We’ve gone on record about digital delivery’s disruptive and ultimately transformative effect on the restaurant industry: as online food delivery and mobile ordering apps reshape consumer expectations for speed and convenience, operators have to keep pace with these demands or watch their sales drop.

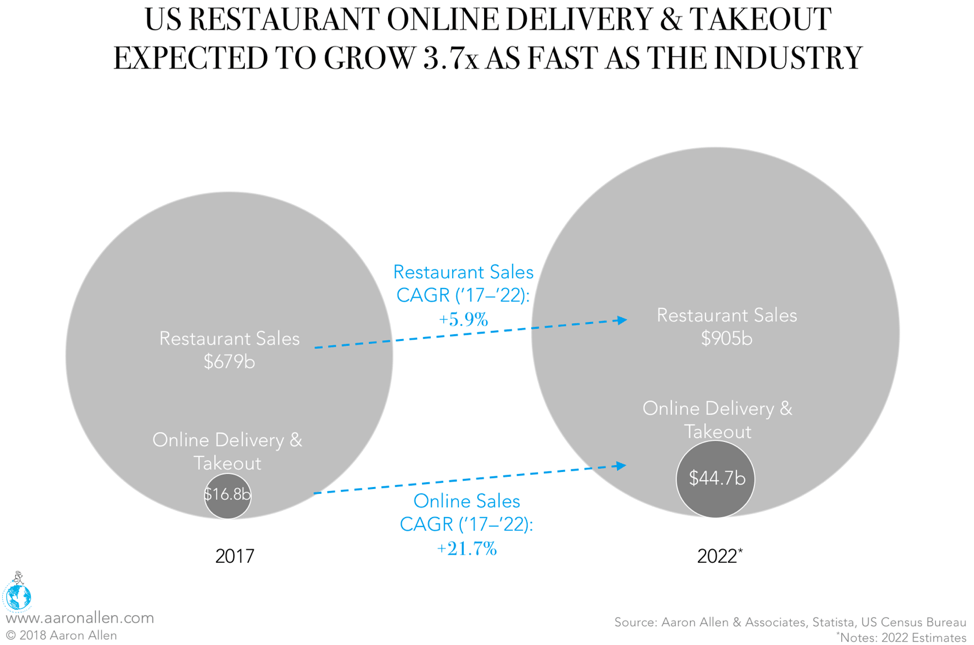

Our projections show that this market will continue to grow, at a pace almost four times as fast as the foodservice industry itself. While restaurant sales are expected to grow at a 5.9% CAGR over the next five years, delivery and takeout will grow at a 21.7% CAGR. Online orders’ share of restaurant sales will likely double over this time period, from 2.5% in 2017 to 4.9% in 2022.

Globally, consumers are spending an average $247.10 on four of the largest delivery companies. The average transaction runs between $16.00 for German company Delivery Hero and $31.20 for Grubhub, which operates in the US and UK.

If you’ve been following our newsletter, then you know we’ve been digging deep into the companies that are driving these changes. What we’ve discovered shows not only that investments in digital delivery are growing at an incredible rate, but also that this still-new segment is showing remarkable returns on those investments.

This has created an incredibly competitive environment as service providers carve up the market in hopes of claiming particular segments and geographies for themselves. Meanwhile, a flurry of mergers and acquisitions are leading to greater consolidation.

In December 2016, Just Eat bought Delivery Hero’s UK operation, called hungryhouse, as well as Canada’s SkipTheDishes, and just last month, China’s massive Alibaba scooped up Ele.me in hopes of cornering food delivery market in that country. It’s been reported that DoorDash and Postmates are discussing a merger in hopes of surviving the combined onslaught of Grubhub, Uber Eats, and Amazon, which, with its purchase of Whole Foods, is gaining traction in the grocery-delivery market. This land grab is likely to continue until each segment and market has its own leading provider. What will set the winners of this battle apart will not only be consumer-facing service but also how well they serve the restaurants that form the basis of their business. While these organizations started as tech companies, they need to start thinking like foodservice operators.

Grubhub: Incredible Growth, Strong Fundamentals

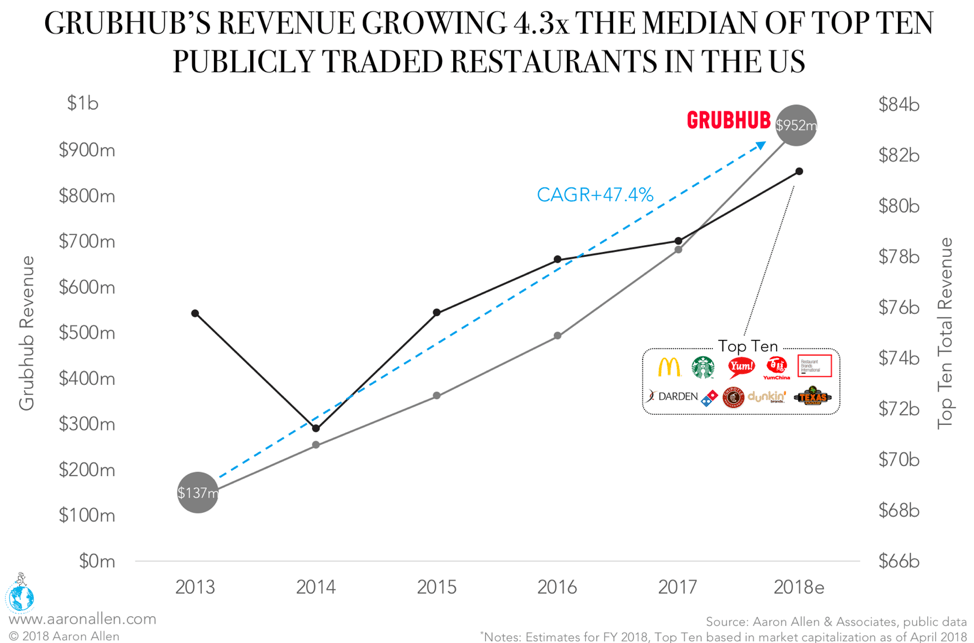

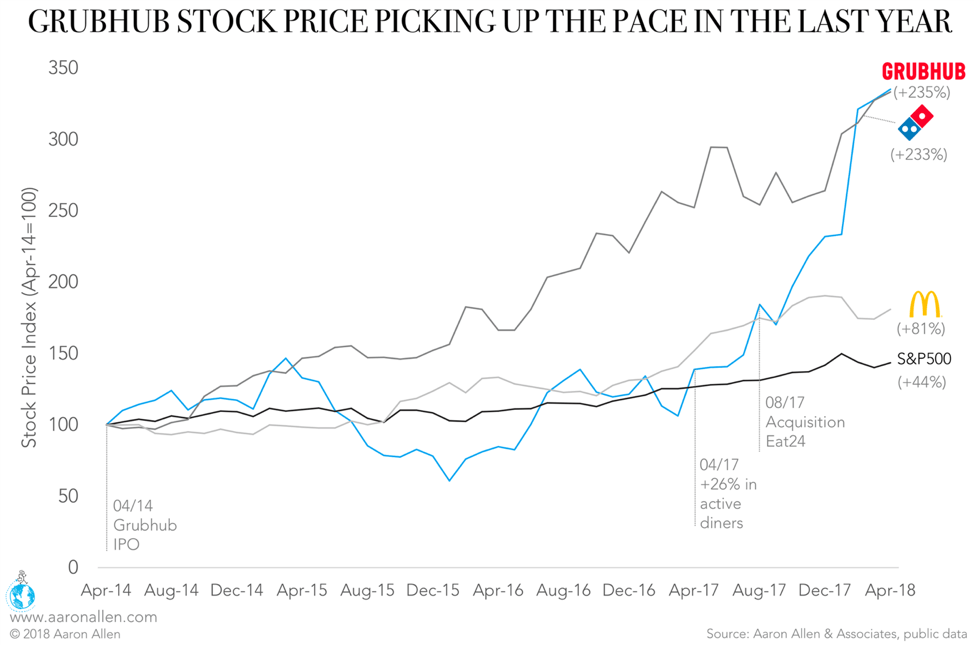

In the US, Grubhub has had much higher — and more sustained — revenue growth than the top ten publicly traded restaurants. These chains, which include McDonald’s, Starbucks, and Chipotle, have seen their revenue grow at a median 11.1% CAGR since 2013, but Grubhub has outpaced them by 3.3x, with a 47.4% CAGR.

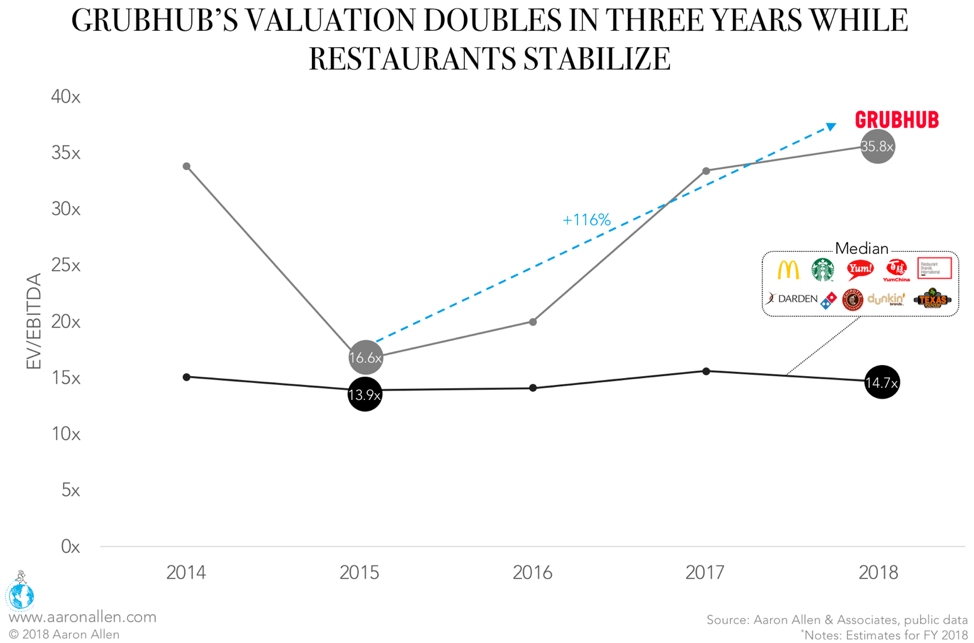

Not only that, but Grubhub’s trajectory has been much steadier, growing from $137m in 2013 to a projected $952m in 2018. In contrast, chains had a lot of ground to make up after a massive drop in revenue in 2014. When it comes to valuation, the top ten chains have been posting respectable EV/EBITDA ratios for the past five years. (They average 14.7x; the S&P average for 2017 was 12.8x.) Grubhub’s, however, is growing by leaps and bounds to 35.8x (+116% since 2015).

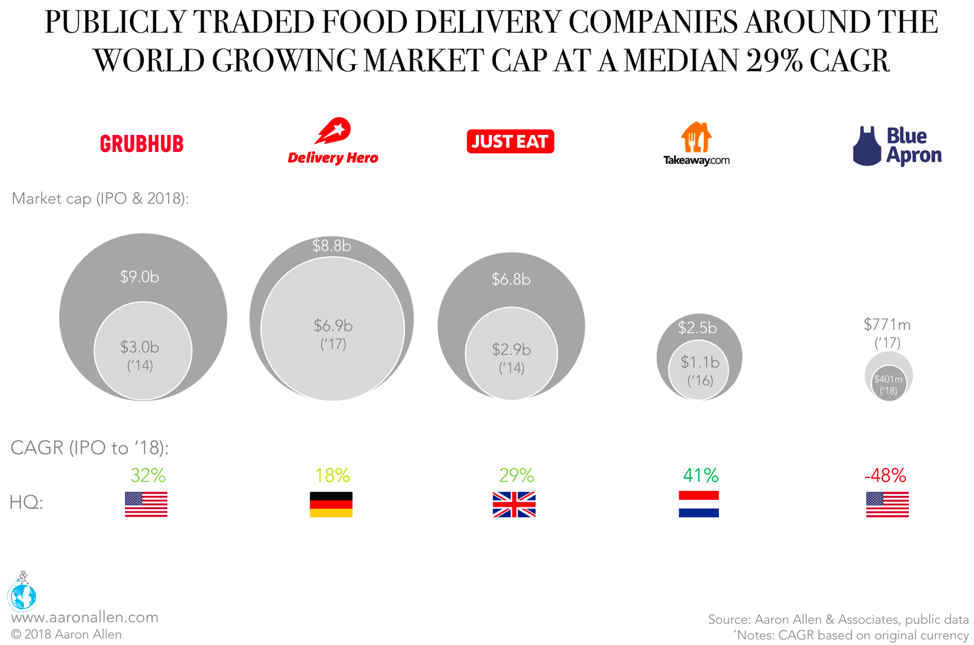

Of course, not all delivery companies are created equal. While services that provide meals to people’s homes are seeing their market caps grow at a median 29% CAGR, the American meal-kit delivery company Blue Apron has lost almost half (-48%) of its capitalization since its IPO last year.

Blue Apron’s problems appear throughout its financials. Its EV is just 0.33x its sales, a number that seems to point to undervaluation until we look at its EBITDA margin (-9%), which reveals serious underlying problems.

This data suggests a number of possible interpretations. Blue Apron is working in an incredibly competitive sector, as other tech companies, like Instacart and Amazon, have started offering grocery deliveries. Even Target has started offering curbside delivery. At the same time, Blue Apron has been dogged by labor safety violations that have produced investor lawsuits and hurt every single aspect of the company’s operation.

In a recent newsletter, we proposed an alternative suggestion: convenience-seeking diners aren’t looking for food delivered to their doors; they want meals delivered to their doors. The data might also indicate that people aren’t interested in subscriptions, preferring instead to make their dinner decisions at the last minute, based on how much time they have and what they’re craving.

More research into consumer preferences is necessary before we know exactly why Blue Apron is performing so poorly, but it’s clear that Grubhub is winning the battle. Compared to the meal-kit provider’s 0.33x valuation and -9% EBITDA margin, the delivery aggregator had a 9.43x valuation and 26% EBITDA.

Become Indispensable

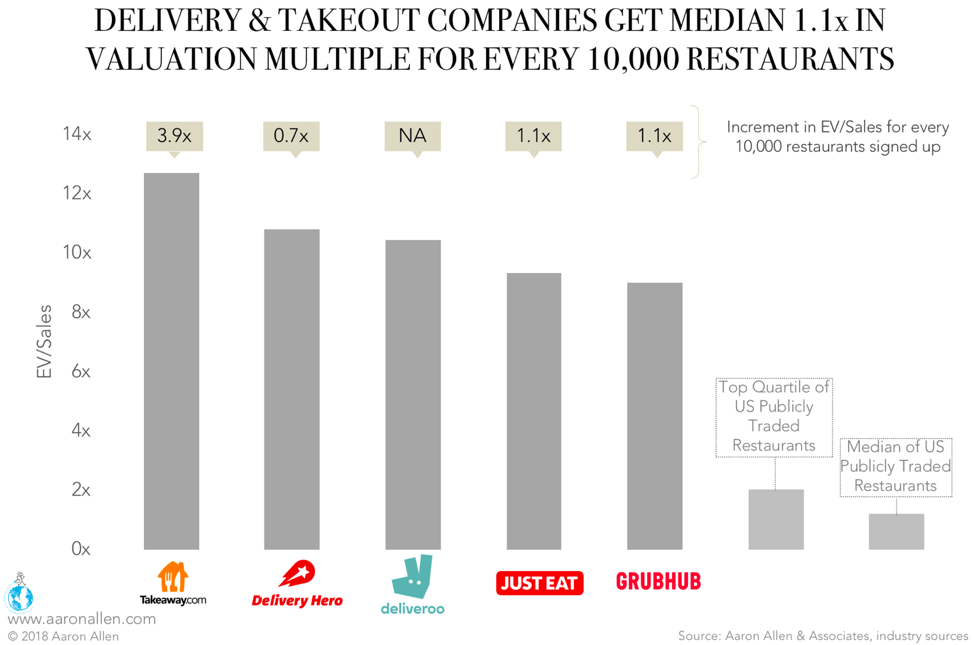

These delivery companies’ success is built on their restaurant partners. Our data shows that delivery and takeout companies’ valuations equal a median 1.1x sales for every 10,000 restaurants they work with.

This is fairly simple math, but, when compared to even the highest-performing publicly traded restaurants, we find an incredible gap. The top quartile of public foodservice companies has a 2.02x EV-to-sales ratio; Grubhub, which works with some 80,000 restaurants, has more than four times, with a 9.00x valuation multiple.

Even more stunning is the Dutch company Takeaway.com. With just 33,000 restaurant partners, it’s posting a 12.7x valuation multiple.

Thanks to the immense value at stake, providers are battling to sign partnerships from the most sought-after restaurants, and we can expect the pace of mergers and acquisitions in this segment to continue to accelerate.

Of course, restaurants are getting something out of the deal as well. They’re are earning between $31,000 (for German Delivery Hero) to $55,000 (for British Just Eat) in revenue through these services. More research is needed to determine how much of this revenue is incremental and how much represents a cannibalization of existing orders.

Most delivery service providers have focused on winning over consumers by offering discounts and coupons, multiple ways to access the service (via desktop, mobile, Smart TV, and so on), and, of course, the most popular restaurants. This makes sense, considering how sticky these apps are for customers: some studies indicate that about three-quarters of consumers stick with the very first provider they try. (Anecdotally, one member of our staff downloaded the Grubhub app when it first came out and has never tried another service; everyone else is much more adventurous.)

Now, the smartest and most agile of these companies will shift their attention to restaurants, offering services specifically designed to help operators increase sales and revenue.

This requires a radical re-understanding of their core business. After all, Grubhub, Uber Eats, and DoorDash are technology companies first: they created a platform that connects restaurants to hungry consumers and, in some cases, a fleet of delivery staff. Domino’s CEO Patrick Doyle has described his operation as a tech company that sells pizzas — a pivot that, as we’ll see in a moment, is paying off handsomely. But now, delivery companies need to develop a deep understanding of the needs and concerns of restaurant operators or risk losing them to competitors or in-house apps.

As we saw above, restaurants of all sizes and from all segments get clear benefits by signing with delivery services — not only does it grow revenue, but it builds new customer bases, increases order size and frequency, and provides the restaurant with mobile ordering capabilities and, in some cases, dedicated delivery staff.

At the same time, delivery charges take away between 13% and 18% (on average) of this new revenue. Further, savvy restaurant operators might take a look at this data — the incredible valuations, the strong EV/Sales ratios, and the booming stock prices — and decide they shouldn’t hand all this over to a third party.

For example, of publicly traded restaurant companies, only Domino’s Pizza comes close to matching Grubhub’s impressive stock-price rise, which we see skyrocketed with its acquisition of competitor Eat24 in August 2017. What sets Domino’s apart from McDonald’s is that the pizza chain has innovated on its own to offer its consumers a variety of different ways to make and receive orders. The delivery providers that can give these restaurants something they can’t develop on their own — becoming indispensable to sales and operations — are the ones that will survive.

A lot of uncertainty remains as delivery providers further carve up the foodservice market then merge with and/or acquire competitors to increase market share. What remains clear is that there is a lot of revenue and value up for grabs here, and those who innovate first will have higher chances of claiming it.