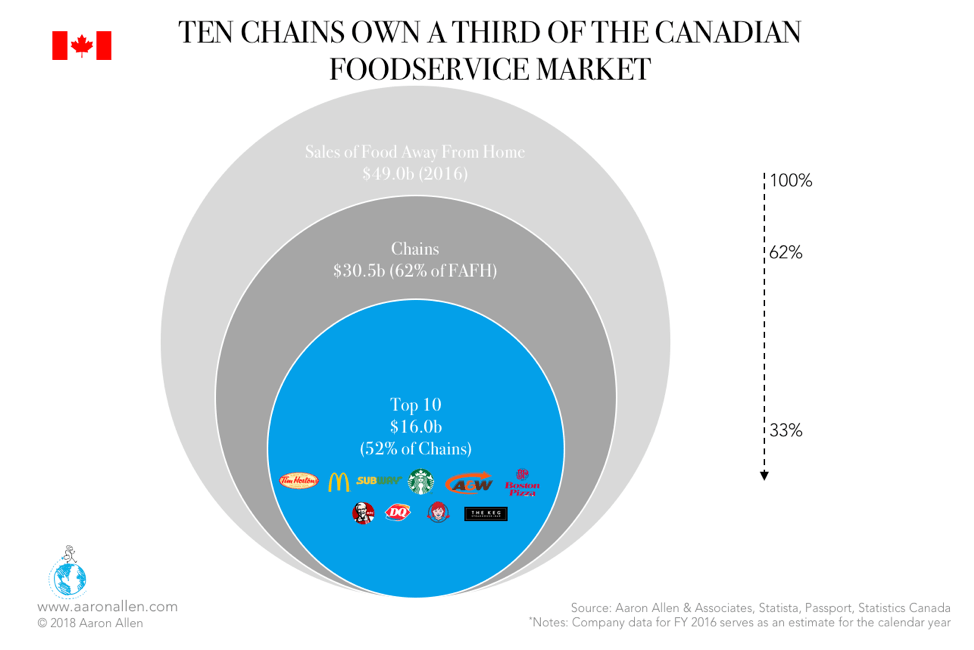

As they do all over the world, chains also play a major role in the Canadian foodservice industry. In fact, with $16b in sales in 2016, the top 10 Canadian chains control a third of the market — much more than the US chains, which only claim 15%.  Over the past few years, consolidation has increased among chain restaurants. MTY Group made 8 major acquisitions in 2017, with 3 in the burger segment (The Works, The Counter, and Built Custom Burgers) and 5 with most locations in Quebec (Steak Frites, Giorgio, Houston Avenue Bar & Grill, Industria Pizzeria & Bar, and Dagwoods Sandwiches & Salads). MTY also initiated a combination with Imvescor, another portfolio of brands that includes the steakhouse Baton Rouge, rotisserie-chicken mainstay Scores, and breakfast-and-lunch chain Ben & Florentine. And so far in 2018, MTY has scooped up Timothy’s World Coffee, Mmmuffins, and the U.S. chain Grabbagreen.

Over the past few years, consolidation has increased among chain restaurants. MTY Group made 8 major acquisitions in 2017, with 3 in the burger segment (The Works, The Counter, and Built Custom Burgers) and 5 with most locations in Quebec (Steak Frites, Giorgio, Houston Avenue Bar & Grill, Industria Pizzeria & Bar, and Dagwoods Sandwiches & Salads). MTY also initiated a combination with Imvescor, another portfolio of brands that includes the steakhouse Baton Rouge, rotisserie-chicken mainstay Scores, and breakfast-and-lunch chain Ben & Florentine. And so far in 2018, MTY has scooped up Timothy’s World Coffee, Mmmuffins, and the U.S. chain Grabbagreen.

Not to be outdone, Cara Operations bought the Quebec-based rotisserie-chicken chain St-Hubert in 2016, Toronto-centered Pickle Barrel in 2017, and, in January 2018, the Keg, 1 of 2 FSRs among the top 10 Canadian chains.

Foodservice in Canada is changing quickly. Companies must find new ways of setting themselves apart from the competition without losing sight of the core value of the hospitality industry: service. Here are three guiding principles to help restaurants thrive in this new marketplace.

1. Learn from Casual Dining’s Mistakes

As we’ve detailed before, the U.S. casual-dining (CDR) segment has been cannibalized by coffee shops and fast-casual restaurants. While some executives blamed this trend on a “restaurant recession,” the truth has less to do with the economy and more to do with innovation: coffee, fast-casual, quick-service (QSR), and delivery-only chains are simply doing a better job adapting to changing consumer preferences.

In Canada, the CDR segment hasn’t seen the kind of losses US restaurants have experienced. Over the past twenty years, Canadian FSRs have lost less than 2 percentage points to QSRs; American CDRs alone have lost more than that (2.5 percentage points) since 2014. In fact, Canadian FSRs grew slightly faster than QSRs in 2017.

Nevertheless, there are lessons to be gleaned from the sad state of the US CDR market. While restaurants like Applebee’s and Ruby Tuesday were pushing the same promotions, top LSRs — like Starbucks and Chipotle — were emphasizing what made them different. Two homegrown fast-casual restaurants in Canada, Mucho Burrito and Hero Certified Burgers, are using similar tactics.

Both the burrito shop and the burger grill emphasize the quality of their ingredients, something neither true fast-food joints nor CDRs tend to do. Mucho Burrito, which capitalized on Chipotle’s absence in Quebec, took “Real Food. Real Causes. Real People” as one of its slogans. And Hero Certified Burgers guarantees that all of its food comes from sustainable sources. These commitments set the two chains apart not only from competitors above and below them but also from competitors in the same segment.

The market in Canada may be concentrated among ten massive chains, but there’s still room for smaller brands and independents to claim market space by coming up with a big new idea.

2. Focus on Convenience Engineering

Another reason CDRs struggled over the last two decades is because they failed to keep up with the world around them. Technology is accelerating, and businesses that don’t pay attention are falling behind. This is the cautionary tale offered by Blockbuster: in 2008, then-CEO Jim Keyes said he didn’t consider Netflix competition. Three years later, the video-rental chain filed for bankruptcy.

Unlike Blockbuster, Domino’s Pizza has embraced new technologies. In FY ’15–’16, the company’s digital growth was 13.8x the size of its non-digital growth. By offering new ways to order (and receive) pizzas, from apps and text-ordering systems to more sci-fi concepts like drone delivery and autonomous vehicles, Domino’s has stayed on the cutting edge of technology to make it as easy as possible for consumers to buy from them.

Like Tim Hortons, Starbucks and McDonald’s have launched mobile apps, and, as of July 2017, 30% of Starbucks orders came from smartphones. McDonald’s is also installing self-service kiosks in all of its stores by the end of this year. These tech investments give customers new ways to order, making it easier than ever to purchase from these QSR giants.

Restaurants have been getting mobile another way: by investing in food trucks, the first big foodservice story of the twenty-first century. Food trucks are incredibly convenient for customers, which helps explain why 15% of the largest restaurant chains have gotten into the market.

Consumers like food trucks not only because they’re convenient but also because they diversify the food available near home or the office. Restauranteurs like them because they are relatively inexpensive, allowing them to experiment without investing in a brick-and-mortar storefront. The food hall — which offers small spaces for a number of restaurant concepts — likewise gives consumers extra convenience and new options as well as offering space for innovative new brands to take off.

Eataly will arrive in Toronto in 2019, but the city already has three excellent food halls: Assembly Chef’s Hall, Campo Food Hall, which offers markets as well as prepared food stalls, and the 25,000-square-foot Saks Food Hall.

Investing in food trucks and food halls would hit on the two fastest-growing segments in the Canadian foodservice industry: street food and fast food.

3. Focus on What You Do Best

Amazon’s forays in the grocery market may threaten the FAFH category’s recent gains. Between acquiring Whole Foods, launching a meal-kit delivery service, and opening Amazon Go (a grocery store with no cashiers), Amazon is trying to make buying groceries and cooking at home as easy as ordering a pizza from Domino’s or a latte from Starbucks. Canadian restaurants should be particularly wary, as FAH prices are consistently lower than FAFH prices — a trend that will likely intensify as the minimum wage increases go into effect over the next few years.

The fast pace of technological change often makes it feel like we’re in a brave new world, but the core values of the restaurant industry are the same. Offering a distinct and authentic brand, making ordering and delivery more convenient, and providing a variety of innovative concepts are just new ways of meeting customer needs. Restaurants may have new tools, but the task hasn’t changed: deliver excellent customer service visit after visit.