Restaurant mergers and acquisitions are having an influential impact on the global foodservice industry. Big companies are getting bigger and consolidating chains across categories, cuisines, and technologies. And regardless of the future economic climate, there will be an opportunity in the foodservice space. If there’s a liquidity crisis, M&A opportunities will come through consolidation and distressed assets investment. If the economy is booming, emerging brands and markets will reveal new growth acquisition targets and look to create footholds in new geographies (cross-border deals represent more than a third of global M&A activity).

While we expect M&A activity to continue to pick up over the next five years, there’s going to be a significant change in strategies. There’s plenty of capital to put behind foodservice companies, and some concepts that are not even on the radar right now will jump to very large valuations in the next few years — even a market for distressed assets.

We’ve seen this in other sectors — technology, in particular — where there’s been a huge uptick in the number of unicorns (privately held startups valued at more than $1 billion). The restaurant space saw its first unicorn in sweetgreen, and we anticipate a handful more over the coming years. Transformative technologies improving productivity in foodservice are likely to gain attention and investments as well.

Aaron Allen & Associates can help with every step of the M&A process, from target identification, valuation analysis, due diligence, value creation strategies, and integration plans.

Below, we’ve provided some additional insights about foodservice industry M&A.

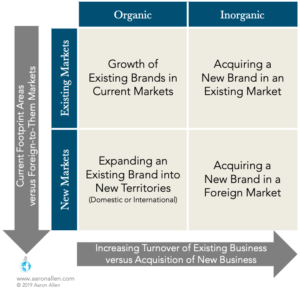

There is a spectrum of opportunities for restaurant acquisitions available for operators and investors alike.

Savvy investors can look at this time of uncertainty as an opportunity to broaden the landscape of potential attractive acquisitions. While some may be moving into this scenario opportunistically — smelling blood in the water — the most successful are realizing that this can be the perfect timing for a mutually advantageous acquisition to optimize portfolios and gain market share.

We are seeing a variety of opportunities across geographies, categories, cuisines, and phases of the business lifecycle. And just as hunters do not wait until they’re hungry to go out hunting, preparing for this flurry of investment activity ahead of it kicking off lays the foundation for a successful hunt.

The M&A fever is catching and burning white-hot from foodservice tech startups and corporate venture capital initiatives to budding emerging brands and the consolidation of mature and distressed brands around the world.

We think foodservice-related investments can be grouped into one of three types.

Some investors could be interested in all three buckets, or in certain angles of just one. There is going to be capital that wants to operate and knows how to integrate well into existing platforms, but there are others who need specialized expertise to manage a new system (that may even be in a different segment, category, or geography). The best data and advisors can help with each or all investment buckets and to propel organizations and investors forward.

M&A activity has ebbs and flows, especially in the foodservice space, but there is a trend for consolidation. Forward-looking executives are using mergers and acquisitions to fortify their operations: achieving top-line growth, consolidating market share, and adding necessary technological capabilities. The deals being made today will have a profound impact on the future of these organizations.

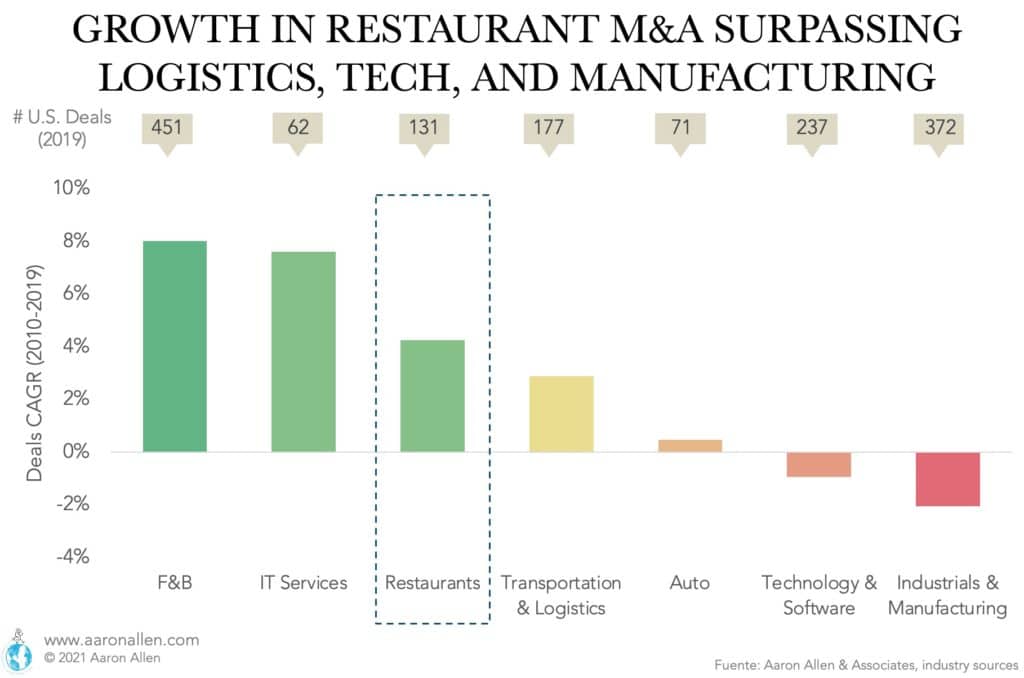

M&A activity across all sectors remains around $3.5 trillion globally (versus a peak of $4 trillion in 2018). Restaurants account for a small piece of this activity around the world — and it’s in the tens of billions for the U.S. foodservice market. Deals in the food and beverage industry grew at a 9.7% CAGR between 2010 and 2017, while the restaurant portion of that sector enjoyed 6.6% growth over the same period.

Emerging brands are studying incumbents and segment leaders for weaknesses to exploit — and some are, successfully. Those with size and scale are throwing their muscle and might into buying more muscle and might. Look no further than foodservice technology, where McDonald’s, Yum, and Starbucks have each made sizeable acquisitions over the past several years.

There are many explanations for this harried pace of M&A activity:

As interest rates rise and margins shrink, organic growth will become harder and harder to achieve in saturated categories and markets. Though restaurants have been gaining a steady share of stomach year-by-year in most geographies, the battle for the biggest piece of that share is escalating. In mature markets, the slugfest is brutal and unapologetic among existing restaurant chains all while grocery stores have started to fight back.

While industry growth is stable and steady, some sub-sectors and categories may be characterized by a sometimes-gruesome competition. In some environments, it’s more dangerous to stand still than to take calculated risks. Even frontier economies are quickly moving from fragmented to chain-dominated, and restaurants will have to do even more to stand out from their competitors and strengthen their systems with growth in size and scale.

This period of inexpensive capital and global opportunity is coming to an end, and leadership teams face a stark choice: execute a robust and aggressive acquisition plan to grow quickly or try to survive the squeeze against larger and/or more agile competitors that used this moment to lay the groundwork for a secure future. Acquisitions make strategic sense only if these moves are backed by solid due diligence and forward-looking strategy.

In the last two years Yum! Brands invested in Heartsyles, Kvantum, and (most recently) Tictuk Technologies. McDonald’s has done the same with Dynamic Yield and Apprente (2019). Starbucks made a $100 million commitment with Siren Ventures to invest in food and retail tech start-ups.

Foodservice technology is an arms race, moving so fast that not even the big guys have time to create technology — so they are buying proprietary tech by investing in these companies. The speed at which they are building these digital moats is astounding and creating an even broader divide between the “haves” and the “have nots”.

Now CEOs are waking up to the realization that their competitors jumped into the race cars pre-dawn and already have several hours of a head start. The investments by McDonald’s, Yum, and Starbucks all strike us as good uses of capital, but these companies only represent around 5% of the global foodservice industry.

We think the most valuable restaurant technology companies will ultimately be those that can serve the other 95%, particularly large enterprises.

With estimates projecting up to one-third of all restaurants permanently closing by end of 2020, corporate intelligence for the consumer, competition, technology, and disruptive forces is set to have an even higher ROI than usual.

Executive teams are wise to bring in quantitative data and objective analysis about what is happening both inside and outside the business. We deliver rich insights and industry intelligence to help inform corporate decision-making and strategy.

For mature brands, M&A offers expansion and consolidation opportunities. In the U.S., this is the case of many casual dining restaurants — 33% of pre-COVID deals (2018-2019) involved targets in the full-service category. In other cases, deals are often more focused on growth companies. This strategy has been successful for the fast-casual sector in the past and is increasingly starting to benefit the companies that have a “future of foodservice”™ angle to them — whether that’s technology, innovation and optimization in the front and back of the house, improved unit-economic model, or delivery companies (which have received a tremendous amount of capital investment over the last few years).

There are a variety of factors that influence mergers and acquisitions decisions, whether focused on mainly strategic or financial motivations. While these drivers for M&A are not necessarily new, understanding the evolving landscape helps to identify non-traditional value creation opportunities and a better assessment of risk.

Consolidation in sectors enables companies to gain market share which can then help from a management point of view and optimizing overhead. In other cases, investors put more of a focus on reducing costs. Next, we present some of the benefits motivating restaurant M&A.

When organic growth may be hard to come by, acquisitions can keep overall company revenue lines climbing steep slopes. An existing concept comes to its new owner with all its tangible and intangible value — from units and equipment to menus and brand — as well as its customer base with it. Combined, these new additions to the original portfolio accelerate revenue growth.

In 2018, revenue growth among publicly traded foodservice companies in the U.S. amounted to $8.1b (+7% year-over-year growth, from $122.1b to $130.3b). Inorganic growth (from acquisitions) was responsible for 28% of the increase. In the increasingly saturated U.S. market, inorganic growth will continue to have significant impacts for both private and public companies.

Consolidation is a major theme across foodservice, from the declining casual-dining segment to the booming delivery sector, and we expect this trend to accelerate. This strategy is especially useful for mid-sized firms hoping to increase their market share.

Example: In April 2018, rumors of a merger between DoorDash and Postmates began swirling. As of February 2018, Postmates controlled 9.1% of the U.S. delivery market while DoorDash claimed 13.9%. Their combined 21% would push them ahead of Uber Eats, which controlled 19.9%, and solidify their lead on Amazon (4.0% market share).

HelloFresh successfully completed a similar strategic acquisition when it bought Green Chef in March 2018. The purchase helped HelloFresh pass Blue Apron and become the largest meal-kit company in the U.S.

Acquisitions can be a means to penetrate foreign markets or new segments or categories “without doing the work” and spending time setting up a supply chain, establishing a location strategy, testing the new concept, etc.

Example: Amazon purchased the Middle Eastern e-commerce firm Souq in July 2017, giving the U.S.-based firm access to 45 million users in a region where online purchasing is growing at record speeds. E-commerce doubled between 2015 and 2017, and it is projected to post growth rates above 20% through 2021.

Amazon’s acquisition strategy also helps it gain a foothold in segments it has struggled to penetrate. Recognizing the growth of home delivery for groceries — 70% of shoppers are projected to buy at least some of their food online by 2025 — Amazon launched Amazon Fresh in March 2017. By November of that year, it had discontinued service in nine states, with some employees privately blaming the U.S. Postal Service. The acquisition of Whole Foods is giving Amazon another shot: with brick-and-mortar stores to serve as hubs and independent contractors working as drivers through the Amazon Flex program, the company is set up to claim a significant share of this new market.

Adding brands to a portfolio can bring new kinds of guests into a system’s orbit.

Example: Coca-Cola has been buying up and developing new beverage lines for almost two decades. From Odwalla (2001) to Honest Tea (2008) and coffee shop leader Costa Coffee (2018), the undisputed soda-champion is trying to reach more health-conscious customers.

These purchases, alongside the in-house development of brands like Dasani, give Coca-Cola an opportunity to sell to every consumer.

When Marriott International bought its former rival Starwood Hotels & Resorts in 2016, it acquired all Starwood properties — physical and intellectual. In the fourth quarter of 2016, Marriott reported a $42m increase to the bottom line and a 47% revenue improvement. In addition to the revenue and profit benefits Marriott reaped with the Starwood acquisition, it also got its 21-million-member-strong SPG loyalty program.

Foodservice is still undergoing seismic shifts and the pace of change is expected to continue — if not accelerate — in the coming years, sparked not only by even more transformative technological developments but also by the arrival of Gen Z, set to become the largest demographic group in the U.S. in 2019. Acquisitions can help companies keep pace with the evolving industry, and Starbucks’ handling of its Teavana acquisition is a key case study in this strategy.

Example: Since purchasing the tea company in 2012, Starbucks has integrated its products into its own units, building Teavana into a $1b brand. Where the parent company failed was in developing and nurturing standalone units: the real-estate strategy focused primarily on malls, which continue to suffer from declining traffic. In July 2018, Starbucks announced that it would close all 379 Teavana locations. Some were quick to classify this as another example of Starbucks’ spotty acquisition history, which includes Evolution Fresh juices and the La Boulange bakery.

But the company’s pivot from retail locations to grocery-store sales shows a canny understanding of market trends (and its solid understanding of corporate M&A strategies). Not only does the move rescue the brand from the graveyard of shopping malls, but it also gives Starbucks a new line of retail revenue, especially key after selling the rights to coffee sales in groceries to Nestle in May 2018.

As recently as 2009, some restaurant operations still saw their online presence as optional. At the NRA conference that year, Sally Smith of Buffalo Wild Wings said her organization would take a wait-and-see approach to social media. Such an attitude today feels incredibly outdated: the question isn’t whether to integrate technology, but how to do it. Acquisitions are a surefire way to add technology to an operation.

Example: As venture capital has increased in popularity over the past several years, corporations have also gotten in on the game. There are many merits to building a corporate venture capital (CVC) group, and it’s not just generating future financial returns. The right CVC investment can unlock new layers of growth, open channel expansion opportunities, or drive improved systemwide efficiencies through new technologies. Several foodservice companies have pursued CVC programs because of this, including Starbucks, Chipotle, and Yum Brands. Other foodservice companies like McDonald’s have been actively investing in technology startups the past several years, including the acquisition of Dynamic Yield (predictive analytics) and Apprente (voice recognition).

For multi-brand portfolios that want to add new concepts, acquisitions skip the development and proof of concept phase and go right to expansion.

Example: This strategy seems to motivate the massive MTY Food Group, which now controls over 70 brand names. In November 2017, it added two burger concepts, The Counter and Built Custom Burgers, to further expand its portfolio.

Other players in the food and beverage space are making similar moves. In May 2018, Kroger supermarkets spent $700m on Home Chef, a Chicago-based meal-kit company that already delivers 3 million meals to people’s homes every month. Home Chef will continue its original business while making its products available in Kroger grocery stores, allowing the chain to access the growing meal-kit sector, which is expected to have $10b in revenue in 2020.

By 2015, intangible assets, which include intellectual property and goodwill, accounted for a staggering 84% of the S&P 500’s value. This shows a 394% increase in 40 years. Globally, the most profitable businesses are those in the idea and knowledge economies, and value increasingly comes from brands and trademarks. Acquiring restaurant operations out of bankruptcy can revive still-valuable IP, adding its value the purchaser’s portfolio.

Example: In 2017, Landry’s won an auction for Joe’s Crab Shack and Brick House Tavern, spending just $57m for the two brands. With 95 locations open at the time, each unit cost Landry’s approximately $600k, a steal considering the concepts’ reported $3.1m AUV in 2013.

IP-focused acquisitions are also heating up the delivery space. In January 2018 Uber Eats bought New York-based start-up Ando; a company spokesperson explained that “Ando’s insights will help [Uber’s] restaurant technology team as we work with our restaurant partners to grow their business.” As delivery companies continue to consolidate, we’ll see more large platforms buying smaller competitors for access not only to their proprietary tech but also to the data they’ve collected on consumer behavior.

Large firms may make small acquisitions to consolidate market share, buy out competitors, or enter new markets. Many of the deals mentioned here qualify as bolt-on acquisitions, in which a smaller operation is integrated in a larger organization’s supply chain and distribution network. That’s the strategy General Mills is following as it adds brands like Annie’s Organic Foods, Larabar, and, most recently, Blue Buffalo Pet Products. The deals let General Mills enter the organic and healthful market and give the acquisitions access to many more retail outlets.

For this reason, lower middle-market leaders often look for a larger company to acquire them. As operations transition from emerging to emerged brands, they often find their capabilities — in human resources, marketing, supply chain, and governance — stretched their breaking point. They’ve gotten too big to keep staffing levels low and lean, but they’re still too small to completely fill out the corporate structure. Being bought out by a larger organization, with greater managerial capabilities, might be the safest way to grow.

Example: In the world of foodservice acquisitions, few firms have been as active — or as focused — as JAB. Since 2012, the German holding company has been building a coffee-and-bakery empire. Starting with Peet’s Coffee and Tea in 2012, JAB has bought up Keurig Green Mountain (2015), Krispy Kreme Doughnuts (2016), Panera Bread (2017), and most recently Pret a Manger (2018). Besides gaining market share in the café-bakery segment, JAB is also pushing competitors to make big moves of their own, as Nestle’s massive, $7b distribution deal with Starbucks demonstrates.

The deal between Krispy Kreme and Insomnia Cookies, announced in July 2018, is a perfect example. With over 1,000 locations globally, Krispy Kreme is more than five times the size of Insomnia, which has almost 200. Both organizations contribute unique capabilities to the deal: besides its standalone locations, Krispy Kreme sells its frankly perfect donuts in grocery and convenience stores, and Insomnia specializes in late-night delivery. More than that, Krispy Kreme, which has been in the business for more than 80 years, can help Insomnia move seamlessly out of the lower middle market as they transform from a start-up to a mature brand.

The deal between Krispy Kreme and Insomnia Cookies, announced in July 2018, is a perfect example. With 1,400 locations globally, Krispy Kreme is more than ten times the size of Insomnia, which has just 135. Both organizations contribute unique capabilities to the deal: besides its standalone locations, Krispy Kreme sells its frankly perfect donuts in grocery and convenience stores, and Insomnia specializes in late-night delivery. More than that, Krispy Kreme, which has been in the business for more than 80 years, can help Insomnia move seamlessly out of the lower middle market as they transform from a start-up to a mature brand.

This isn’t the easiest way to make money, of course: turning around a struggling restaurant concept, especially one in the casual-dining sector, is a task only the bravest in the industry are willing to take on. But the potential rewards match the challenge, with a successful turnaround creating ten- to twenty-fold returns on investment.

In March 2018, Spice Private Equity acquired Bravo Brio Restaurant Group for $100m. The last registered valuation for the company was 2.8x (EV/EBITDA) as of December 2017 — well below the industry median of 10.6x. These fire-sale prices offer the new owners an incredible opportunity to build value over the holding period. If Spice can bring Bravo Brio’s valuation up to just the industry median, without making any EBITDA improvements, it would result in a more-than-doubled enterprise value.

The history of Yum! Brands isn’t a story of strategic acquisitions; it’s actually a case study in smart, perfectly timed divestitures and spinoffs. Yum! Brands started as Pepsico’s fast-food division, which was spun off as Tricorn in 1997.

Restaurant M&A activity was white-hot from 2017-2019. However, the rise of investments in the foodservice industry had started long before. The number of restaurant M&A deals in the U.S. increased by 86% between 2004 and 2016.

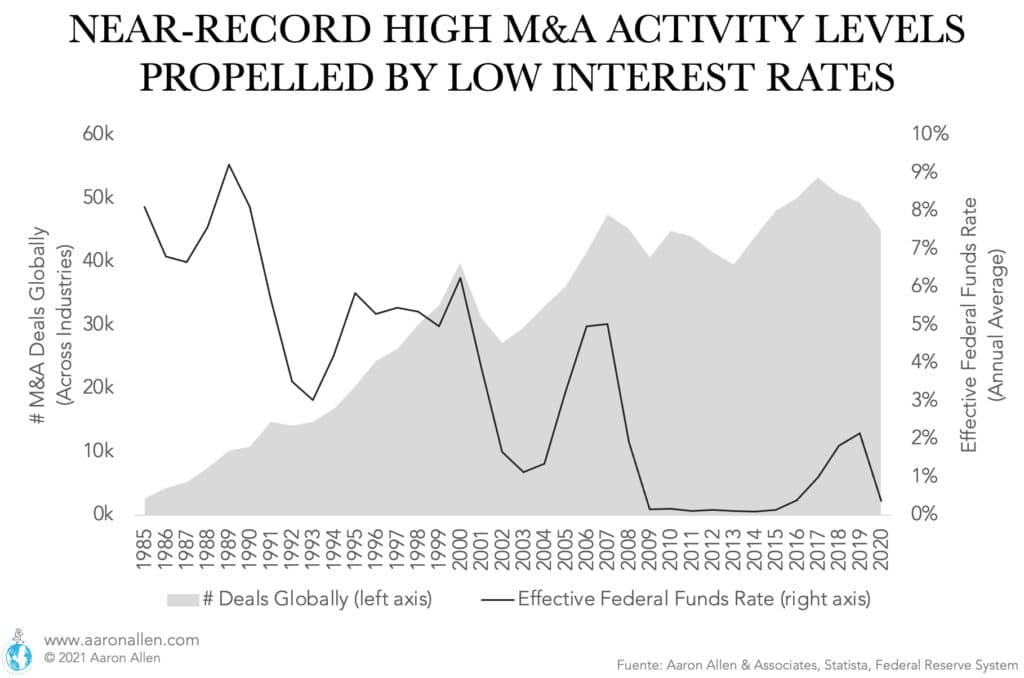

Initially, it looked like 2020 would be a down year for M&A activity in the foodservice industry due to hardships caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, but lower interest rates and ample dry powder (both corporate and strategic) drove a big recovery in deal activity during the second half of the year.

Below, we’ve included some takeaways from recent years’ M&A activity in the restaurant industry.

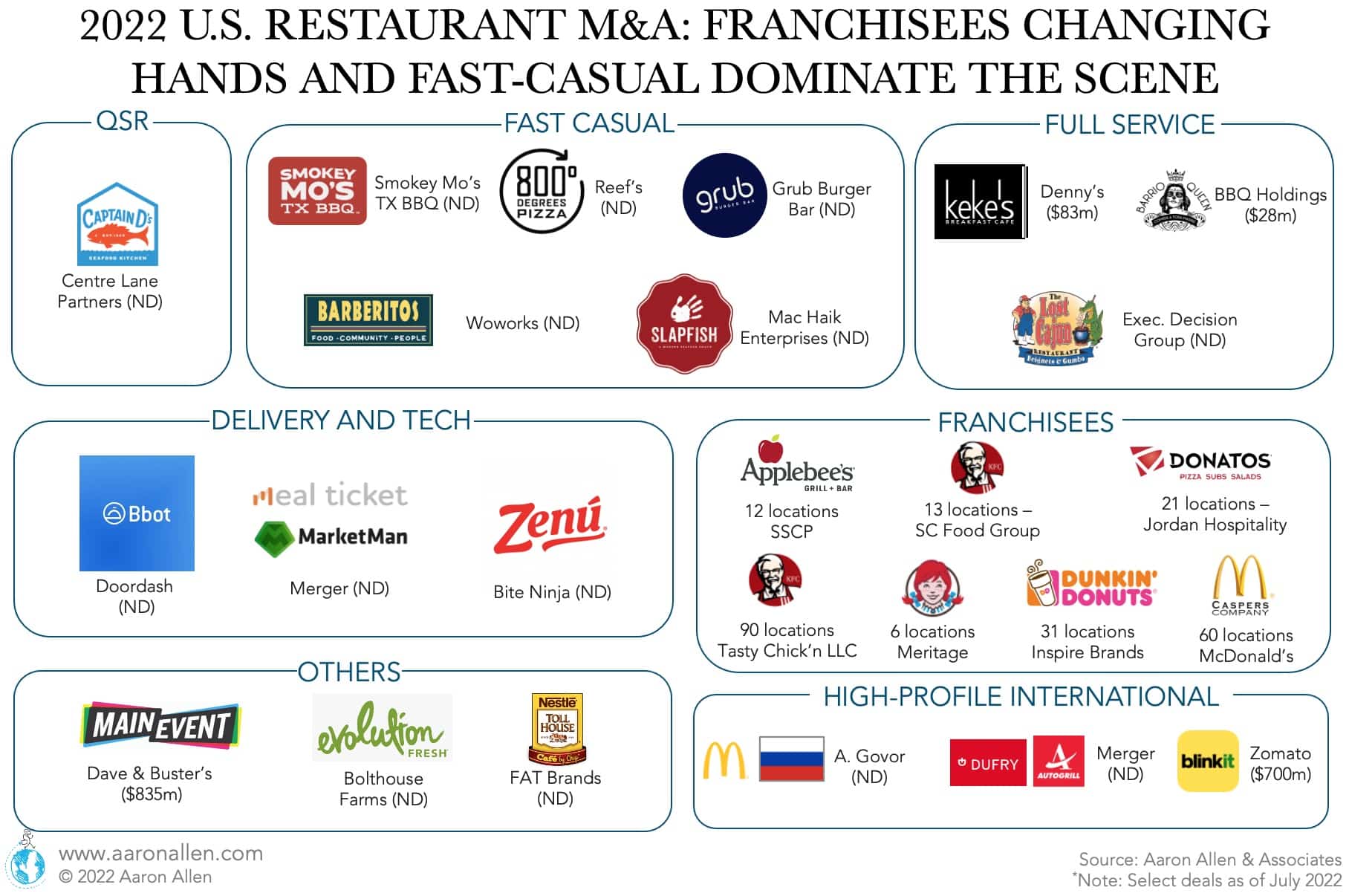

Though the foodservice M&A activity slowed down in 2022 compared to 2021, there were still plenty of deals happening. Firstly, a significant number of franchisees changed hands. Secondly, fast-casual was a very active segment (much more than QSR or full-service). Thirdly, there were several high-profile deals happening outside the U.S. (including McDonald’s Russia sale, Autogrill-Dufry merger in Europe, and BlinkIt merger with Zomato in India.)

Even with higher interest rates and a more challenging economic environment, private equity, venture capital, family offices, and institutional investors are getting deals done.

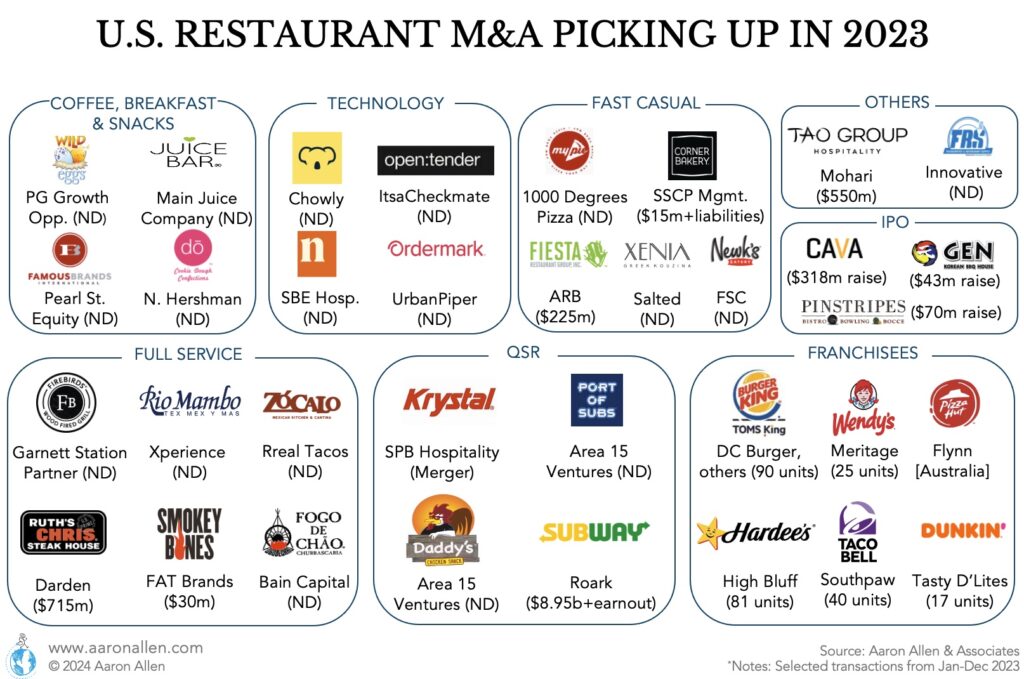

The M&A activity surged back in the restaurant industry in the U.S. in 2023. There were a number of acquisitions evenly distributed across segments, from snacks to fast casual to full-service and QSR. There was also a lot of activity among franchisees for QSR brands (including some bankruptcies).

There were a few significantly large transactions including the Subway acquisition by Roark Capital for $9 billion plus earnout and some debt, the acquisition of Tao Group for $550 million, and Darden acquiring Ruth’s Chris Steak House for $715 million.

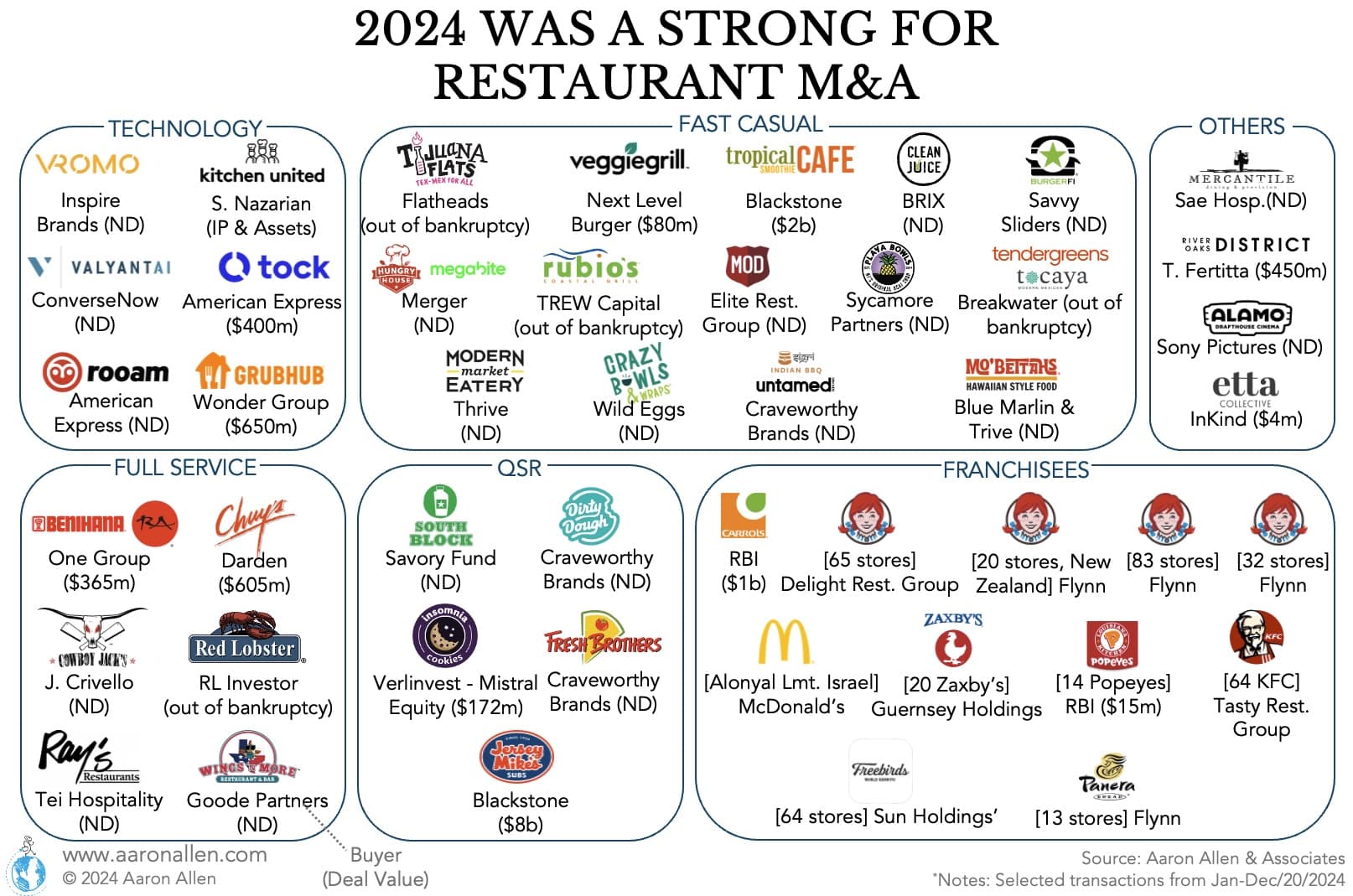

2024 saw a bounce back in restaurant M&A:

Inorganic growth is key in mature markets like the U.S. where growth only comes at someone else’s expense.

Plant-based fast casual chain Veggie Grill was acquired in January 2024 for $80 million (post-money valuation) by Next Level Burger & VegInvest. The restaurant chain had 27 locations at the time.

Inspire Brands, parent company to Arby’s, Baskin’ Robbin, Dunkin’, Sonic Drive Thru, Jimmy John’s, and Buffalo Wild Wings acquired Vromo for an undisclosed amount.

Tilman Fertitta (Landry’s owner) acquired River Oaks District for $450 million in March 2024. The target company is based in Houston, Texas.

Benihana and RA Sushi parent group Safflower Holdings was acquired in March 2024 by the One Group for $365 million.

Primary Aim sold 65 Wendy’s stores in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia to Delight Restaurant Group in April 2024. The deal value was not disclosed.

Alonyal Limited, Israel McDonald’s franchisee was acquired by the parent company. Alonyal was facing weak sales due to geopolitical conflicts in the region. At the time of the acquisition there were 225 McDonald’s stores in the country.

20 Zaxby’s restaurants franchised in South Carolina were acquired by Guernsey Holdings (currently franchises Sonic Drive-In and Little Caesars).

Tijuana Flats filed for Chapter 11 and was sold to Flatheads LLC. The fast-casual chain had 65 company-owned restaurants in Florida at the time of the deal and 26 franchised stores in Alabama, Florida, North Caroline and Tennessee. Terms of the deal were not disclosed.

Tropical Smoothie Café was acquired by Blackstone for $2 Billion in April 2024. The fast-casual chain had 1400 stores at the time of the deal.

The company had 75 restaurants at the time of the deal.

Tasty Restaurant Group acquired 64 KFCs in the central and Southeast of the U.S. from Triton Pacific Capital Partners.

Restaurant Brands International acquired Popeyes China, with 14 stores in Shanghai. The deal was valued at $15 million.

Valyant AI was acquired in July 2024 by ConverseNow. Valyant AI provides AI drive-thru ordering software and ConverseNow automates phone ordering with AI. Combined, the new company will serve more than 2,000 stores. Terms of the deal were not disclosed.

MOD Pizza was acquired by Elite Restaurant Group in a merger agreement. MOD was on the brink of bankruptcy and had 550 restaurants by 2023.

Darden Restautrants acquired Chuy’s for $605 million. At the time of the acquisition Chuy’s had 101 restaurants and $450 million in revenue.

Verlinvest and Mistral Equity Partners acquired a majority stake in Insomnia Cookies for $172.5 million in July 2024.

After declaring bankruptcy, Red Lobster was acquired for $375 million by RL Investor Holdings (a group of creditors).

American Express had previously acquired Resy. The company bought Tock for $400 million.

The Mexican food chain was sold to Lender TREW Capital Management in a $40 million credit bid in August 2024. Rubio’s had declared bankruptcy back in June.

Iconic franchisee Flynn Restaurant Group acquired 83 Wendy’s restaurants in August, 13 Panera restaurants in September, and 32 Wendy’s in November.

Another fast-casual chain was sold in 2024. Playa Bowls servers acai bowls and had 250 stores at the time of the deal.

After going bankrupt in March 2024, casual dining icon Red Lobster was acquired in September by a consortium of lenders, newly named RL Investor Holdings, for $375 million.

Fast-casual chain serving Hawaiian food was sold by Savory Fund to Blue Marlin Partners and Trive Capital. The current owners will retain a minority stake. In 2023, Mo’Bettahs had 50 restaurants and $80 million in revenue.

The California-based fast-casual chains were sold to the main lender Breakwater Management. The lender had provided $31 million in financing.

The fast-casual and casual dining chains were sold in a bankruptcy auction for $44 million. The buyer was the lender TREW Capital Management Private Credit 2 LLC.

Delivery company Grubhub had been bought in 2021 by JustEat Takeaway for $7.3 billion. In November 2024, the company was sold for $650 million to food ordering company Wonder Group.

Blackstone acquired the chain in November 2024. At the time, Jersey Mike’s had more than 3 thousand stores.

The brunch chain Wild Eggs, with 15 locations in Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio, was acquired by the investment group PG Growth Opportunities Fund (PGOF I). The deal, finalized in January 2023, aims to take the brand nationwide.

Restaurant technology company Chowly acquired Koala, a guest experience platform for restaurant brands. The partnership aims to provide advanced online ordering, data analytics, and machine learning recommendation engines to over 16,000 restaurant locations. Terms of the deal were not disclosed.

1000 Degrees Pizza, a 25-unit chain based in Galloway, N.J., acquired six-unit My Pie Pizza. Owner Amandeep Judge plans to use this as the first of several acquisitions. The company is also opening new locations in Florida, Maryland, and Pennsylvania.

New York-based investment firm Garnett Station Partners acquired North Carolina-based restaurant chain, Firebirds Wood Fired Grill, for an undisclosed amount. Firebirds has 56 locations across 20 states.

Xperience Restaurant Group, the parent company of Chevys Fresh Mex and Sol Mexican Cocina, acquired Rio Mambo Tex Mex y Mas and The Rim Scratch Craft Eats from RM Restaurant Group. With this acquisition, Xperience Restaurant Group adds six units to its portfolio of 68 restaurants, and plans to expand further with new Sol Mexican Cocina locations in New York City and Boston.

New York-based Mighty Quinn’s Barbeque made a strategic investment in Detroit-based Slows Bar BQ. The acquisition will expand Mighty Quinn’s footprint into the Michigan market. Both brands will continue to operate independently under a new holding company. Mighty Quinn’s aims to reach at least 100 units in the future. Terms of the deal were not disclosed.

Main Squeeze Juice Company, a 28-unit juice bar and smoothie chain, acquired I Love Juice Bar, a 23-unit brand based in Tennessee and Texas for an undisclosed amount. The two brands will merge under Main Squeeze Juice Co., keeping a plant-based, health-forward menu.

Flyby Robotics, a drone automation and delivery company, raised $4 million in seed funding led by Mac Venture Capital. The funding will support technical development and expansion of pilot programs across the US.

QSR Krystal Restaurants and SPB Hospitality (parent to Logan’s Roadhouse, Old Chicago Pizza, and J. Alexander’s) completed the merger in April 2023.

Mubadala Investment Co. is acquiring a majority stake in Fortress Investment Group — SPB Hospitality’s owner.

Mohari Hospitality, an investment firm, plans to acquire Tao Group Hospitality from Madison Garden Entertainment Corp. The deal, valued at $550 million, is set to close in May 2023. With this acquisition, Mohari will own Tao Group alongside co-CEOs Noah Tepperberg and Jason Strauss.

Tao Group has a portfolio of 80 restaurants including TAO, Hakkasan, OMNIA, LAVO, and others.

Area 15 Ventures, a private-equity firm based in Colorado acquired Port of Subs, a 50-year-old sandwich chain with 130 restaurants across seven Western states. The deal was finalized in March. The PE firm also acquired Daddy’s Chicken Shack (with 160 units in development).

Foodservice & Restaurant Supply (FRS) was acquired by the Innovative Foodservice Group (IFG). FRS has four locations. Terms of the deal were not disclosed.

SPB Hospitality (with a portfolio including Logan’s Roadhouse and Old Chicago) completed the merger with fast food chain Krystal Restaurants. Each brand in SPB’s portfolio will continue to operate independently. Fortress Investment Group now owns both Krystal and SPB Hospitality.

Meritage Hospitality Group acquired 25 Wendy’s restaurants in May. The company has a 5-year growth plan to operate up to 400 Wendy’s locations. The acquisition was funded through a combination of cash, equity, and financing, and is expected to add approximately $42 million in annual sales. Meritage also has 52 new Wendy’s restaurants in the pipeline by 2025 and continues its expansion in other brands, including Taco John’s and Morning Belle.

Darden Restaurants — the publicly traded parent company of Olive Garden and LongHorn Steakhouse, completed a $715 million acquisition of Ruth’s Hospitality Group. With this deal, Darden adds 155 fine-dining restaurants to its portfolio.

Flynn Restaurant Group, the world’s largest franchise operator, made its first international deal by acquiring Pizza Hut Australia. The franchisee has 260 which will be added to Flynn’s 945 U.S. Pizza Huts. Terms of the deal were not disclosed.

Sam Nazarian (SBE Hospitality Group’s CEO) acquired Nextbite, including its virtual brands, shortly after selling off Nextbite’s order management arm, Ordermark. Nextbite’s virtual brands will continue under SBE as “Nextbite by SBE,” operating separately from C3’s virtual brands.

In the wake of Nextbite’s third round of layoffs, Indian software company UrbanPiper purchased the U.S. business segment of Ordermark, a virtual restaurant company’s online order management platform. Ordermark was founded in 2017 and provides software solutions for restaurants to manage online orders. Details of the sale were not disclosed.

Four Corners Property Trust (FCPT) finalized the purchase of 13 corporate-operated Darden restaurant properties for $79.5 million: 12 Cheddar’s Scratch Kitchen locations and one Olive Garden property. The company’s portfolio encompasses 71 properties, with annualized in-place rents reaching approximately $213 million.

Fast-food franchisee Southpaw acquired nearly 40 Taco Bell restaurants in the Atlanta market. Southpaw now operates 115 Taco Bell restaurants and 65 Dunkin’ locations, across eight states with an annual revenue of $300 million.

Publicly traded Fat Brands is planning to take one of its brands, casual dining Twin Peaks, public. While Fat Brands will remain the majority owner of the 100-unit chain, the spinoff is supposed to create value for shareholders. Twin Peaks was acquired by Fat Brands in 2021 for $300 million.

High Bluff Capital Partners, the parent company to Quiznos, Taco Del Mar, and Church’s Texas Chicken, plans to purchase 81 Hardee’s locations following the bankruptcy of Summit Restaurant Holdings.

Fast-casual restaurant chain Cava made an Initial Public Offering in June. During the first day of trading the company shares value almost doubled. Cava has more than 260 restaurants and the IPO raised $318 million at an enterprise value of $2.45 billion.

Casual-dining restaurant chain Gen Korean BBQ parent company raised more than $43 million in its NASDAQ IPO at the end of June 2023.

Sold by Sun Capital Partners, the purchase is expected to increase annual adjusted EBITDA by approximately $10 million and add 61 new restaurant locations to FAT Brands’ restaurant portfolio.

The parent company of the Pollo Tropical chain was acquired for $8.50 per share, making the company private. The acquisition is expected to amplify the core aspects of the Pollo Tropical brand and expand its capabilities.

The company was valued at around $1.1 billion. The acquisition was completed in August 2023 and the new ownership plans to accelerate Fogo de Chão’s expansion to an annual growth rate of 15%.

The parent company of Ms. Fields and TCBY was sold for an undisclosed sum. The acquisition is expected to improve franchise support and support the international growth of both brands.

The acquisition was announced on December 12, 2023 and financial details were not disclosed.

The virtual restaurant company announced a $14 million Series B fundraising round together with the acquisition of Xenia.

Newk’s Eatery was a 100-unit fast-casual restaurant chain at the moment of the sale. The transaction was completed for an undisclosed amount.

Tasty D’Lites now owns 37 Dunkin’ restaurants in Vermont and North Carolina.

The eatertainment restaurant chain announced is exploring a sale. The company is working with investment bank Goldman Sachs on an auction process to attract private equity firms.

The QSR dessert company was sold at the beginning of 2023, specifics of the deal were not disclosed.

The Restaurant Group (owner of Wagamama) was acquired by £700 million by Apollo Global Management.

In September 2023, Subway (the largest fast food chain by number of stores) was acquired by Roark Capital for $9.55 billion, including debt, with an earn-out. The company had been running an auction process since the beginning of the year.

Center Partners bought Captain D’s from Sentinel Capital Partners in May 2022. The terms of the agreement were not disclosed. The brand has 536 restaurants.

Alexander Govor will acquired the entire portfolio of McDonald’s in Russia for 1.4 million. He agreed to keep all employees on the payroll for 2 years.

The Lost Cajun after having gone bankrupt, the company has been acquired by Executive Decisions Group Inc. (EDGI). The financial terms of the contract were not disclosed.

Autogrill and Dufry plan to merge, to become the world leader in travel retail.

Dave & Buster’s announced it intends to buy the food and gaming chain Main Event for $835 million.

Zomato and Blinkit agreed to merge, valuing all Blinkit shares between $700 million and $750 million.

Publicly traded J. Alexander’s Holdings (including the concepts J. Alexander’s, Redlands Grill, and Stoney River Steakhouse and Grill) are to be acquired by SPB Hospitality for $220 million (pending shareholders approval). The company has $4.66 million in EBITDA, putting valuation at an impressive 47x EV/EBITDA.

Fiesta Restaurant Group sold Taco Cabana to Jack in the Box’s largest franchisee, Yadav Enterprises.

Ampex Brand, a Yum! Brands franchisee, acquired the fast-casual chain from Panera Bread (owned by JAB Holdings) for an undisclosed amount.

The multi-concept group (including brands such as Round Table Pizza, Great American Cookies, Hot Dog on a Stick, Marble Slab Creamery, and Pretzelmaker) is set to be acquired by FAT Brands for $442.5 million.

In June 2021 Famous Dave’s parent company announced the acquisition of family dining chains Village Inn and Bakers Square for $13.5 million after the chains emerged from bankruptcy.

Terms of the deal were not disclosed. The QSR franchisor is set to be acquired by Artemis Lane Partners.

Luby’s cafeteria business was sold to an affiliate of entrepreneur Calvin Gin for $28.7 million.

The fast-casual chain has 92 units. It was acquired by Black Titan Enterprises from former owner Luby’s.

The coffee and doughnut chain was sold for an undisclosed amount in early 2021. It had been family owned since 1936.

The valuation was not disclosed. Capprioti’s is planning to grow Wing Zone top line by leveraging technology.

Mighty Fine Burgers Fries & Shakes was acquired by Tc4 & Co. Hospitality with the goal of expanding this concept into other cities in the state.

Bankrupted NPC International sold its Pizza Hut and part of its Wendy’s locations to Flynn. The remainder Wendy’s locations were sold to Wendy’s parent company. The transactions were worth about $800 million combined.

In February 2021 it was announced the merger between Landry’s, the Golden Nugget and blank check company Fast. The deal would be worth $6.6 billion.

Uber acquired the alcohol delivery company Drizly for $1.1 billion.

The PE firm bought the fast-casual steakburger chain for an undisclosed amount.

In March 2021, Yum! Brands announced the acquisition of AI company Kvantum and TikTuk Technologies (fast food ordering via text and social media). In May the acquisition of Dragontail Systems (restaurant workflow management systems) for more than $90 million.

Local delivery company Waitr was acquired by Delivery Dudes. Terms of the deal were not disclosed.

The deal for the salad making robotics start-up was announced in February 2021.

The parent company BC Hospitality Group had filed for bankruptcy due to COVID closures.

D&G Investors acquired the 300-unit pizza chain out of bankruptcy after acquiring $81.6 million of Cici’s debt.

The private equity firm had a minority stake in the Middle Eastern fast-casual chain.

Chipotle acquired a minority stake in self-driving vehicles company Nuro.

The acquisition of the loyalty platform was valued at $500 million.

Terms of the deal were not disclosed.

Bakery chain Nothing Bundt Cakes was sold in May 2021 to the private equity group Roark. Levine Leichtman Capital Partners was the previous owner.

Next Level Hospitality has been acquired by Aramark where it will operate as a separate division under its own brand within Aramark’s healthcare business.

Playa Bowls received a majority investment from Tamarix Equity Partners and Pacific General Holdings. The company is now at the 120+ unit mark and was valued at $65 million.

Mastercard (MA) has agreed to acquire McDonald’s state-of-the-art personalization platform and decision engine (MCD) business, Dynamic Yield. Terms of the deal were not disclosed.

In November, Sun Holdings Inc. acquired 131 Applebee’s restaurants (across 14 states) previously in the hands of RMH Franchise.

In December Jack in the Box agreed to buy Del Taco for $575 million. The deal represents valuation multiple of 7.6x TTM EBITDA.

Restaurant Brands International purchased the subs chain Firehouse Subs for $1 billion in cash.

FAT Brands acquired Fazoli’s from Sentinel Capital Partners for $130 million.

At the end of 2021, Olo made its first acquisition. The target was the software solutions company, Wisely, valued at $187 millions.

BurgerFi has agreed to purchase 61-unit Anthony’s Coal Fired Pizza & Wings from L Catterton for $161.3 million in assumed stock and debt.

FAT Brands acquired casual dining Twin Peaks from Garnett Station Partners for $300 million.

Private equity firm FFL Partners sold Church’s Chicken (1,500 restaurants) to High Bluff Capital Partners.

The deal was announced in January 2020. The fast-casual burger chain was valued at $375 million. Yum! also acquired the UK-based leadership development company Heartsyles this year.

The deal was financed by L Catterton.

The ghost kitchen operator Zuul acquired online restaurant ordering Ontray for an undisclosed amount.

BBQ Holdings gained two concepts with the purchase.

The deal for the 3-unit operator was valued at $7.5 million.

Cornog and R. Flaherty acquired an 80% stake.

The rotisserie chicken concept was sold for an undisclosed amount.

The burger chain was sold out of bankruptcy for $27 million, with $21.5 million in debt, in May 2020.

The food delivery company Grubhub was acquired by Just Eat/Takeaway for $7.3 billion.

The deal took place in November 2020 for $2.65 billion.

The fast-casual pizza chain acquired 13 franchised units in North Carolina form SD Holdings.

Johnny Rockets has 325 restaurants (most of them franchised). The deal was valued at $25 million.

Golden Gate Capital had purchased Red Lobster from Darden 2014 for $2.1 billion.

Management participated in the deal.

The restaurant and golf concept merged with Callaway (golf products producer) officially in 2021, though the deal was announced in 2020.

The fast-casual brand was acquired for an undisclosed amount.

Taking Dunkin’ private was Inspire’s biggest deal to-date.

PPX Hospitality Brands acquired Boston-based Legal Seafoods. PPX is also the parent to Smith & Wollensky and Strega.

Amici Partners Group acquired the family-dining chain’s assets.

Thompson Hospitality bought Matchbox’s assets.

The restaurant technology company was sold to Lightspeed POS.

In January 2019 Centerbridge sold the casual-dining chain.

QSR franchisee Carrols acquired 165 Burger King and 55 Popeyes restaurants from Cambridge Franchise Holdings in ten Southern and Southeastern states. The deal was valued at $238 million.

The new health-focused group is called Modern Restaurant Concepts.

In March 2019 McDonald’s announced the acquisition of Dynamic Yield with the aim of use the company’s technology to personalize drive-thru menu boards, kiosks, and mobile ordering. In September 2019 McDonald’s acquired voice-based technology company Apprente.

The Canadian group acquired the pizza chain for $190 million.

The PE firm was the previous owner of Dave & Buster’s.

The deal was valued at $650 million.

The deal was valued at $10 million.

Performance Food Group acquired Reinhart in a $2 billion deal.

Nord Bay Capital and TriArtisan Capital Advisors are the company’s new owners.

In mid-2019 this was one of the deals showing the increasing consolidation in the foodservice technology sector.

The deal was valued at around $700 million.

Continuing its cross-border activity, Jollibee acquired the coffee chain for $350 million.

The casual-dining chain acquired the incubator Fox Restaurant Concepts for $353 million and the remaining interest in North Italian for $130 million.

The deal was valued at $450 million.

The founding family of the burger chain will keep a minority interest.

The fast-casual Asian restaurant was sold by Centerbridge.

The deal took place in May 2019.

The operator of the STK steakhouse chain bought Kona Grill’s 24 restaurants and other assets for $25 million in cash and $11 million of Kona’s liabilities.

Landry’s chose the best locations of Restaurants Unlimited and acquired assets for $37.2 million.

Huddle House agreed to buy the rights to Perkins Restaurant & Bakery for $51.5 million.

The fast casual chain acquired delivery service Galley Foods.

The valuation for the sandwich chain was not disclosed.

The PE firm L Catterton was the previous owner.

The deal was valued at $36 million.

The chain was valued at $18 million.

The deal to take the casual dining chain public via a SPAC failed. It would have valued the company at $380 million.

The Buffalo Wild Wings franchisee was acquired by ICV Partners in November 2019.

Switzerland-based Nestlé announced it was buying the rights to market Starbucks retail products, including beans and capsules, for $7.2 billion.

In December of 2018, Inspire Brands announced the completion of its acquisition of Sonic for $2.3 billion. The deal brought Inspire’s portfolio to more than 8,300 locations and generating systemwide sales of $12 billion.

JAB was on a buying spree. In addition to the UK-based (with U.S. operations as well) Pret A Manger acquisition, it also acquired Insomnia Cookies (via JAB subsidiary Krispy Kreme) in July 2018. JAB also added Core Nutrition, a bottled water company, thanks to a purchase by Keurig Dr Pepper. JAB’s dominance in the beverage sector may have prompted Coca-Cola’s $5b+ purchase of Costa Coffee, a U.K.-based café chain with 3,000+ locations worldwide. The acquisition not only gives the soda company entry into the fast-growing coffee category, but it also provides essential brick-and-mortar locations that will get more Coke products in front of more consumers.

In all-cash transaction, Durational Capital Management and The Jordan Company acquired Bojangles’ Famous Chicken ‘n Biscuits for $16.10 per share. The company had 764 restaurants throughout the southeast U.S. at the time of the acquisition.

Grocery chain Kroger made a $700 million acquisition of meal-kit company Home Chef. Kroger planned to offer individual meal kits in its vast empire of supermarkets, beyond the existing subscription/delivery business of Home Chef.

After making an IPO in 2015, Brazilian steakhouse chain Fogo de Chão was taken private by Rhone Capital for $560 million. While the chain has strong average unit volumes, high average check, and solid profit margins, it had failed to build stock prices since going public.

The struggling Tilted Kilt (one of the “breastaurant” players) was acquired by the ARC group, which founded Dick’s Wings & Grill, in June. Shortly thereafter in August, it also announced the acquisition of four-unit casual-dining chain Fat Patty’s.

In April of 2018, Los Angeles–based Elite announced its acquisition of Daphne’s, a Mediterranean concept with 23 units in California. It quickly shortened the name, updated the menu, and launched remodels. In August, Elite purchased Patxi’s Pizza.

Sinelli Concepts, based out of Dallas, added the 45-unit gelato concept Paciugo to its 438-unit Which Wich brand. Sinelli also owns Burguesa Burger, with two units, and will debut its new concept, Supernova Coffee, by the end of 2018.

With almost 75 brands, MTY Food Group is a major force in North American foodservice. Specializing in franchised concepts with units in malls, movie theaters, and convenience stores, the concepts in MTY’s portfolio have over 5,000 locations ranging from Chinese and Japanese cuisine to burgers, sandwiches, and snacks. With its acquisition of self-serve frozen yogurt concept sweetFrog, the company added almost 300 units, most of which are in the U.S.

Del Frisco’s purchase of Barteca gives it Bartaco, a more casual concept that will complement its higher-priced eateries without sacrificing service or quality. These initiatives highlight casual dining’s unique place in the restaurant landscape rather than trying to imitate the success of faster and cheaper options.

Almost exactly a month after High Bluff Capital Partners announced its purchase of Quiznos’ parent company QCE LLC, it acquired Taco Del Mar: more evidence that the middle market is steaming. While Quiznos has been struggling for years, and High Bluff hopes to stage a turnaround, the investment in Taco Del Mar is designed to fuel the fast-casual chain’s expansion efforts.

Landcadia, which owns and operates Landry’s Seafood, Bubba Gump Shrimp, Morton’s The Steakhouse, and over three dozen more restaurant and hotel brands, purchased Waitr, a delivery platform that services more than 5,000 restaurants in markets all over the Southeast.

Golden Tree, the parent company of quick-service restaurant (QSR) fried-chicken chain Golden Chick, purchased Texas-based Fireside Pies

An independent Atlanta investor group acquired popular Atlanta sports bar chain, Taco Mac.

While financial terms of teh deal were not disclosed, Sentinel Capital Partners announced the sale of the 349-unit chain Huddle House, which generated more than $240 million in system-wide sales.

Bravo Brio, which owns Bravo! Cucina Italiana, Bon Vie Bistro, Brio Tuscan Grille, and Brio Coastal Bar & Kitchen, has suffered the fate of many casual-dining restaurants: declining sales and dwindling locations.

Foodservice-centric investment firm, TriSpan, acquired polished casual chain Rosa Mexicano from Goode Partners.

UberEats purchased Ando, the delivery-only concept from celebrity chef David Chang. Chang hoped to find solutions to all the various challenges food faces between the kitchen and the customer’s front door but got bogged down in the incredibly complex logistics and technical requirements. It often used Uber Eats to deliver its food, only hiring its own delivery staff for core clientele. Ando ceased operations the day after the deal was announced.

Square, Caviar’s parent company, bought certain assets of Dallas-Fort Worth–based Entrees On-Trays. The acquisition is a nice match, as both Caviar and Entrees On-Trays specialize in delivering meals from local restaurants.

HelloFresh bought up meal-kit competitor Green Chef, which specializes in organic ingredients, vegan and gluten-free options, and meals that fit in with Paleo and Keto diets. This nicely expands HelloFresh’s offerings.

SJB Brands purchased Jamba Juice–competitor Juice It Up, which has recently expanded its beverage offerings to include cold-pressed organic and raw juices

Grabbagreen, a QSR concept that replaced supersized value meals with superfood bowls and wraps, was purchased by Canadian franchisor MTY Food Group, which also owns Blimpie, Cold Stone Creamery, and Pinkberry.

Butterfly, a specialized restaurant private equity firm, bought Modern Market, which has locations in Arizona, Colorado, Maryland, Texas, and Washington, DC. Modern Market makes farm-to-table accessible to more people by offering sustainable ingredients in a quick-service environment.

Perhaps the biggest 2017 restaurant merger or acquisition deal (at least so far) was the September announcement that Post Holding Inc. (maker of Honey Bunches of Oats and Grape-Nuts cereals), would buy Bob Evans Farms for roughly $1.5 billion. After activist investor Thomas Sandell began pushing for change, Bob Evans announced it would split the company in 2017, when it sold its 522 Bob Evans restaurants to private-equity firm Golden Gate Capital in a $565 million deal in May. The chain was then taken private as Bob Evans Restaurants.

Global Franchise Group, the parent company of Great American Cookies, acquired the 450-unit Round Table Pizza chain for an undisclosed amount in September 2017. The acquisition of the pizza company gives the Atlanta-based Global Franchise Group a portfolio of brands in operation of more than 1,500 locations and nearly $1 billion in combined system sales. GFG also owns Pretzelmaker, Hot Dog on a Stick and Marble Slab Creamery/Maggie Moo’s Ice Cream.

While rumors swirled that that Panera might be acquired by one of its peers in the restaurant industry (like Domino’s, Restaurant Brands International, or Starbucks), the bakery and cafe chain eventually found a new parent in JAB in a $7.5 billion deal completed in July 2017. JAB, a German-based conglomerate, has also acquired Krispy Kreme, Keurig, and Peet’s Coffee & Tea.

Restaurant Brands International made headlines in 2017, when it announced it would acquire Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen for $1.8 billion in cash. The company is expected to use its international reach to bring Popeyes’ to new geographies around the globe. Restaurant Brands was formed in 2014, through an $11 billion merger between Burger King and Canadian chain Tim Hortons).

In July, Starbucks announced it had entered into a definitive agreement to acquire the remaining 50% share of its East China business from long-term joint venture partners, Uni-President Enterprises Corporation and President Chain Store Corporation, a deal valued at approximately $1.3 billion in cash consideration (and the largest single acquisition in the company’s history). The acquisitions builds on the company’s ongoing investments in China, its fastest-growing market outside of the United States in terms of store count.

Nestlé bought into the third-wave coffee buzz with its September acquisition of a 68% stake in Blue Bottle Coffee, an Oakland-California-based purveyor of high-end coffee. According to a press release, Blue Bottle Coffee will continue to operate as a stand-alone entity. Other terms of the deal were not disclosed. Currently, Blue Bottle has about 40 cafés in New York, San Francisco and other metropolitan cities, with that number expected to reach 55 by year’s end. The acquisition will make Blue Bottle the latest coffee chain in Nestlé’s cadre of brands, which also includes Nescafe and Nespresso. Nestlé’s been snapping up other food brands, too — earlier this year it purchased vegetarian packaged foods company Sweet Earth, and also invested in meal kit company Freshly.

In March 2017, Darden Restaurants agreed to a buy Cheddar’s Scratch Kitchen for $780 million from a group of stockholders including private equity firms L Catterton and Oak Investment Partners. Cheddar’s currently has 165 locations, including 140 owned and 25 franchised, in 28 states, though Darden has noted the chain has “significant growth opportunities in new and existing markets” and average annual restaurant volumes of $4.4 million.

In May, Chicago accelerator Cleveland Avenue LLC (founded by former McDonald’s CEO Don Thompson) acquired a majority stake in the fast-casual pizza chain PizzaRev. The fast-casual pizza chain grew quickly after a 2003 investment by Buffalo Wild Wings. PizzaRev and currently has more than 50 locations, with 200 more under development.

In March 2017, private equity firm Oak Hill Capital Partners announced plans to buy the Tampa-based Checker’s fast-food chain from its equity ownership for roughly $525 million.

Fidelity National Financial Ventures, the parent of Ninety Nine Restaurant & Pub, a 106-restaurant chain, announced in August that it would merge with J. Alexander’s Holdings in a $199 million deal. J. Alexander’s operates four concepts including 19 eponymous locations, as well as Redlands Grill and Stony River, each with 12 units. The 65-year-old Ninety Nine, a casual dining chain, reportedly had more than $300 million in revenue in 2016.

In September, Fatburger parent FAT Brands, which recently announced plans to go public, paid $10.5 million to acquire Homestyle Dining, owner of the Ponderosa and Bonanza steakhouse chains. The acquisition includes ambitious plans for international franchising, as well as the development of a fast-casual version of Ponderosa.

In January, Argosy Private Equity and MTN Capital Partners took a controlling stake in Italian ice chain Rita’s, which has more than 600 units in the US, and is working to expand internationally in the Philippines, Canada and the Middle East. Terms of the deal were not disclosed.

Caribou Coffee announced plans to acquire Bruegger’s Bagels in August. Caribou’s parent, JAB Holding Co., is the owner of a growing portfolio of restaurant brands including Panera Bread, Krispy Kreme Doughnuts and Einstein Bagels. The 269-unit Bruegger’s was acquired for an undisclosed amount.

SBE, a privately held hospitality company that operates hotels, restaurants and nightclubs around the world, announced in March that it was in “advanced discussions to merge Hakkasan Group into the SBE family.” Founded in 2002, SBE manages 23 hotels and residences in nine markets and many more entertainment and food and beverage outlets, including Bazaar Meat, Cleo, Umami Burger and Katsuya restaurants at SLS Las Vegas; Double Barrel Roadhouse at Monte Carlo; and Hyde nightclub and lounge at Bellagio and T-Mobile Arena.

In a deal meant to propel expansion, San Francisco fast-casual restaurant Tava Kitchen was acquired by Curry Up Now, another Bay-area Indian concept, in May. Terms of the deal were not disclosed.

Reach Restaurant Group sold Mooyah Burgers, Fries & Shakes to a partnership led by Balmoral Funds LLC and Gala Capital Partners LLC in an April 2017 deal. The move means that the better burger chain will be primed for further growth, having entered several new states in 2016.

In May, The Chalak Mitra Group (parent to the Genghis Grill chain) announced the sale of three of its non-core brands: Elephant Bar Restaurant, Baker Bros. American Deli, and Ruby Tequila’s Mexican Kitchen. The 10-unit Elephant Bar was reportedly sold via stock purchase agreement to an affiliate of SBR LLC, a Connecticut investment company.

Star Buffet announced it had acquired The Rancher’s Grill steakhouse in Deming, New Mexico for an undisclosed amount in March, with the move expected to integrate the new restaurant into the company’s StarTexas Restaurants, Inc. subsidiary.

In July, PE firm Advent International announced its purchase of a majority stake in breakfast-and-lunch chain First Watch from Freeman Spogli & Co. In a statement released at the time, the firm’s managing director said the investment was an obvious one, as First Watch “is strongly aligned with trends toward healthier eating and better ingredients, and positioned to not only grow within existing markets but also to expand the unique concept to guests in new geographies.”

Roark Capital, parent to Carl’s Jr., Jimmy John’s, Arby’s and a slew of other restaurant chains, added the Jim ‘N Nick’s Bar-B-Q chain to its holdings in July. The price paid for a controlling interest in the 37-unit regional barbecue chain was not disclosed.

In July, six-unit Hawaiian chain Mo’Bettahs was acquired by Four Foods Group, parent to the Kneaders Bakery & Café chain, and a portfolio of brands including three units of R&R Barbecue, two locations of The Soda Shop, and 48 Little Caesars restaurants in Alabama and Louisiana.

After two potential buyers backed out of deals that would have seen them acquire the bankrupt Garden Fresh, the owner of Souplantaion and Sweet Tomatoes, Cerberus Capital Management swooped in. Terms of the January deal were not disclosed.

Tom + Chee, a Cincinnati-based grilled cheese restaurant chain, was acquired by Gold Star Chili, which bought the assets from its lender, and finalized the deal on September 20.

L Catterton, a consumer-focused private equity firm, announced in September that it had acquired Uncle Julio’s, a polished casual Mexican restaurant. Terms of the transaction were not disclosed.

Ruby Tuesday was sold for $2.40 a share, or $146 million, to a fund managed by private equity firm NRD Capital, the company announced in October. The deal includes the acquisition of all of the restaurant chain’s stock in cash.

Roark Capital made headlines in November when it announced a merger of Arby’s Restaurant Group and Buffalo Wild Wings. And the PE firm isn’t slowing down, with reports suggesting Roark is anxious to acquire other brands along the same lines of the chicken wing and sandwich chains, merging them all under one name — Inspiring Restaurant Brands — and eventually going public.

FAT (Fresh. Authentic. Tasty.) Brands Inc. (NASDAQ:FAT) announced in November that it had signed a definitive agreement to acquire Hurricane Grill & Wings for $12.5 million. The acquisition will be funded with cash on hand and third party financing, and was expected to close in 2017.

TPG Growth acquired a majority stake in Mendocino Farms, a California sandwich chain. The PE firm said it planned to use the acquisition to expand the concept outside the state.

One of the biggest restaurant M&A deals of 2017 was the announcement that Panera Bread was buying the Boston-based bakery-cafe chain Au Bon Pain for an undisclosed amount (announced in November). Panera was acquired earlier this year by the privately held investment firm JAB for $7.5 billion. The acquisition is part of Panera’s plan to expand its footprint beyond the traditional storefronts and into hospitals, universities, transportation centers, and urban locations.

TAZO — the tea company owned by Starbucks — would be acquired by Unilever. Under the asset purchase agreement, Unilever will acquire the TAZO® brand and all related intellectual property, signature recipes and inventory for US$384 million.

UK-based chain Yo! Sushi announced it would buy Canada’s Bento Sushi in a $78.2 million deal in November. The combined business will make the company one of the largest sushi companies outside of Japan.

Sodexo announced it had signed an agreement to acquire Centerplate, a food and beverage, merchandise and hospitality services provider at sports facilities, convention centers and entertainment facilities throughout the US, the UK, Canada and Spain. The deal was worth a reported $675 million and was expected to close by the end of 2017.

New York PE firm Beekman Investment Partners made a majority investment in breakfast concept Another Broken Egg in November. At the time of the announcement, the firm said it hoped to “build on the company’s legacy and accelerate growth.”

Brentwood Associates announced it had taken a significant stake in multi-concept company Upward Projects, which operates five brands (Windsor, Churn, Federal PIzza, Positano WineCafé and Joyride Taco House) and 12 restaurants in Arizona and Colorado. Terms of the deal were not disclosed, but the California PE firm already has a broad restaurant portfolio, with investments in Veggie Grill and Blaze Pizza, among others.

MTY Food Group Inc., owner of Kahala Brands, agreed to acquire the parent of The Counter and Built Custom Burgers brands, it announced in December. Terms of MTY’s planned acquisition of the California-based company were not disclosed.

Valor Equity Partners made a majority investment in Lettuce Entertain You Enterprises Inc.’s quick-service Wow Bao concept. The funding is expected to allow Wow Bao to open a delivery-only platform in Los Angeles and expand its brick and mortar presence.

In January, Palo Alto-based Symphony Technology Group announced it had acquired Fishbowl Inc., a customer engagement platform provider for the restaurant industry. Fishbowl helps restaurants optimize their marketing, strategy, and revenue management through advanced guest analytics software. Yelp acquired restaurant reservation app Nowait for $40 million in an all-cash deal in March. The deal worked to transition Nowait’s waitlist system and seating tool to Yelp, where it’s been integrated in the Yelp app and mobile food-ordering system, Yelp Eat24.

In August, Grubhub acquired Eat24 from Yelp for $287.5 million in cash. (Yelp paid less than half that price, $134 million in cash and stock, to acquire Eat24 in February 2015.) Yum China Holdings (the operator of KFC and Pizza Hut restaurant chains across the country) bought a controlling stake in Chinese food delivery service provider Daojia in May. No figures were released, though Reuters reported in November thatYum China was in talk to buy the company for roughly $200 million.

More companies have gone private than public in recent years, and the volume and value of M&A activity continues to rise.

When Ron Shaich announced his resignation as CEO of Panera Bread, he explained that he wanted to “really push this debate… about how short-termism has infused our capital markets.” The focus on short-term results, he went on, “stops innovation. It stops the very things that drive economic growth. And it makes us less competitive as an economy.” This is why Shaich took Panera private: so the company could focus on more complex, long-term strategies like digital integration that may reduce more immediate payouts but can significantly increase future returns.

Shaich’s harsh words for the industry have made the merger between Zoës Kitchen and Cava, financed by Shaich’s Act III, huge news. The two Mediterranean concepts have a combined footprint of almost 350 stores. Though Zoës has struggled with declining traffic, especially in regions where over-expansion resulted in self-cannibalization, Shaich’s involvement in this deal signals that the chain still has a lot of potential.

We’ve also seen this with Inspire Brands, another multi-concept portfolio under the Roark umbrella which acquired Dunkin’ Brands for $11.3 billion in 2020. It adds coffee (Dunkin’) and ice cream (Baskin Robbins) concepts to an empire that already includes Arby’s, Sonic, and Buffalo Wild Wings. The group has a proven track record for bringing back struggling concepts: since the Arby’s turnaround began in 2013, the roast beef restaurant chain has increased sales by 20%.

CEO Paul Brown focused on making the brand more appealing for young people: social media became less corporate, more emphasis was put on high-quality ingredients, and stores were remodeled (which also helped with efficiency). Like Shaich, Brown is focused on longer-term strategy, acquiring a multi-billion company every year and integrating them efficiently. The company is already the fourth-largest restaurant company in the world (and they only got started in 2017).

The volume and value of M&A activity continues to rise. With trillions sloshing around in the global private equity and alternative assets markets — and the rise of family offices with fortunes to invest — it is no surprise that the foodservice industry is a hot target.

What’s also shaping up though, is that investors, analysts, and innovators alike all share a sense of optimism and enthusiasm for the convergence of technological advancements, rapidly evolving consumer dining behaviors, massive stockpiles of corporate cash and investment capital, and the opportunity that spells for future of foodservice type investments.

The foodservice industry is being reshaped globally by delivery, self-ordering, alternative foodservice formats, tech-enabled turnarounds, and quickly changing dietary preferences. We’ve all read plenty about that. But, what not everyone is seeing yet is just how much more the performance of the industry, experience for the guest, and returns for investors can be as these trends accelerate and combine with other emerging ones to create super-trends.

Here, we take a look at some recent M&A activity to identify patterns and look broadly at the benefits and outcomes of companies accelerating growth through strategic acquisitions.

Restaurant mergers and acquisitions deals are gravitating more towards strategic buyers (rather than purely financial investors): the share of strategic deals increased 16% between 2004 and 2016. That suggests that a level of understanding (one supported by a specialist with knowledge of the external and internal factors affecting restaurants today and tomorrow) will be much-needed for deals in the future. We’ll likely see even more restaurant M&A deals in the future, thanks to more funding flowing into the space.

More investment is being placed into high-growth concepts — those in categories like snacking and coffee, rather than in slumping segments like casual dining. Outdated concepts in saturated sectors will struggle to find buyers, while on-trend concepts will likely prove to be the most worthy investments.

Restaurants with no physical locations have been cropping up around the country, largely in response to the success of delivery platforms like UberEATS and GrubHub. For restaurant concepts, the move is a win-win. A recent report by Fast Company found that many fast-casual restaurants dedicate 75% of their stores to seating, while some 90% of their customers take their meals to-go. A “ghost” storefront — in which customers can order their meals to have it delivered, but never actually go in the restaurant — certainly solves that problem. It also remedies high rent costs, as delivery-only units don’t necessarily have to be located in busy, walkable (i.e. high rent) locations.

While other sectors have historically seen significant increases in productivity, improvements in the foodservice industry have been minimal over the last 30 years. The Second Industrial Revolution benefited the industry (overall) with improvements in agricultural production. The Third Industrial Revolution, where consumer and electronics products led growth, had a very slight impact on foodservice, with the adoption of the point of sale system — most of which are really a glorified cash register.

But the sector is now in a prime position to make modernization efforts with the impacts of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and — in doing so — is becoming a more attractive target for investment.

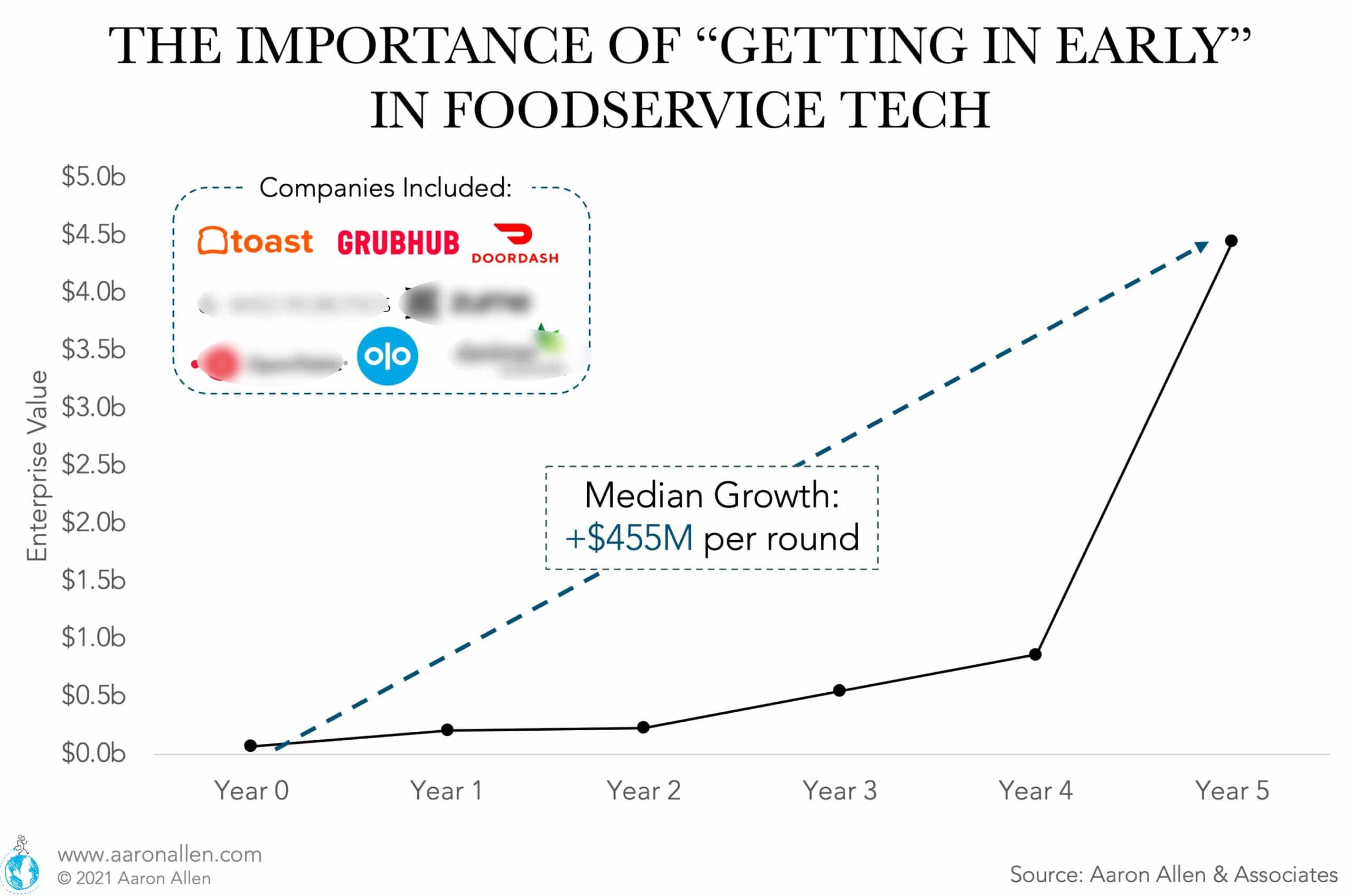

In our view, we’re still living in the bronze age of foodservice tech, where most of the category’s success stories are largely-delivery focused (including DoorDash, GrubHub, and Olo). However, as operators begin to rethink their operating models for a post-pandemic world and may be more open to new technology solutions, there are several reasons to be bullish about the future of foodservice tech investing:

We took a small sample of foodservice tech companies (including categories like delivery, POS, robotics, SaaS, and more) and calculated that on average, enterprise value grows $455 million per funding round (from Seed Round and Series A onwards). Investors getting in early can see huge valuation growth.

Jollibee, for instance, finalized its acquisition of Denver-based Smashburger in 2018. The company initially tried to expand to other markets and they met unforeseen challenges and struggled because customers outside of the Philippines were unfamiliar with the brand. But Jollibee does know QSR operations well, so they looked for an opportunity in the U.S. with a large enough footprint to gain scale.

Larger foodservice groups have been using cross-border transactions to grow for a while now. Growth in the U.S. for large established companies is at a point of saturation — any new units for one brand are coming at the expense of someone else. So inorganic growth and foreign expansion are the greatest opportunities.

We anticipate more foreign buyers coming to the U.S., and U.S.-based investors making further investments globally. This strategy is a way to gain immediate access to a footprint, infrastructure, talent and human resources, and a regionalized know-how.

Here are some key phrases used in the mergers and acquisitions world:

There are a lot of moving pieces and parts when it comes to making a successful restaurant acquisition. And the companies that are most successful in their efforts are those that hire talented and experienced advisors, versus doing everything in-house.

There’s a need for legal, financial, technological, and operations expertise. And while many restaurant companies have much of this in-house — or even may have gained the talent and IP in these areas through the acquisition process — it’s often overly taxing and a burden to the system when going through an acquisition on top of building out and making more efficient the existing operations.

Whether taking some chips off the table by divesting a few units, bringing on a partner, or even a full sale of the business, expert advisors can help find the right investor, guide and accelerate the investment process and give a second opinion on what’s a fair valuation.

Seeking out new opportunities can be greatly benefitted with a partner to help lighten the load — particularly when that partner has specialized expertise across functional areas critical to the M&A landscape.

There’s plenty of capital to put behind foodservice companies, but what not everyone is seeing yet is just how much more the performance of the industry, experience for the guest, and returns for investors are shifting between segments, categories, cuisines, geographies, and formats. Some that are not even on the radar right now (or that have a strong base to pivot in the right direction) will jump to very large valuations in the next few years.

Those leveraging the best insights, expertise, and representation to build a modernized and globally oriented F&B investment thesis are set to lead (and even create) foodservice segments and categories.

We help middle-market foodservice companies and investors as both buy- and sell-side M&A advisors. Our clients include restaurant chains, foodservice technology providers, and alternative foodservice formats. We also specialize in multinational, multi-brand portfolios, and cross-border transactions.

Our restaurant and foodservice industry M&A advisory services include:

Going beyond the three financial statement models to identify and unlock trapped potential and value-accretive opportunities by building a perspective from the most granular-level data to the big picture of a global marketplace, we apply a data-driven, analytical process combined with deep and specialized foodservice industry experience and expertise.

We are focused exclusively on the global foodservice and hospitality industry. You can think of us as a research company, think tank, innovation lab, management consultancy, or strategy firm. Our clients count on us to deliver on our promises of meaningful value, actionable insights, and tangible results.

Founded and led by third-generation restaurateur, Aaron Allen, our team is comprised of experts with backgrounds in operations, marketing, finance, and business functions essential in a multi-unit operating environment.

We bring practical, relevant experience ranging from the dish room to the boardroom and apply a holistic, integrated approach to strategic issues related to growth and expansion, performance optimization, and enterprise value enhancement.

Working primarily with multi-brand, multinational organizations, our firm has helped clients on 6 continents, in 100 countries, collectively posting more than $300b in revenue, across 2,000+ engagements.

We help executive teams bridge the gap between what’s happening inside and outside the business so they can find, size, and seize the greatest opportunities for their organizations.