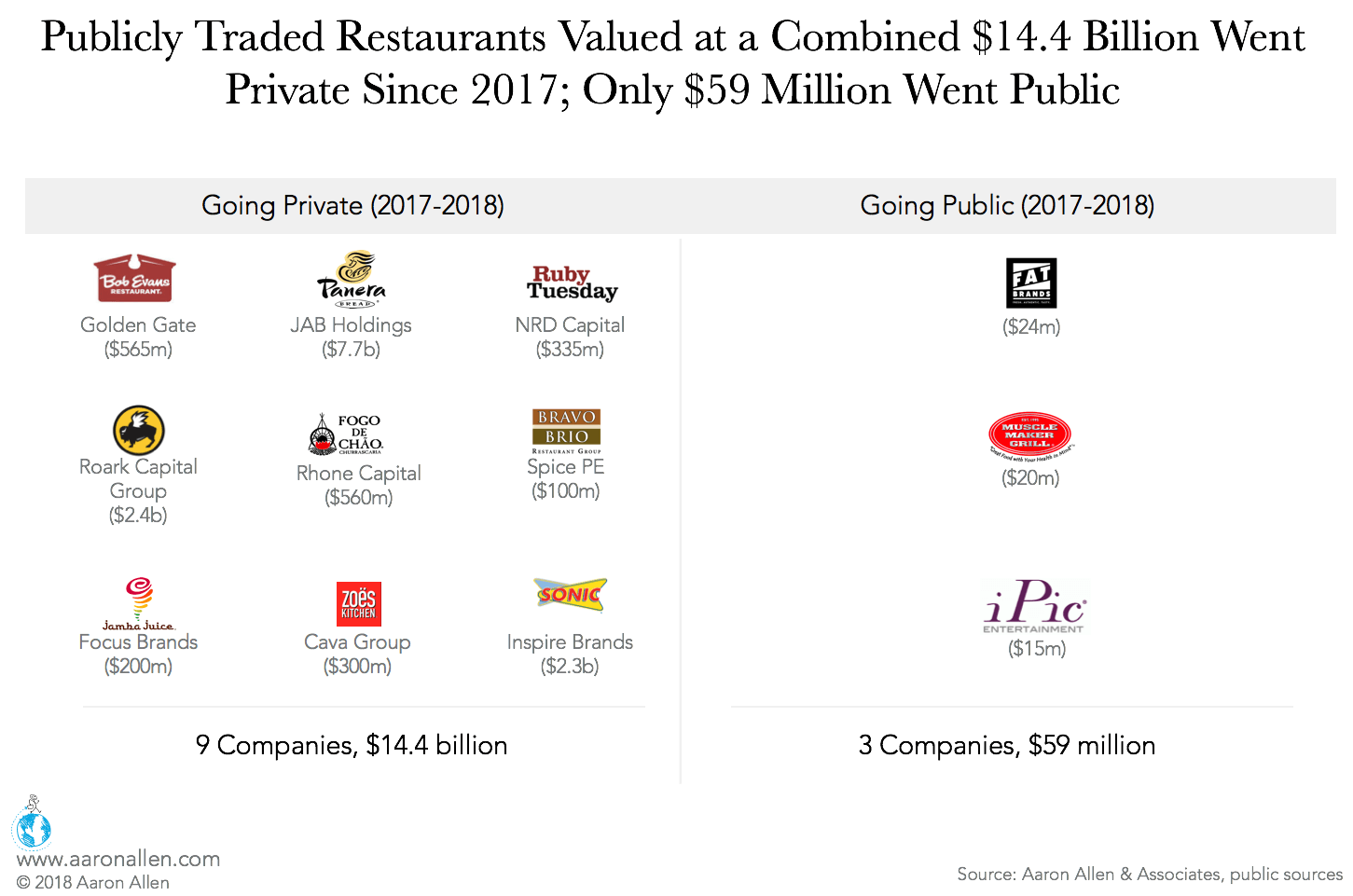

Since January 2017, nearly $15b worth of restaurant stocks in the U.S. delisted, as nine companies left public stock exchanges for private hands. The public-to-private deals come at the moment when very few restaurant companies are making initial public offerings. Over the same period, restaurant IPOs accounted for only $59m in value.

This trend isn’t isolated to the foodservice industry. The number of firms listed on U.S. stock exchanges at the end of the 2017 is less than half the number that appeared twenty years earlier.

These changes are largely due to transformations in the cost of capital: where once companies often turned to the public to fund their growth, now private money is increasingly available (and attractive) to leaders. As a result, the foodservice sector of public U.S. exchanges — home to the world’s ten largest restaurant companies — is experiencing a net loss due to public-to-private deals. Meanwhile, global IPO value and numbers have started recovering, revealing that there are still very good reasons to go public.

While Total Value and Number of Global IPOs Is Increasing, Fewer U.S. Companies Going Public

Following the 2008 financial crisis, IPOs across industries and geographies declined but have started to recover.

Over the last three years, markets have seen an average of 1,299 companies go public, 8% higher than the historical average and more than twice the 2009 number. Size is increasing as well, with the total value reaching $189b in 2017. In particular, Chinese foodservice operations are eying public markets.1

The U.S. has not seen this recovery. Between 2004 and 2007 an average of 211 companies went public each year. In 2008, that number dropped to just 31. Following a brief resurgence in 2013 and 2014, the number of initial public offerings has fallen again to an annual average of 145 companies.

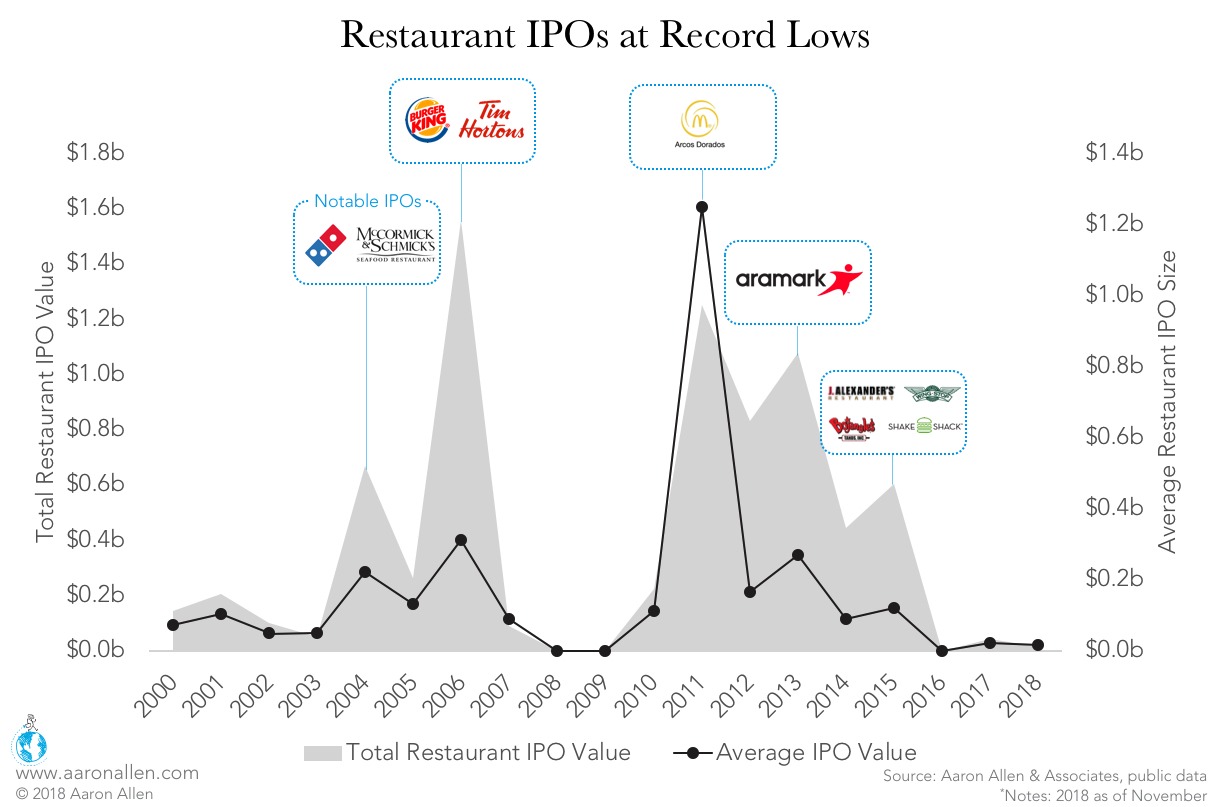

Activity in the restaurant industry follows a similar trajectory: from a peak in 2014 and 2015, IPOs among foodservice companies have largely stalled. There were none in 2016, and only two in 2017. It’s not only the number of deals that’s shrinking; it’s also the amount of capital being raised.

Aside from notable examples in 2006 (Burger King and Tim Hortons, now consolidated as the public company Restaurant Brands International) and 2011 (Arcos Dorados, Latin America’s McDonald’s franchisor), the value of shares sold in IPOs has remained below $500m in all but one year since 2014.

The Pains of Going Public: What Makes Private Capital So Attractive

With trillions in private equity capital sloshing around global markets and record-low interest rates, the pains of going public may outweigh the benefits these days. For one, IPOs are costly. They can eat up a significant percentage of the capital raised: about 15% goes to registration and underwriting costs, and companies can leave an additional 15% on the table by underpricing their shares in order to create a first-day rise in value.2

Challenges don’t stop after the company debuts: leaders must deal with intense scrutiny from a number of sources:

- Short-Term Investors: The leaders of public companies are often shackled to quarterly reports, their success imperiled by missing targets or a perception crisis that sends stocks plummeting. Many CEOs have expressed frustration with this short-term focus (most famously Ron Shaich), and a recent survey found that 77% of executives across industries believe their companies would be easier to manage if they were private.

- Short Sellers: Earlier this year, Elon Musk threatened to take Tesla private in part because of the “large numbers of people who have the incentive to attack the company,” referring to the notorious short sellers rooting for the electric car manufacturer to fail.3

- Activists: In 2017, activist investors bought more than $60b in U.S. stocks across industries, doubling the previous year. This amount of capital gives them immense power over the direction of organizations they invest in, for better and for worse. Bloomin’ Brands, Potbelly, Jack in the Box, and Fiesta Restaurant have all been engaged in disputes with activist investors.

While it’s no wonder many leaders are turning to private funding, any number of forces could influence them to undertake an IPO. Going public offers a number of benefits:

- Liquidity of Capital: One of the biggest reasons for companies to go public is to gain access to more liquid capital. Private companies, in contrast, often need to launch separate funding rounds, which can take months if not years to complete.

- Publicity: IPOs can increase brand awareness, as news of the stock offering reaches new audiences. This is especially beneficial for restaurant companies looking to finance expansion into new markets.

- Activists: They aren’t going anywhere, and that may benefit leaders of public companies. Stock prices rise around 6% in companies with these activist investors — and those gains last at least five years, according to a 2013 study.4 We need look no further than Darden for a restaurant-specific example of how engaged activists can turnaround a struggling company.

We support with both sell-side mandates and middle-market buy-side advisory for restaurant industry investments.

The “Next Chipotle” May Be a Fast-Casual, Health-Focused Brand

Leaders will always have to make calculations about how to fund the growth of their businesses. Variables change the calculus of restaurant investment decisions, both for executives and investors. Certain organizations, particularly emerging, will continue to find the benefits with regard to liquidity and publicity reason enough to go public.

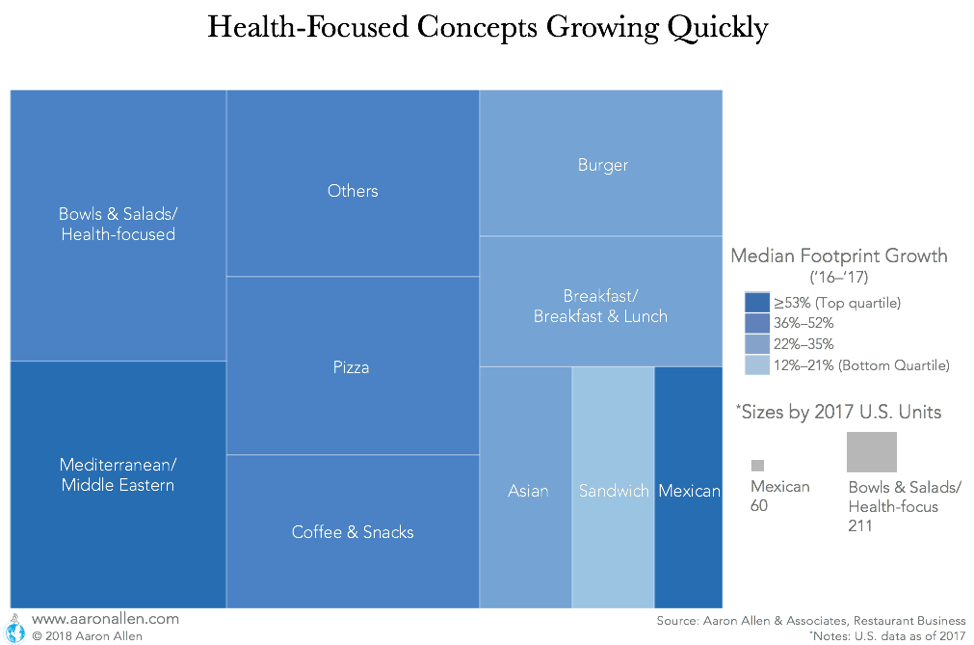

The evolution of the restaurant unit-economic model has created space for alternative formats that get a tremendous amount of consumer, media, and investor interest and appeal. These concepts are those most likely to go public, as they can rely on the goodwill (and earned media) they’ve accumulated to attract investors. A concept at the intersection of two dominant consumer trends — convenince and healthful diets — could be a contender for the next major restaurant IPO.

Already, bowl and salad concepts are increasing their footprints at a fast pace. One of these organizations may turn to public markets to fund their national (or international) growth.

Disruptive Technologies that Transform Foodservice Will Continue to Attract Investors

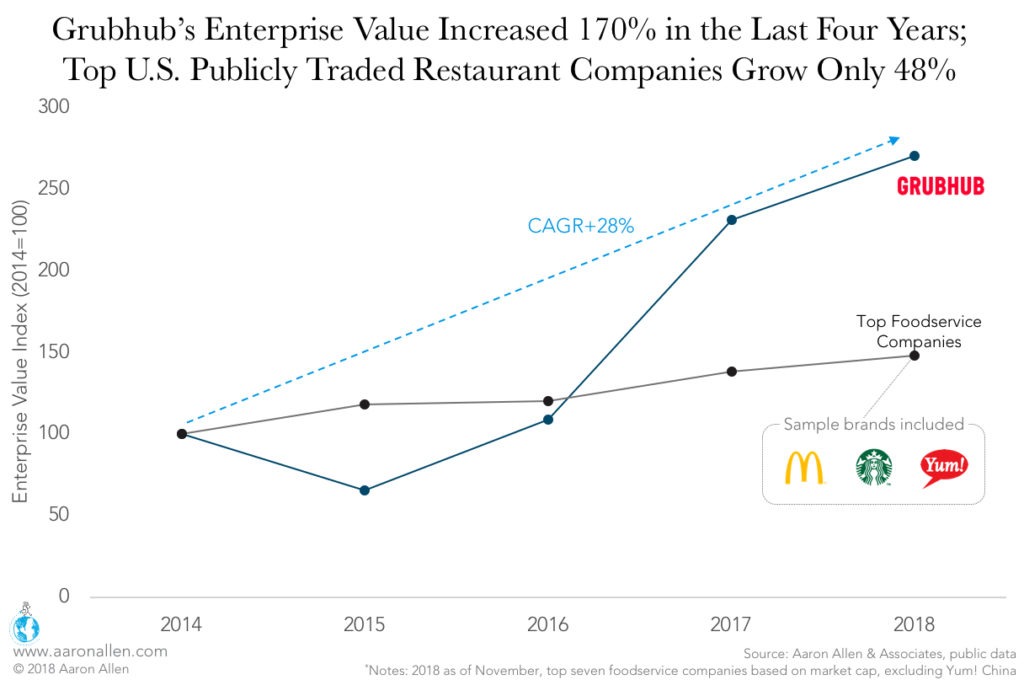

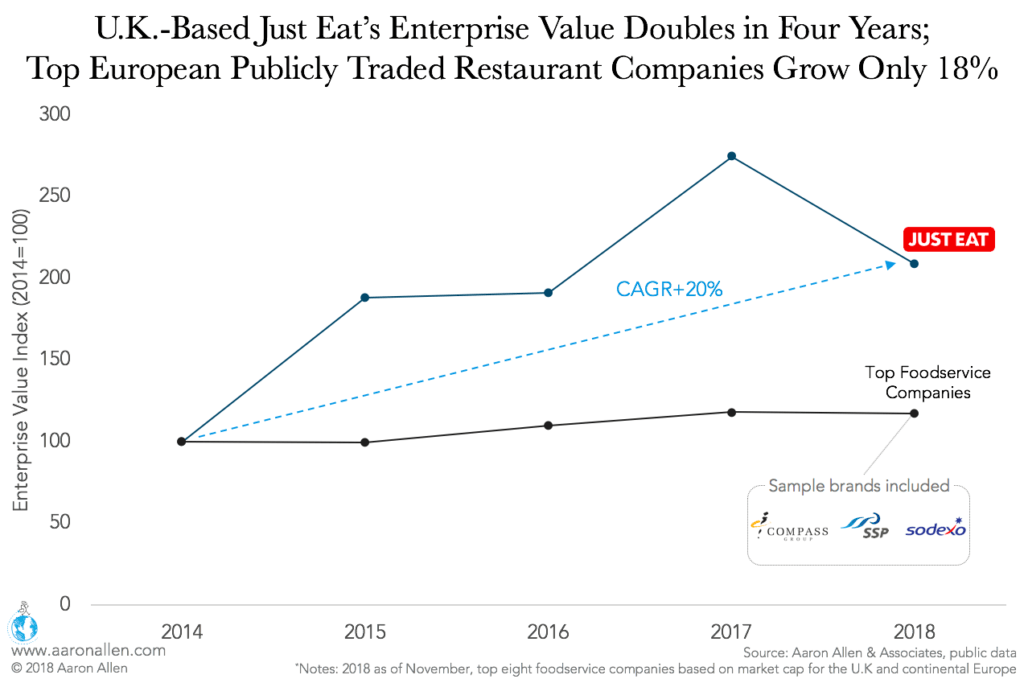

The performance of restaurant delivery companies has set the stage for large valuations for organizations whose intellectual property has the potential to reshape the industry.

Since its IPO in 2013, Grubhub’s revenue has grown at a 47.4% CAGR, and its valuation increased 70% between 2014 and 2018. Similarly, Just East, a U.K.-based delivery service, has doubled its enterprise value in the four years since its 2014 IPO.

Meanwhile, valuations for both top American and European public foodservice companies have remained steady.

These delivery companies may be the first foodservice-focused tech operations to claim high valuations on public markets, but they are certainly not the last. We can expect many more innovations over the next few years, especially in the areas of modernization and automation. The disruptive force of technology will continue to drive big IPOs, and such innovations are urgently needed in the almost $3 trillion foodservice industry.

Best Strategy Defined by Long-Term Goals

Determining how to finance growth — seeking public or private funding, maintaining corporate-owned systems or selling franchising rights, and so on — means weighing not only financial and legal considerations but also operational assumptions, variables, and preparation. The challenges of expansion, particularly cross-border efforts in which brands must translate their unique value proposition to new markets in order to win enthusiastic audiences of guests and employees, add complexity to these questions.

In these instances, external advisors armed with an understanding of historical context and the ability to more accurately predict where the industry and consumer are heading can help to find the most suitable form of funding in alignment with the company’s goals. This added competitive advantage could mean the difference between a disappointing IPO and an extended period of enterprise value enhancement.

About Aaron Allen & Associates

Aaron Allen & Associates works alongside senior executives of the world’s leading foodservice and hospitality companies to help them solve their most complex challenges and achieve their most ambitious aims, specializing in market intelligence, international expansion, commercial due diligence, and value enhancement drives for leading hospitality companies and private equity firms.

Our clients span six continents and 100+ countries, collectively posting more than $200b in revenue. Across 2,000+ engagements, we’ve worked in nearly every geography, category, cuisine, segment, operating model, ownership type, and phase of the business life cycle.

1 “Trendy Chinese Restaurant Chains Gain Appetite for IPOs,” Financial Times

2“Take this Market and Shove It,” Geoff Colvin, Fortune, May 2016

3 “Elon Musk says going private is ‘best path forward’ for Tesla,” Chris Isidore and Paul R. La Monica, CNN Business, August 7, 2018

4 “Activist Investors Are More Powerful Than Ever. Here’s What That Means For The Economy,” Dominik Breitinger and Sophie Hardach World Economic Forum, September 5, 2017

Related Content

Many restaurant executive teams are still planning with post-it notes and ballpoint pens while their competitors are harnessing theories, tools,

Even a decade after the Great Recession, restaurant commercial lending remains tight, but there’s still a tremendous amount of eager capital