Any pizzeria owner or chain executives who keeps up with the business news is likely more than a little green with envy (by now, probably emerald). The reason: Domino’s is killing it online.

While over 75% of the US restaurant industry is still struggling to get its act together and launch an app that actually works, Domino’s has leapfrogged the competition, flaunting collaborations with some of the most game-changing tech innovations (Domino’s now supports orders from the Amazon Echo and Apple Watch). These new initiatives make its emoji-enabled ordering by tweet or by text look like a gimmick.

The pizza chain’s been-there-done-that-what’s-next attitude toward tech means that 60% of its revenue (something to the tune of $2 billion system-wide sales in the US) comes through digital channels. Average franchisee same-store sales growth averaging over 10% from 2015 to 2018. CEO Patrick Doyle has also claimed that, in terms of transaction counts, Domino’s is competing with the likes of Amazon and Apple, ranking among the world’s top five online retailers.

Domino’s ahead-of-the-game adaptations of digital convenience engineering have gotten to the point where the company will soon make ordering from its website obsolete. But the company is not blowing its competition out of the water simply because it was an early adaptor of digital integration. There’s plenty more to it.

ONE OF THE BIGGEST ONLINE RETAILERS? THAT SOUNDS FAMILIAR.

In January 2008, Domino’s launched its Pizza Tracker web system — an online application that allowed guests to keep tabs on the progress of their order with a 40-second accuracy margin.

Prior to launching Pizza Tracker, Domino’s saw less than 15% of its sales from online orders; with the new system, the website started generating 20% of company sales — a “win” from any perspective.

Domino’s bet big; it launched one of the best digital ordering systems the industry had ever seen. Pizza Tracker boosted online ordering profits by 23% because online guests spent, on average, $2 more than those who ordered over the phone or in person.

It also made the pizza chain the fourth-largest e-retailer in 2010 (to be fair, the competition back then consisted of Amazon, Staples, and Office Depot).

And yet, in 2008, Domino’s stock was still selling for less than $3 per share, and company same-store sales in the U.S. fell 4.9% system-wide, with franchise stores seeing an even worse 5.2% decrease. These figures were seven times worse than the industry average. While in 2008 and 2009 the US pizza industry saw 1.3% and 2.5% unit growth, respectively, between 2008 and 2009 Domino’s closed 120 domestic units.

Convenience engineering can only go so far. If product quality and other elements of the guest experience are compromised, no one will order — no matter how easy it is. A question posed in a January 2008 Gizmodo article about Pizza Tracker summed this up well.

The answer, according to the sales figures, was no.

GOOD MARKETING KILLS DYING BRANDS FASTER

The story of the Domino’s Pizza Tracker illustrates a hard truth: great marketing will only kill a bad operation faster. And, at the time, Domino’s wasn’t just wounded, it was hemorrhaging.

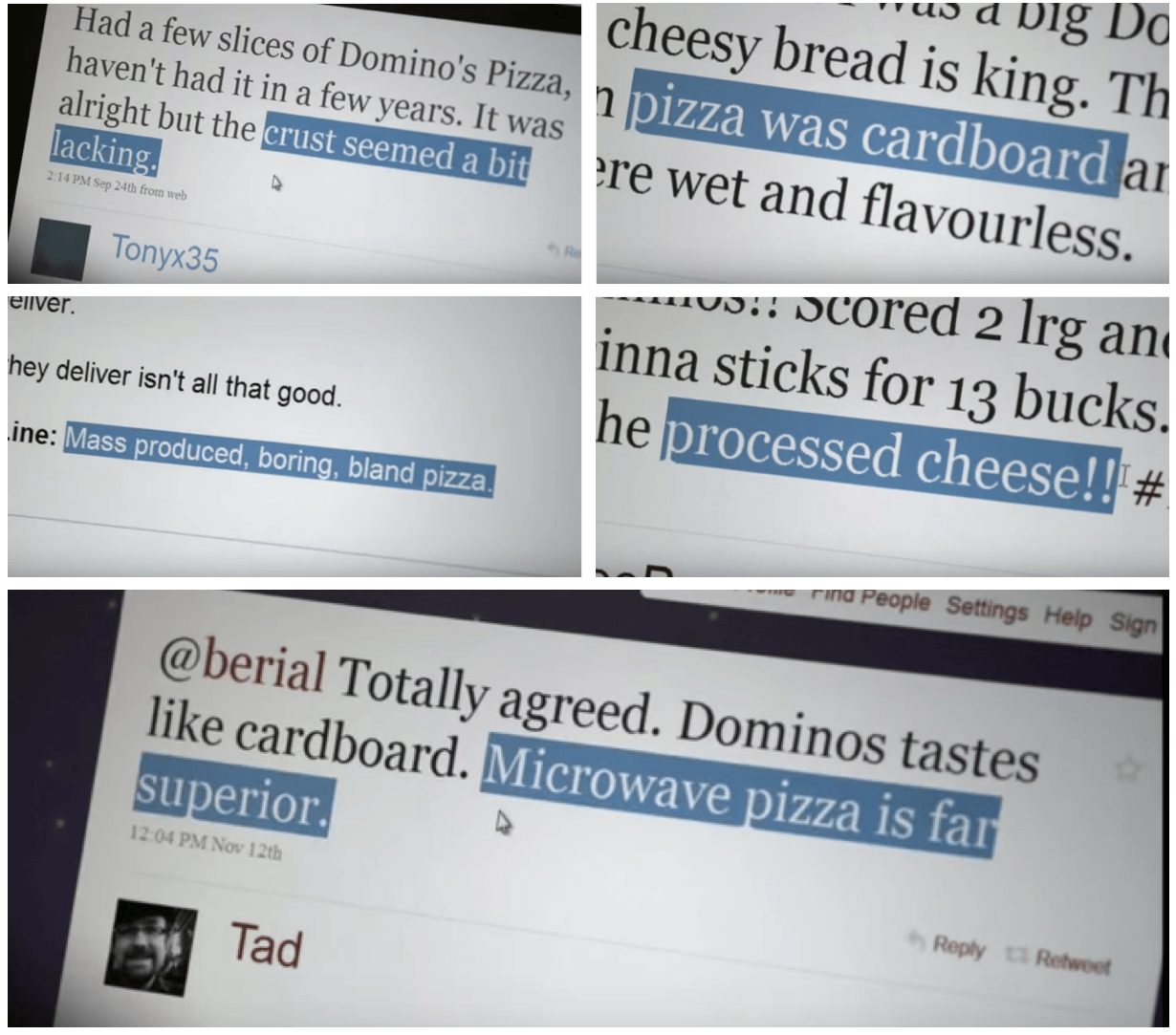

A few screenshots of customer comments (pulled from the first ten seconds of the company’s comeback ad) paint a pretty vivid picture of just how bad the problems were:

By April 2009, Domino’s poor product perceptions had positioned the brand as a house of cards, ready to topple if someone as much as sneezed. Unfortunately, lots of employees did, all over customers’ orders.

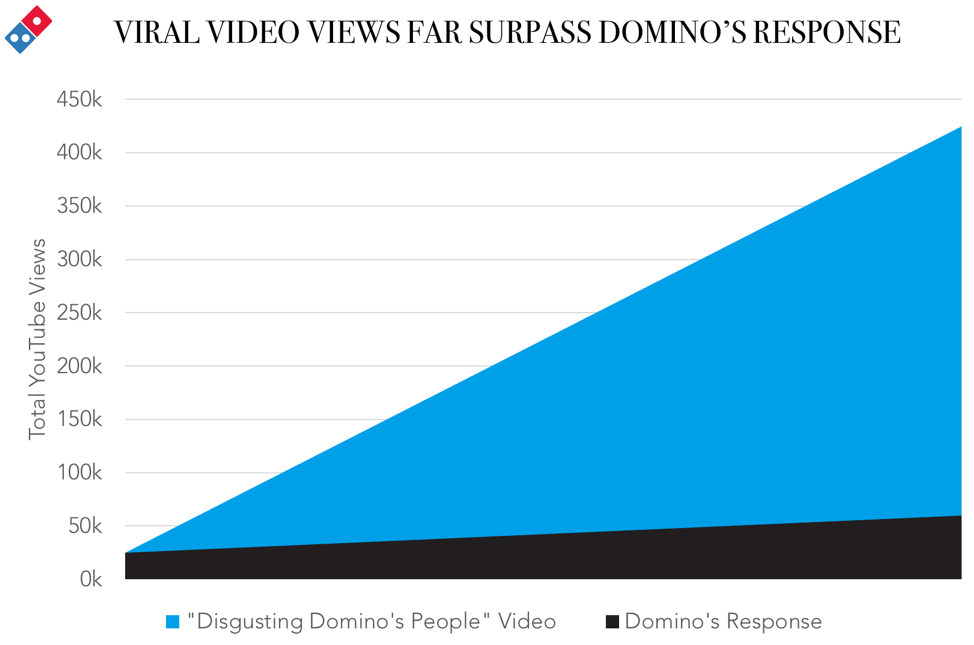

When videos of Domino’s employees doing unspeakable things to the product went viral, the company tried to handle the situation, posting their own YouTube video, in which CEO Patrick Doyle called the whole thing a “hoax.”

But the painful reality was that viewers had lost all confidence in the brand. Domino’s crisis communications was too little, too late. The video showing the health-code violation had nearly eight times the views as the company’s response.

In just about 24 hours, Domino’s public perception plummeted. According to BrandIndex, the company’s “buzz ranking” (a score that ranges from 100 to -100, tracking positive and negative sentiment) dropped from 22.5 to 13.6 in less than a week. Even though the company’s PR team knew about the video with 45 minutes of it being posted, same-store sales plummeted, falling from roughly 1.0% in Q1-2009 to -0.7% in Q2 and flat (0%) in Q3.

TIME FOR A TURNAROUND

Everything had gone wrong for Domino’s: an unpopular product, a food-safety scandal, and a mishandled crisis response team. Fortunately, it got its turnaround campaign exactly right.

The company didn’t make excuses. It didn’t discount. It didn’t compare itself to competitors. It didn’t promise to be faster. It recognized that it was leading the way in delivery for all the wrong reasons, living up to its promise of pizza at your door in under 30 minutes by sacrificing quality (frozen, canned ingredients that left the crust tasting like cardboard) and sometimes even its drivers’ safety.

In December 2009, Domino’s apologized. And it got to work.

Everyone remembers the 2010 ad campaign nicknamed “Our Pizza Sucks.” Rather than ignoring the negative commentary, Domino’s fully embraced it (even displaying instant reviews on a marquee in Times Square — imagine having your criticisms advertised to hundreds of thousands each day).

In Q1 2010, the company saw a 14.3% increase in revenue over the previous quarter. From December 2009 to December 2010, Domino’s stock shot up 130%. By 2010, domestic same-store sales were up 10.3%, a near-10 percentage point increase over 2009.

Domino’s stock has since reached 89x higher than pre-turnaround levels (with a low of $2.83 per share and topping out at $252+ per share in May 2018) thanks to an epic campaign that generated over one billion free PR impressions — earned media that pays big dividends.

Thanks to continued investment in technology and a commitment to executing on its core competencies, Domino’s has continued to see same-store sales increase consistently. It’s officially overtaken Pizza Hut as the world’s largest pizza chain (the leading delivery player, and in second place for carryout orders).

What’s more, Domino’s invested in its people. Following the turnaround, Doyle reported that 90% of the brand’s hourly workers turn a position at Domino’s into a full-time career path. On top of the fact that engaged associates are more profitable team members, a statistic like this also goes miles in ensuring there will be no more booger-lover pizzas served.

GOING FOR GOLD

Even when Domino’s was in the thick of its perception crisis, it still ranked as the second pizza chain in the US (seeing $3 billion in system-wide revenue in 2009 compared to Pizza Hut’s $5 billion).

Since its 2010 turnaround, Domino’s has brought its tech team in-house (as of 2018, more than half of Domino’s team members at the world headquarters are technologists or others with an analytical focus, according to Jeffrey D. Lawrence, the company’s CFO and EVP), taking full responsibility for the development of its app and website. This investment has been paying off.

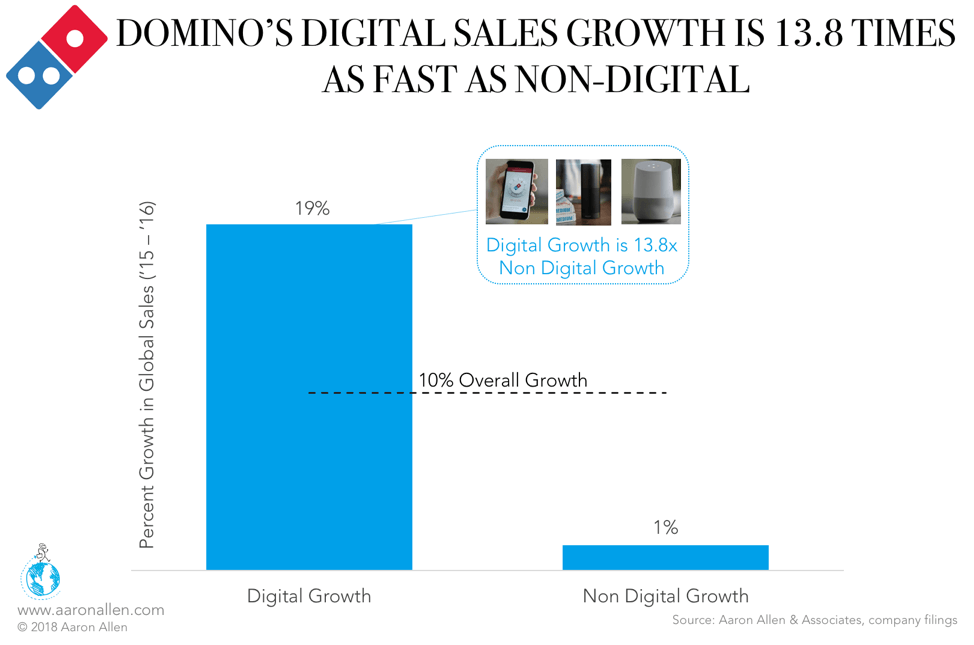

Over 60% of Domino’s orders now come from digital channels. Back in 2011 when the company launched its iPhone app, it took 28 days to see $1 million in sales. Three months after the release, the Domino’s app was seeing $1 million in sales each week.

From 2015 to 2016, system-wide sales for Domino’s grew 10%, overall. Nearly all of this growth was attributable to digital sales (web, mobile, and other less traditional channels such as the Echo or Twitter orders), with a 19% increase. Non-digital sales (phone-in orders or ordering at the store directly) only contributed a 1% growth.

Domino’s proves that you can never make it too easy for customers to buy from you. It has also shown that R&D can pay off handsomely. It’s an inspiring story, and other chain operations should take it to heart.

But rather than try to copy Domino’s success by developing their own iPhone, Alexa, and Echo apps, they should consider how digital channels can be leveraged to extend their specific brand promise. Domino’s convenience-focused tech suits a brand known for fast delivery, but it wouldn’t make sense for a fine-dining establishment that built its reputation on superior service and ambiance.

Any restaurant looking to make a turnaround should consider how technology can fit into its operations — as long as it doesn’t forget the qualities that keep its customers coming back again and again.

ABOUT AARON ALLEN & ASSOCIATES

Aaron Allen & Associates is a leading global restaurant industry consultancy specializing in growth strategy, marketing, branding, and commercial due diligence for emerging and established restaurant chains and prestigious private equity firms. We help restaurant operators and investors make informed decisions, minimize risk, and maximize sustainable value. With experience on both the buy- and sell-sides of transactions, we have a robust understanding of trends and factors impacting restaurant chains and private equity funds around the world. We help protect, enhance, and unlock value throughout every phase of the investment lifecycle. Collectively, our clients post more than $200 billion in annual sales, span all 6 inhabited continents and 100+ countries, with tens of thousands of locations.