Today, committing fraud is much easier — and more lucrative — than holding up a bank only to walk down the street minutes later with briefcases stuffed with $10,000 in cash. In a trade secret-intensive industry like restaurants, someone could effectively walk out of a company with some $1 million in trade secrets on a thumb drive in their pocket — faster than you can say, “Hey! That was my idea!” In a world where branding is all about being distinct, safeguarding Intellectual Property is key.

There are a slew of intellectual property issues facing the food and restaurant industry, which isn’t as strictly regulated as, say, the fashion industry. While a designer might be protected from a chain ripping off their signature handbag, a restaurant chain won’t necessarily be protected from someone trying to copy their prototype.

And restaurants are notoriously full of copycats. Some chains have tried to fight against them, though. Taco Cabana and Two Pesos famously fought their way to the Supreme Court, which ruled that Taco Cabana’s look was distinct enough that Two Pesos couldn’t copy it.

Still, the restaurant industry struggles with protections for intellectual property. Here are a few of the areas in which restaurant chains need to be especially careful of protecting their property and secrets.

The Cost of Coycats

There’s a lot of cash in counterfeiting. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, the total value of counterfeit goods imported into the U.S. or sold abroad on the low end was anywhere from $29 billion to $143 billion in 2015. A 2014 study found that the economic impact of trade secret infringement on the U.S. economy was estimated to be $180 billion – $540 billion, or roughly 1% – 3% of GDP. To put that in perspective, sales from the restaurant industry constitute roughly 4% of GDP. In other words, the cost of trade secret infringement is hefty, even when compared to the $800 billion restaurant industry.

In 2013, the Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property found that international theft of American IP causes at least $320 billion in annual economic losses to the U.S. and job losses “running into the millions.” In other words, those dollar losses are comparable to the current annual level of U.S. exports to Asia.

Of course, not all IP losses concern restaurants. But many do, and there are countless examples — not all of them blatant. The QSR industry is a mish-mash of copycats, with nearly every major chain offering nearly identical promotions: four-for-$4, five-for-$5, and on and on.

McDonald’s, for one, has ripped off a slew of its competitors offerings, though it would be tough to argue that it’s blatant copyright infringement. Over the years, the burger chain has tried its hand at tacos (a move that likely angered Taco Bell), gone head-to-head with KFC by selling fried chicken, and eventually took the plunge into McCafé coffees, thanks in large part to the success of Starbucks. Even today, McDonald’s is taking yet another page out of the Starbucks playbook, in its move to serve sustainable coffee.

Even the powerful aren’t immune. In 2016, Kimbal Musk (Elon’s brother) filed a federal lawsuit against celebrity chef Wolfgang Puck, alleging him of copyright infringement. According to the suit, Musk and Puck met to discuss Musk’s restaurant concept, The Kitchen, in 2012. The talks didn’t materialize into a partnership, though Puck unveiled his own concept (called, of course, “The Kitchen”) a couple years later. Musk’s suit alleges that the opening of Puck’s restaurant — which has a strikingly similar logo and design — “immediately caused confusion in the restaurant industry and marketplace, as people assumed that Mr. Musk has decided to affiliate with or license Wolfgang Puck.”

Branding

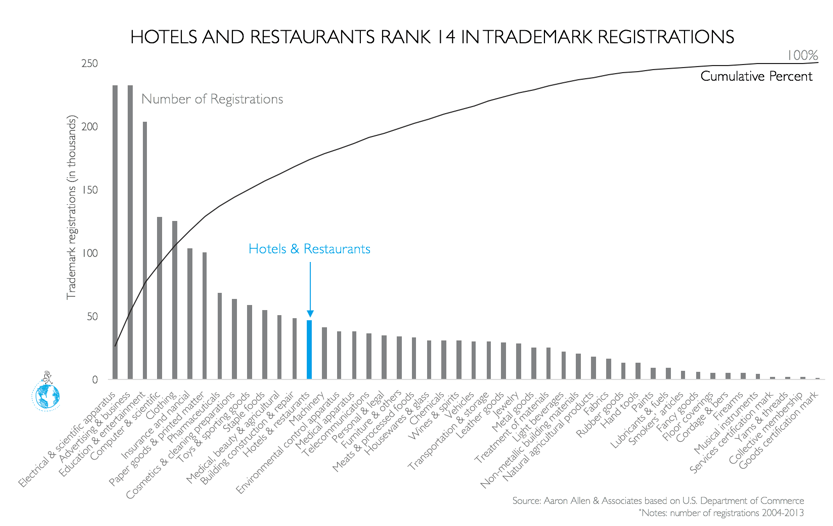

Though hotels and restaurants are not considered to be a trademark-intensive industry, the category did contribute some 2.12% of all marks registered between 2004 and 2013.

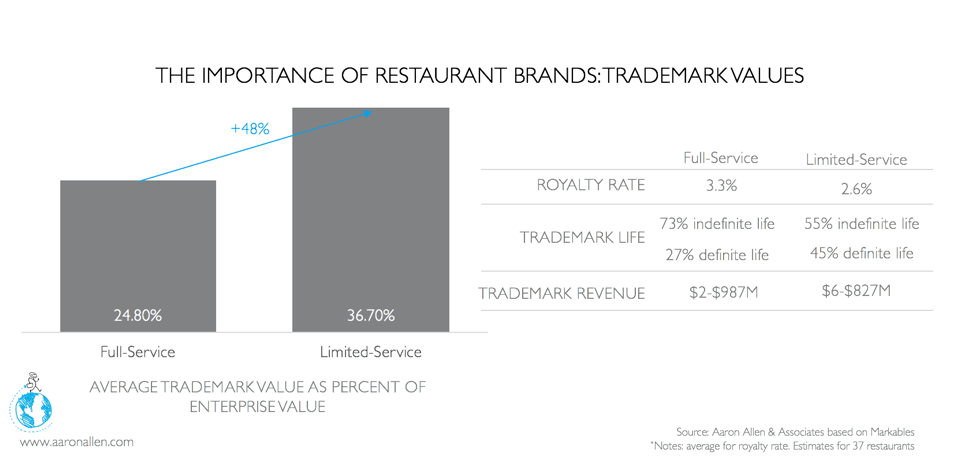

In fact, trademarks account for roughly 25% of the enterprise value of full-service restaurants and 37% of that of fast food restaurants.

Infringing on someone’s name, or logo can cause a lot of confusion in the marketplace. Just ask Chipotle, which once prided itself on being “the little guy,” standing up to the big bullies of the world. But over time, Chipotle became the bully, accused of ripping off “little guys” like Momofuku with its fast-casual Asian concept, ShopHouse Kitchen. The irony of Chipotle’s announcement that it would close all ShopHouse outlets in March 2017 was likely not lost on Momofuku, nor on the legions of others who have accused Chipotle of copycatting.

Case in point: Chipotle’s new better burger concept, which it first attempted to trademark (under the name “Better Burger”) in 2016. Less than two months after it filed to trademark the name, Chipotle abandoned that trademark, saying it had been challenged. Eventually, the chain decided on Tasty Made for its new concept — though that name (and logo) have since been challenged by another fast-casual burger joint, called Tasty Burger.

Despite all the accusations of copycatting, Chipotle itself has fought against those who try to so much as use the word “chipotle.” We certainly haven’t been impressed by the fact that Chipotle (arguably the biggest player in the QSR industry) rails against the big guys, but in many ways has itself become one.

Recipes, Flavors, & A Distinct

While a brand name or menu item name can be trademarked, recipes or cooking techniques cannot (sound trademarks, like restaurant jingles, are also difficult to protect). Thus, items like the exact blend of spices in a fried chicken breading, or the exact amount of the ingredients found in a bottle of Coca-Cola remain part of a restaurant’s trade secrets. It is therefore essential to keep them just that – a secret. Rumor has it that the exact recipe for Coca-Cola is kept literally under lock and key — some even say the recipe for the world’s most famous soda is actually divided into bits and pieces, and kept in numerous locations. That flavor is distinctly Coca-Cola — while others have tried, none have quite measured it.

If you’ve seen Coming to America, you’re well aware of the confusion — and hilarity — that can result from a knock off. The film’s “McDowell’s” was, for all intents and purposes, a McDonald’s, just with a slightly different trademark.

Trademark protections have helped some ensure their special recipes and designs can’t be ripped off. Dominique Ansel, the maker of the Cronut, (or should we say Cronut ™) applied for federal protection for the name of his croissant-donut hybrid. While it didn’t prevent bigger players from ripping the pastry off, it did force them to answer for it — though Dunkin’ likely backed off for public perception rather than not wanting to fight legal battle. After all, what brand would want to be known as the company that crushed the Cronut? Bankrolls might be able to win legal battles, but they can destroy creativity in the process.

After Dunkin’ Donuts announced its plans to release its own limited edition croissant-doughnut hybrid, the chain was forced to sue the more generic name, “croissant doughnut.” But interestingly, Dunkin’ was also required to answer questions about its pastry different from the Cronut. All in all, a pretty strong win for Ansel and those who want to ensure their intellectual property remains protected.

In the Restaurant Industry, Originality is Key

Scientists have found that between 10 and 20% of the brain is comprised of “mirror neurons,” making copying others a natural instinct. Of course, so is greed and selfishness, but that doesn’t mean it serves everyone well. Copycats almost always go out of business before the original – but not without inflicting some damage first — and few wants to be (or buy from) a knock-off unless “cheaper” is the primary motivation. That being said, uniqueness and originality trump a cheap copy any day of the week.

There are more than 18 million restaurants in the world – those that aren’t distinct are the most likely to go extinct. Restaurant concepts should be so distinct that those who try to copy them would be immediately identified as a copycat. If you blindfolded a customer and had them walk into a restaurant, would they know it’s yours right away?

Intellectual property rights play a pivotal role in the commercial value of every successful restaurant brand. Copying a restaurant’s best-selling sandwich might not seem as criminal an act as walking out of a bank with a suitcase full of cash, but for restaurants, bread and butter is (quite literally) the bread and butter of the company. The same goes for a chain’s look, logo, and promotions. In an industry full of lookalikes, originality is sacred. Protecting that uniqueness, and ensuring it isn’t watered-down by copycats, is therefore key to preserving the value and quality of a restaurant brand.

* * *

About Aaron Allen & Associates

Aaron Allen & Associates is a leading global restaurant industry consultancy specializing in growth strategy, marketing, branding, and commercial due diligence for emerging restaurant chains and prestigious private equity firms. Aaron has personally lead boots-on-the-ground assignments in 68 countries. Collectively, his clients around the globe generate over $100 billion annually and span six continents and more than 100 countries.