McDonald’s announced earlier this year that they’ve plugged their most gushing wounds through steps CEO Steve Easterbrook cites as “bold, urgent action.” It is true that U.S. same-store sales (sales for locations open at least 13 months) were up 5.7 percent in Q4 2015 and global sales increased five percent for the year’s last quarter, allowing McDonald’s to finish 2015 with a 1.5 percent increase.

But is this a result of the holistic turnaround so desperately needed by the company, or an effect of frantic emergency triage that cannot be sustained? Yes, an increase is an increase – but, let’s be honest, the added 1.5 percent is a silver lining won by selling off grandma’s jewelry with the start of all-day breakfast program and ill-advised discounting (the sign of a desperate, sinking ship). The October 6 launch of the all-day breakfast at McDonald’s gave the stock a significant boost, but same-store sales impact hasn’t been quite as strong.

SELLING GRANDMA’S SILVER ISN’T HELPING McD’S AUVs, BUT IT IS DRIVING THE STOCK PRICE

This much seems obvious to us, particularly when you look at the growth in the average unit volumes (AUVs) of Chick-fil-A and the decline in McDonald’s figures. Since 2010, Chick-fil-A’s AUV has been, on average, 17 percent higher than McDonald’s. And McDonald’s AUVs dropped about 7.6 percent from 2013 to 2014 (and continued to drop into 2015).

Almost certainly, one of the reasons (in our view) for falling McDonald’s AUVs is the sheer volume of menu items the company has added, having grown its menu size by 75 percent from the ten-year period of 2004 to 2014. This slowed down their operation by adding complexity, complication and confusion to both the franchisees/operators and the guests.

Worse still, it’s a glaring flaw that took eleven years and four CEOs for the company to identify. Earlier this year, Easterbrook laid out a plan to improve drive thru accuracy and reduce the size of McDonald’s drive thru menus, removing higher price items from the menu boards and emphasizing items with a $1.50 to $3 price tag. At first blush, we’re actually fans of this strategy – it’s one that should speed up drive thru times by focusing on simpler items that require less prep time in the kitchen. Faster service means greater throughput and, ultimately, a much needed sustainable sales increase. But it’s also a plan we’ll believe when we see it put in action – and, thus far, we (and other eager guests) haven’t seen much follow-through.

THE PARADOX OF CHOICE

Our analysis of more than a decade of drive thru and company performance yields some powerful, but perhaps at the same time rather obvious, findings. Namely, drive thru times have slowed significantly and menus have become over-complicated to the point where they exceed, in several instances, even full service restaurant menus. Why this is (and absolutely should be) so alarming for QSR operators is that it’s a reckless disregard for the core tenets of the business model (speed, convenience, accuracy, and simplicity).

Barry Schwartz’s 2004 book, The Paradox of Choice, is chock-full of case studies and lessons for all sorts of business operators – in particular, restaurant operators who have, in recent years, become addicted to the gains added from short-term menu items and LTOs. Under pressure to produce financial results and same-store sales growth, adopting the “everything to everyone” menu policy can seem like an attractive solution; but it’s one that quickly collapses under the unsustainable weight of menu obesity. Restaurant executives have allowed their menus to balloon out of control, and operators are finally waking up to the consequences of the addictions to the unsustainable gains achieved with over expansion of the menu.

We all think we want more choice, but as The Paradox of Choice evidences, it’s actually the opposite. In many ways, restaurant operators need to be freeing the guest of the tyranny of choice.

WANT A MENU SIMPLICITY CASE STUDY? LOOK AT CHIPOTLE

The Cheesecake Factory has 200 menu items, an anomaly in the industry. Across the board, restaurants have been migrating up in terms of number of items offered (word counts on several well-known casual dining menus are about five percent of the length of the average American novel) with several weighing in at 4,000+ words (requiring 14+ minutes to read in full).

In our view, certainly part of the success of Chipotle can be attributed to the simplicity of its menu and order format. The ingredients and combinations ultimately offer more variety and customization than all of the QSRs. With less than 50 words on the in-store menu boards, you can create more than 65,000 possible combinations (while the QSR menus average about 800 words with only 64 items). By comparison, McDonald’s drive thru menu has about 900 words and 86 menu items.

YOU’VE GOT THREE MINUTES AND 42 SECONDS TO GET IT RIGHT…

To read a menu of this size would take more time than the average person is willing to spend waiting in line at the drive thru. On average, the typical drive thru experience lasts just three minutes and 42 seconds – enough time for guests to pull up, select an item, place their order, pay and pull away with a meal.

Each new pre-sell board, promotional cling-on and attention-grabbing whirly-bird that they tack on to the menu boards serves a purpose – but eventually you get to the point where you look at the menu and can’t make heads or tails of it, and you end up (quite literally) pulling away.

It didn’t used to be this way at drive thrus. While apprehensive to sound like an old fogey who walked up hill both ways in the snow to get to school, I remember a time of much simpler drive thru menus. Not as stark as an Austin Power’s time warp, taking a break from QSR drive thru menus while working and living abroad, it’s overwhelming to come back and stare into the confusing abyss of a modern Taco Bell menu board. And they’re all just combinations of refried beans, ground beef and cheese, right?

… AND McDONALD’S ISN’T GETTING IT.

So who’s number one in drive thru? For three years running, it’s been Chick-fil-A (with Wendy’s also making some significant competitive strides, according to the QSR Drive-Thru Performance Study), based on speed of service, order accuracy and consumer sentiment.

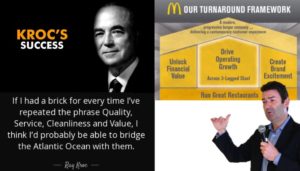

It seems blatantly obvious that the cure for McDonald’s woes is remembering what its visionary leader built the company on. Ray Kroc said “If I had a brick for every time I’ve repeated the phrase Quality, Service, Cleanliness and Value, I think I’d probably be able to bridge the Atlantic with them.” Getting back to these core values – quality, service, cleanliness and value – should be a focus for the company, not the “modern, progressive burger company” Steve Easterbrook has promised.

It’s estimated that Starbucks market capitalization will soon exceed that of McDonald’s, becoming the new most valuable foodservice company in the world. Starbucks has convenience engineering, really, at the core of its growth strategy both through mobile payment and a heavy concentration of new locations with drive thrus.

AN INCONVENIENT COMPARISON: STARBUCKS VS. McDONALD’S

Starbucks resisted for many years the notion of drive thrus and finally course corrected its own point of view. They had their first in 1994, then 171 by 2001 and opened 354 during 2004 alone. Today, Starbucks has a drive thru in about one third of its U.S. stores, and they account for 45 percent of the company’s total retail revenue.

By 2019, Starbucks expects to grow from $16 billion to $30 billion in revenue, with 60 percent of all new locations including a drive thru. Better still, these won’t be the static-plagued radio systems that were high-tech back in the 1970s, but video screens (already implemented at 2,400 U.S. Starbucks locations) that allow guests to actually see the associate taking their order. When coupled with several other innovations (digital/social/mobile payment, delivery programs, et cetera), this can be characterized as convenience engineering.

What’s McDonald’s grand plan for improving speed and order accuracy? An “ask, ask, tell” policy where after a customer places an order, the server immediately repeats the order back to them. The guest is then re-asked about order accuracy at the window during payment after the employee tells the guest exactly what is in the (not folded, but open to increase visibility) paper bag.

“These actions continue to show how we are changing and building a better McDonald’s,” McDonald’s spokesman Jeff Mochal told Bloomberg Business. Really? According to a New Jersey franchise owner, this time-consuming “no-tech” policy has only increased order accuracy by two percent. If 2013’s 88 percent accuracy estimates are used as a baseline, a two percent improvement still means that McDonald’s drive thrus still mess up the orders of one in every 10 customers.

OPPORTUNITY IS KNOCKING, BUT McDONALD’S ISN’T HOME

Improving the convenience engineering of drive thrus and take-out ordering is an area ripe for innovation, and not just incremental steps. As we like to say and remind our clients: one thing you can never do in business is make it too easy to buy from you. In other words, for drive thru operators, it is almost impossible to make it too fast or too convenient. Not to beat a dead horse, but, really, asking a guest about their order three times doesn’t hit the mark.

Convenience engineering is an area that’s dripping with opportunity for next-generation innovation – a buzzword that’s being thrown around at nearly every beleaguered restaurant chain. While they know they need to be doing it, in a lot of cases they’re looking for innovation and asking for the case study in the same breath. By it’s nature, true innovation does not have a predecessor of a case study for the faint of heart to draw courage from.

WHAT’S NEXT? YOUR GUESTS AREN’T (IMPATIENTLY) WAITING – THEY’RE GOING TO THE COMPETITION

As we’ve pointed out in previous posts, the leaders in restaurant point of sale systems don’t yet seem up to the challenge either of innovating or moving the industry forward as fast and frequently as Silicon Valley, yet Silicon Valley is ill-equipped (they don’t speak the language fluently) for connecting with restaurant operators. There is a significant opportunity to be had in bridging this gap, and we see this in many areas that have generated a lot of value, such as Yelp! and OpenTable.

It’s not whipping the horse harder or slinging more coal into the steam engine – it’s creating the automobile. We don’t anticipate there will be a hover-board lane any time soon, but we do suspect that tech (in its proper form) enables convenience. Why is it that you can order a pizza with an emoji but you still have to shout into a decades-old squawk box system to order at a QSR drive thru?

THE MULTI-BILLION-DOLLAR CATEGORY QSRs ARE OVERLOOKING

The bulk of the foodservice locations in the United States are fast food. And for the bulk of those, the majority of revenue comes from the drive thru. As menus are becoming more complex, drive thru times are slowing to a crawl. Start-ups and innovators in the industry (Postmates, UberEats and Amazon’s food delivery program, EAT24, to name a few) are going to be carving off a big piece of the pie.

There’s always going to be a need for drive thrus – people are always going to take road trips. But in urban markets, delivery is going to be a game changer. When you merge technology and convenience engineering together, you have the makings of a new multi-billion-dollar category. The company that realizes this will truly be capable of “bold, urgent action” – a sustainable business that reshapes everything we know about QSR foodservice while dated companies like McDonald’s are still applying battlefield band aids in an attempt to stop the hemorrhaging.