Aaron Allen » Insights » Casual Dining Restaurant Chains Entering Dangerous Waters

Aaron Allen » Insights » Casual Dining Restaurant Chains Entering Dangerous Waters

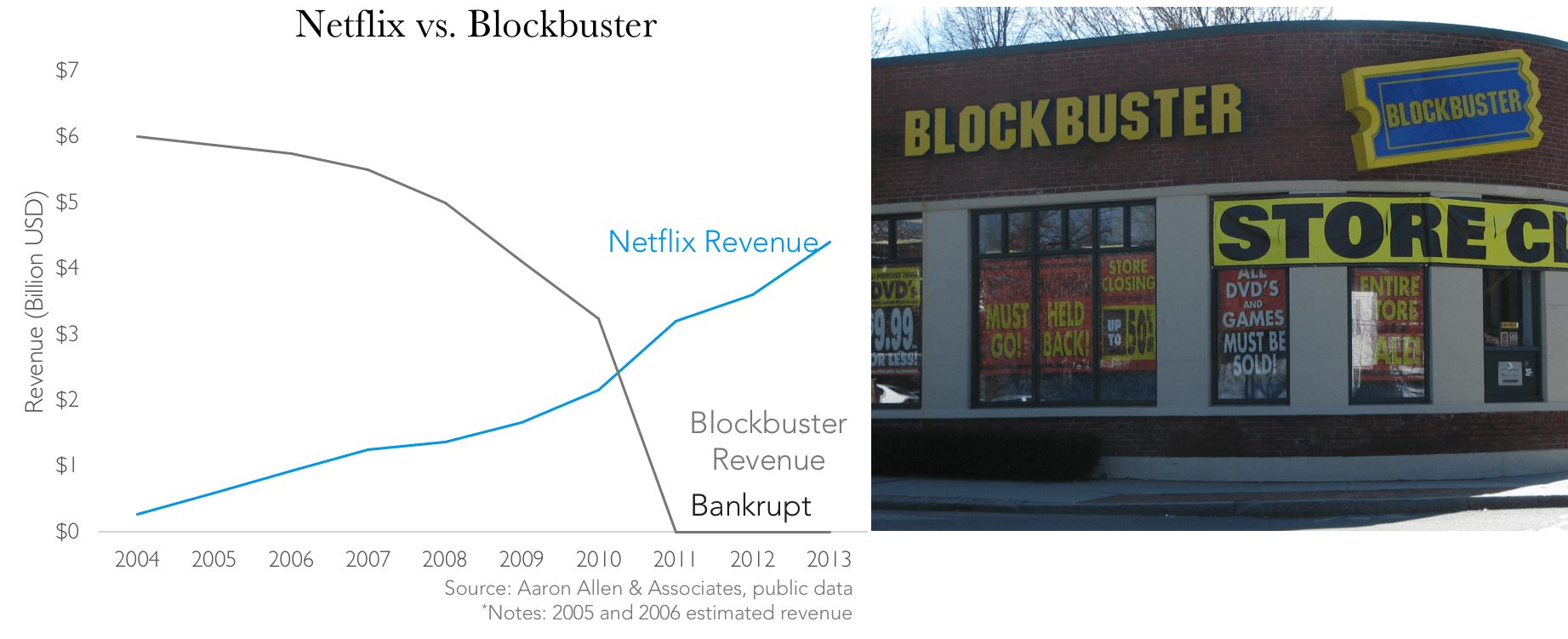

Imagine what sighs, dismissiveness, and down-right animosity Blockbuster’s internal and external advisors must have been met with in 2007 (or earlier) when they warned of the potential threat posed by Netflix. That 2016 was the worst year for casual dining since the recession isn’t too surprising to those of us who study the industry — or those within Casual Dining Restaurants (CDRs) tasked with explaining their poor performance to the public. So far, CDRs haven’t fared much better in 2017. The first few days of May brought news that the owner of Joe’s Crab Shack and Brick House Tavern was said to be preparing a bankruptcy filing. The fact is, we didn’t arrive here overnight, but because of rapid changes over the past several years — changes that many chains were too slow to adapt to. In a sense, some casual dining chains have become the Blockbuster of the restaurant world, failing to forecast where the industry will likely go, and looking only to their historic competitors; lacking the more precise instruments of measurement and new voices and languages they need to navigate unfamiliar waters critical to finding a profitable new way forward. Many CDR chains are sadly adrift in the sea of same; their captains and crew made anxious by the rough waters rolling their ships, and tightly clinched anticipating the hairpin turns required to sail clear of the jetties that wait ahead. We’ll explore the causes (and solutions) for the sinking ship that is the casual dining industry below.

Imagine what sighs, dismissiveness, and down-right animosity Blockbuster’s internal and external advisors must have been met with in 2007 (or earlier) when they warned of the potential threat posed by Netflix. That 2016 was the worst year for casual dining since the recession isn’t too surprising to those of us who study the industry — or those within Casual Dining Restaurants (CDRs) tasked with explaining their poor performance to the public. So far, CDRs haven’t fared much better in 2017. The first few days of May brought news that the owner of Joe’s Crab Shack and Brick House Tavern was said to be preparing a bankruptcy filing. The fact is, we didn’t arrive here overnight, but because of rapid changes over the past several years — changes that many chains were too slow to adapt to. In a sense, some casual dining chains have become the Blockbuster of the restaurant world, failing to forecast where the industry will likely go, and looking only to their historic competitors; lacking the more precise instruments of measurement and new voices and languages they need to navigate unfamiliar waters critical to finding a profitable new way forward. Many CDR chains are sadly adrift in the sea of same; their captains and crew made anxious by the rough waters rolling their ships, and tightly clinched anticipating the hairpin turns required to sail clear of the jetties that wait ahead. We’ll explore the causes (and solutions) for the sinking ship that is the casual dining industry below.The numbers speak for themselves: over the last decade, the casual-dining segment experienced no growth whatsoever.

The corporate culture so woven into the CDR segment stifles creativity, and conformity often wins out over ingenuity in a mature brand. There’s no question that retail will change significantly over the next five to 10 years. Foodservice chains, too, will be forced to adjust to keep up with ever-evolving restaurant trends. The chains that will fare the best in the months and years ahead are those that take note of what’s coming, opting to be proactive, rather than reacting to social shifts years too late.

A cursory glance at the menus of the leading CDRs reveals a sea of the same — similar colors, fonts, and even menu items.

Even the exteriors of CDR chains are starting to resemble one another — from the red awnings to the architecture of the buildings:

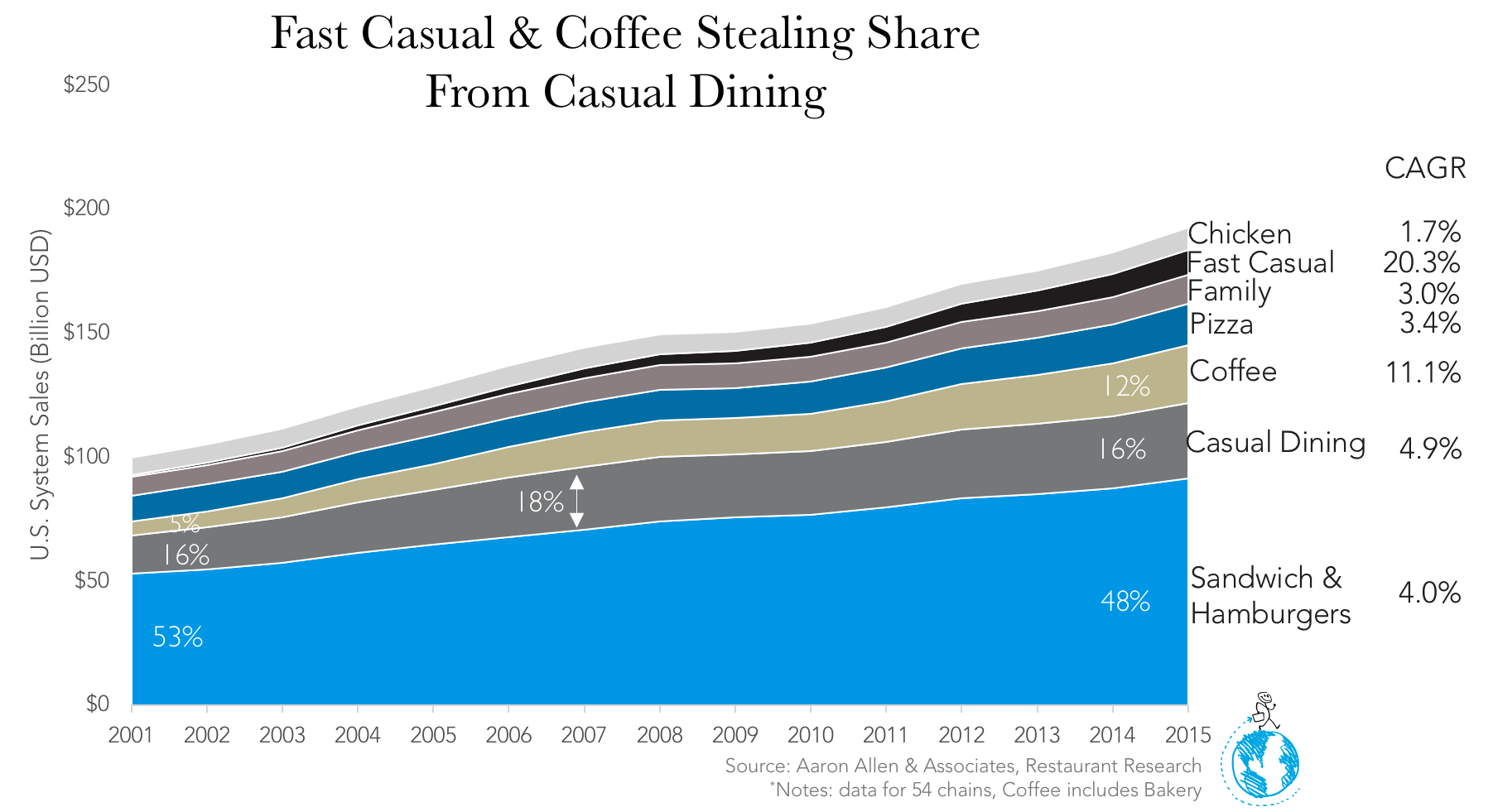

In 2002, sales at CDRs were growing at a successful rate, outpacing sales at quick-service and pizza chains. By 2015, though, the tables had turned, with CDRs registering the weakest growth of all the restaurant categories. The fast-casual segment alone was now eclipsing CDRs by 68%.

While CDRs are trying to hedge against fast-casual chains by lowering prices, QSR brands also started improving quality while still retaining their affordable prices. Arby’s, for instance (one of the best brand turnarounds seen in years), has upped its quality, while still maintaining a QSR price point and offering strikingly similar sandwiches as some casual chains, albeit at lower prices.

And as enticing as they may be, short-term, tactical promotions often erode long-term value. Still, many full-service chains have resorted to low-priced offers, in an attempt to mimic the price point of fast casual, or the 2-for-whatever style value offers of the casual dining industry (2 for $2 or 2 for $20 still conjure a familiar association for the consumer; now likening QSR’s and CDR’s in the mind of the consumer). Profitable, loyal consumers don’t want “cheap.” They want value and convenience. Casual dining chains cannot be as fast, as convenient, or as low-priced as QSR or fast casual chains and succeed in the long-term.

When comparing 2001 to 2015, it appears that CDRs retained their share in sales. However, after reaching a peak in 2007, at 18% of the market, CDRs have decreased in market share (down to 16%). The reason? Different, more convenient, ways of eating (fast-casual, pizza 2.0, better tech-enabled delivery, home meal replacement, meal kits, food trucks, snacking, etc.) have been stealing share like unapologetic, gun-slinging bandits raiding rail-drawn bank deposits.

Starbucks alone has dramatically altered the landscape (and in a gracious, charismatic, kind, and gentlemanly fashion that sets the stage for a new king of foodservice to be crowned soon). The chain’s share in the coffee segment was 40% in 2001 and increased to 62% by 2015. Over this period, Starbucks grew almost twice as fast as its competitors in the same segment (Starbucks’ CAGR was 14.5% while the Coffee segment without Starbucks grew at a CAGR of 7.6%).

Chipotle’s share in the fast-casual segment more than doubled in fifteen years: the company had a 20% share of the segment in 2001, which was up to 43% by 2015. The burrito giant grew leaps ahead of the competition with a CAGR of 27.3%. The CAGR of the fast-casual segment without Chipotle would have been 17.4% (instead of 20.3%), almost ten percentage points below Chipotle’s growth. Of course, the chain has gone off message in the years since, but the company still deserves praise for the growth that came thanks to its initial messaging and innovation.

Agricultural commodity prices – and, as a result, grocery prices – have fallen, but that’s not the only reason people are straying from their neighborhood grille. Meal kits, a $1.5 billion-and-growing industry, have taken share from restaurants. So has delivery, which is estimated to be worth some $210 billion.

Each of these options offer convenience, and merge seamlessly with technology. CDRs are woefully behind in terms of tech – with many of them not offering delivery, self-ordering, or online ordering at all, alongside antiquated and “me-too” marketing.

And there’s urbanization. While casual chains are designed to thrive in suburban areas (due to their larger footprint), consumers are increasingly moving into cities. According to the United Nations, projections show this migration – combined with the overall growth of the world’s population – could add another 2.5 billion people to urban areas by 2050. Why make the trek to the suburbs, just to dine solo in large dining room, when you could have food at the touch of a button via a Domino’s delivery bot, Panera grab-and-go, order Taco Bell via #slack, or simply tell Alexa what you want? It’s either that, or head out for an “experience” (woefully lacking at many tired CDR chains).

The year 2016 saw several headlines about the casual dining industry – and few of them were positive. From Ruby Tuesday to TGI Fridays, it seems even many of the most notable players in the segment weren’t immune from unit closings brought on by poor sales and traffic. The news continued into 2017. In May, Applebee’s announced that domestic same-store sales were down nearly 8% in the first quarter, news that came on the heels of a 7.2% decline during the previous quarter. The company, which has already shuttered 18 stores in 2017, could close some 3% of all stores by the time the year is over.

The numbers are, of course, startling. The value of more than half of the leading CDR chains has decreased in recent years. Meanwhile, companies that might not have historically been in direct competition (ahem, Domino’s) continued to grow.

In a last-ditch effort, some chains are resorting to re-franchising or franchising internationally — the result of which is that America seems to be exporting its half-eaten leftovers. Ruby Tuesday, for instance, just signed a development agreement to expand its presence in Qatar, while Bloomin’ Brands just sold 45 company-owned Outback Steakhouses to franchisees.

The casual dining problem isn’t relegated to the U.S. Iconic British roadside chain Little Chef raised fears that its locations could be wiped out entirely when it announced it would close 67 stores due to poor performance. Analysts have warned that the UK restaurant business is in dire straits, with some 5,570 restaurants in danger of insolvency due to inflation, stagnant disposable incomes, and — of course — many of the same issues illustrated here.

Still, the news isn’t all bad. Unfortunately, a lot of players in the category have been too slow in adjusting to evolving consumer habits, and wary of the risks that come with innovation. This is, however, a compelling proof point that casual dining is ripe for M&A and consolidation. While every other foodservice category has a clear market share leader, casual dining remains the exception. Many of the brands listed above aren’t necessarily new in the U.S., but they still have potential in other markets.

It’s a fact of life and one of business: Companies are born, they grow up, mature, decline, they die, and are eventually reabsorbed into the earth, to be reincarnated in some new form or fashion. The CDR category has become oversaturated — only the strongest and most adaptable will survive. As for the others, well, some will go away and others might be reincarnated anew. Restaurant brands must be refreshed every few years, before it’s too late.

Though we’ve said before that casual dining is dying, full-service restaurants will never disappear fully. But that sentiment offers little solace to the ghosts of brands bankrupted by drifting with the winds and currents instead of harnessing them, the wreckage gurgling between the jagged rocks and jetties, as if there to remind other captains and sailors of the risks of lackadaisical navigation and stewardship. It’s not just those aboard the vessel that pay the cost — investors, employees and their families, creditors, vendors, nearby retailers, all suffer from these avoidable losses.

So, how can CDRs work to stay afloat?

The CDR move toward discounting runs counterintuitive to what those brands have been built on: a full-service experience. Fast casual chains are, by design, generally fast and inexpensive — but inherent to their business model is less service and fewer employees. Sit-down (full-service) chains should offer a level of service and guest experience fast casual chains can’t. Considering that studies show customer complaints regarding service are up some 47% in two years, casual dining chains should leverage the service that sets them apart.

The challenges (and state) of the CDR segment are understandable. Even some of the best and most successful in our industry have suffered, which just speaks to how fast the pace of change has swallowed up yesterday’s best practices and approaches. We’ve long advocated that “fresh” is the most bankable word in foodservice, and the argument could certainly be built that “fresh” thinking and new approaches are sorely needed in CDR headquarters, as well.

In the modern world, innovation should be a mantra, not a meaningless buzzword. The fast-casual world has certainly caught on. At Panera, tech fueled sales and foot traffic and had a tremendous impact on the guest experience, shaving literally lifetimes off customer wait times.

Rather than play “follow the leader” with regard to tech trends and innovation, put efforts into finding (and developing) the required technology to be truly innovative. The pace of change will further widen the gap between industry leaders and those who still haven’t left the starting line (and those taking a “wait and see” approach will be writing their final chapters, whether it be 7, 11, or 13.)

One recent survey found that nearly 50% of companies believe analytics to be a key factor in decision-making, and two-thirds feel it helps drive business strategy. While it seems like businesses everywhere are using the term “analytics” these days, few are fully utilizing the power of big data, but are actually still swapping Excel spreadsheets by email.

The importance of applying analytics to a business increases every day. More data is produced every 48 hours than the first 5,000 of human civilization. It’s staggering, really, and many businesses aren’t able to keep up.

The most successful restaurant brands have something inherent in their DNA — something that sets them apart and draws guests in. Yet, over the years, many CDRs have neglected their unique differentiators and, as a result, they’ve lost touch with their history.

One prominent example is Applebee’s, the “neighborhood grill & bar” that made a $75 million bet that wood-fired grills would revitalize its brand. Not exactly the boldest move for a chain that’s very foundation was built on the word “grill.”

A unique culinary point-of-view and signature items seem like no-brainers for restaurants. While this might have been lost in trying to keep up with the competition, being the only who does what you do is a far more favorable marketing position than competing to be the “best of the best” (betterness is subjective, differentiation is objective).

Nearly every successful restaurant turnaround had a new menu strategy as the cornerstone of its brand renaissance. In late 2016, BJ’s Restaurants delivered a solid performance — and saw its shares climb — after expanding its most popular menu items, albeit at more compelling price points.

In many cases, signature items (or signature menu strategies) are what created category leaders (think PF Chang’s Lettuce Wraps or Chipotle’s “Food with Integrity” company POV). Of course, for an item or culinary strategy to be “signature” requires that it be unique and deliver on all-important metrics: customer satisfaction, profit maximization, revenue growth, etc. The most popular signature items are those reflecting a restaurant’s own distinct brand positioning, personality, promise and story.

People buy brands that reflect how they see themselves. Understanding this simple truth is key to unlocking that brand’s competitive differentiation and unique appeal. Every restaurant can compete in terms of price, and every restaurant promises good food and quality service. But to really grasp a brand’s full potential, chains must dig deeper.

All elements of a brand should be built on top of purpose (beyond profits). After defining this purpose, brands can articulate a sort of “constitution” which serves as a guiding document to help shape all future brand developments. Before investing in new advertising campaigns, revamping exteriors, or discussing pricing strategy, focusing on purpose is key to ensure all other decisions make sense within the bigger picture. Only six percent of consumers believe that the sole purpose of a business is to make a profit and companies with purpose see customers who are 93% more loyal to the brand.

You can never make it too easy to buy from you — a lesson that Outback helped teach others in the CDR space when it rolled out its curbside program. The success of that program not only changed the life of its inventor (ultimately catapulting a General Manager into the position of company President), but eventually contributed 19% of total unit-level sales. In fact, the convenience of curbside service helped bolster the chain’s takeout sales from $104 million in 2000 to $274 million in just five years.

Still, in the years since, many CDRs have fallen behind, now rapidly trying to play catch-up with self-ordering tablets and order-ahead capabilities. Innovative experience engineering goes beyond that, though — not thinking about how to piggy-back on a trend but how to create one.

Boardrooms and C-suites — in any company — become a vacuum over time. And to gain a more complete perspective requires a diversity of ideas (which study after study reveals is most successful when driven by a commitment from company leaders). Any meaningful commitment to change will require a change within the company itself — a change in thought, and a resolve to try something new.

Corporate culture can become the worst enemy to remaining relevant. Executives walk in to the same culture day after day, evaluating and evangelizing the brand without fault or critical eye. Not only do those thoughts take a toll professionally, but they cause leadership — and, in effect, chains and crews — to lose touch with the realities of an evolving industry.

Not only is there still hope, but there’s much opportunity in the realm of casual dining. Great service – when your server doesn’t just take your order, but truly anticipates your needs – is a lesson lost in some rungs of leadership. It’s not enough to just keep up and simply meet deliberately expressed orders from their guests. Instead, chains should be anticipating where (and how quickly) consumers are migrating. In the choppy waters of an ever-competitive industry, those who don’t forge ahead risk being forced in a new direction by the wakes of their competitors.

* * *

Aaron Allen & Associates is a global restaurant industry consultancy specializing in brand strategy, turnarounds, and value enhancement for leading hospitality companies and prestigious private equity firms. Aaron, a third-generation restaurateur, has personally led more than 2,000 senior-level strategy engagements across 70 countries and 6 continents. Collectively, our clients around the globe generate over $200 billion annually and span more than 100 countries.

We are focused exclusively on the global foodservice and hospitality industry. You can think of us as a research company, think tank, innovation lab, management consultancy, or strategy firm. Our clients count on us to deliver on our promises of meaningful value, actionable insights, and tangible results.

Founded and led by third-generation restaurateur, Aaron Allen, our team is comprised of experts with backgrounds in operations, marketing, finance, and business functions essential in a multi-unit operating environment.

We bring practical, relevant experience ranging from the dish room to the boardroom and apply a holistic, integrated approach to strategic issues related to growth and expansion, performance optimization, and enterprise value enhancement.

Working primarily with multi-brand, multinational organizations, our firm has helped clients on 6 continents, in 100 countries, collectively posting more than $300b in revenue, across 2,000+ engagements.

We help executive teams bridge the gap between what’s happening inside and outside the business so they can find, size, and seize the greatest opportunities for their organizations.