Amazon founder Jeff Bezos made headlines in June 2016, when he announced the e-commerce giant would invest $3 billion into India, citing the region’s “huge potential.” That this came on the heels of the company’s 2014, $2 billion infusion, was big news. While Apple’s Tim Cook once said India is where China was “maybe seven to ten years ago,” Bezos sees something else: an entirely different market, one with a lot of untapped potential that’s growing at a rapid pace.

Bezos isn’t the only one to notice that India presents a significant opportunity. With so many changes taking place in both the industry and the region at large, restaurant chains that can utilize what has been learned and developed in the more competitive and mature foodservice industry of the Western world will find themselves at a considerable advantage.

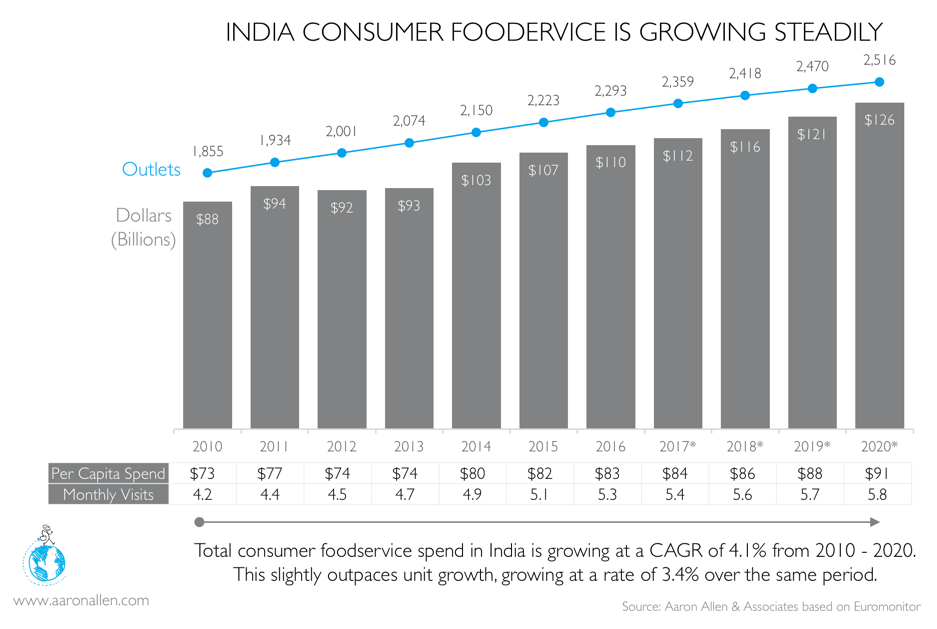

More Indians are slowly warming up to the idea of eating in restaurants, and not just for special occasions. Thanks to growing wages, urbanization and technology’s influence on consumption habits, foodservice sales in this country of USD 1.3 billion are growing at about 10% annually (making it one of the fastest-growing in the world). This growth is double the rate expected for the much more mature U.S. restaurant industry, and with a population quadruple the size. All told, between 2013 and 2021, the Indian restaurant market is projected to double.

For private equity firms and global restaurant brands, India represents huge upside potential, especially as major Middle East markets, which are undergoing rapid growth now, approach saturation levels in the years to come. And as the competition in India heats up, home-grown Indian operators will need to raise their game if they want to stay in the race.

WHY INDIA?

Many separate forces are at work in creating huge potential for restaurants in India. Its economy is among the fastest growing in the developing world; the International Monetary Fund projects the country’s annual GDP will increase by 7.4% through 2017 and 2018 — more than double the world average.

India is also one of the largest consumer markets globally, and one of the youngest with more than 45% of the population under 25 years old. For teens and young adults, eating out is a popular form of socializing, contributing to the growth of multiple segments within the expanding market.

Disposable income is on the rise; the educated middle class is growing; and as the country grows more industrialized and cements its reputation as an IT hub, per capita income stands to grow as well. According to data from the Economist Intelligence Unit, personal disposable income should grow about 10.5% annually through 2020.

India’s traditional close-knit extended families are less common; as younger family members move away for education and jobs, they are setting up smaller households, making dining out more attractive. More women are joining the workforce as well, especially in urban areas, leaving less time for home cooking and creating more demand for dining out/takeout options. We’ve seen similar spending trends in the U.S. though it’s worth noting that this will occur on an accelerated time frame in India (as Western systems have already been developed, they now only need to be implemented in other parts of the world, like India).

Mobile usage, satellite TV and greater access to the Internet is connecting more Indians with the world outside India and internally. Indians have very strong food traditions, and social media has offered another platform to compare notes on food trends and hot new restaurants.

Travel within and to India is on the rise. According to India’s Ministry of Tourism, in 2015 the country welcomed 8 million visitors, a figure that is expected to nearly double by 2025. This isn’t quite as high as other burgeoning parts of the globe (Dubai saw 14.2 million tourists in 2015), but significant nonetheless.

The government’s Make in India campaign, launched in 2015, is designed to create 100 million manufacturing jobs by 2022 through incentives for manufacturers. If it succeeds even partially, it could mean more discretionary income for more Indians.

DIVIDING A VERY LARGE PIE

In India, full-service restaurants command the largest market share, at 57% of sales. The next biggest category is QSR, at about 16%.

Considering the country’s giant patchwork of cultures and cuisines, it’s probably not surprising that about two-thirds of the restaurant units are loosely structured, small, independent eateries—referred to as “unorganized”—that often double as retail food stores. Only about two% of the total inventory of restaurants is branded—less than a tenth of what’s seen in other countries with a more established foodservice industry.

But that’s changing. As international, national, and regional players move into the market the momentum is shifting toward more chain-affiliated and standardized operations. A value-seeking mentality (to be expected, with median household income around USD 4,000 in 2015), marketing, greater mobility, and social media will all fuel more demand for QSRs.

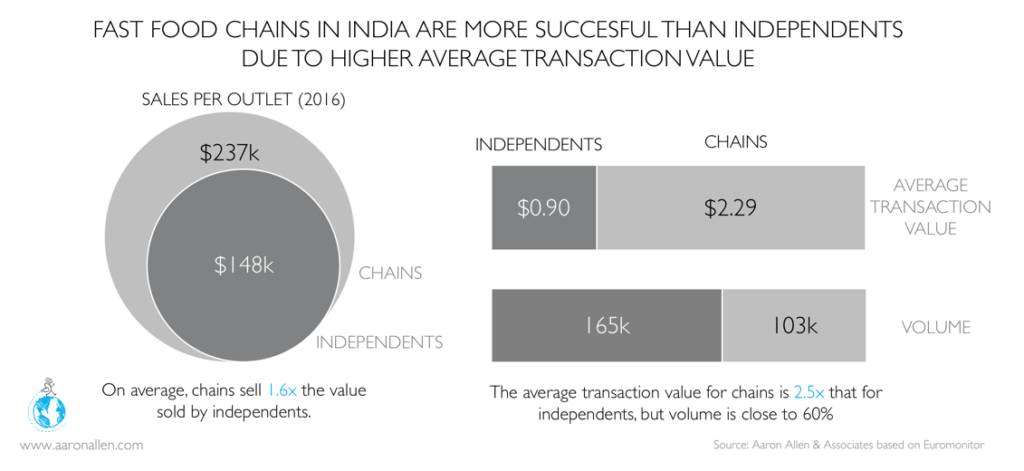

Within fast food, chains are outperforming smaller operators in India. Chain-affiliated QSRs ring up higher sales per outlet than independents, with chain transactions averaging USD 2.29 vs. USD 0.90 at independents. Many home-grown operators will need to modernize and standardize their operations if they want to stay competitive as the market heats up.

More than 60 foreign restaurant brands operate in India. Indian-based brands include Natural, Dosa Plaza, Jumbo King and Cocoberry; major U.S. players include McDonald’s, KFC, Subway, Domino’s, Pizza Hut, Dunkin’ Donuts and Starbucks. Jubilant Foodworks, reportedly India’s largest and fastest growing foodservice operator, has more than 1,100 Domino’s in 260 cities and nearly 70 Dunkin’ stores.

Geographically, the prime opportunities are in the urban centers, where higher wages are attracting more Indians. By 2020, it’s estimated that 36% of India’s population will be urban dwellers, up from 32% currently.

MANY OPPORTUNITIES, BUT WITH CAVEATS

In the World Bank’s 2017 Doing Business rankings – which compare the climate of emerging economies — India scored very low in a number of categories, from starting a business to construction permits, registering property, taxes, resolving insolvency and enforcing contracts. Not surprisingly, given that government bureaucracy is the norm, corruption has long been a characteristic of Indian society.

Despite that, private equity investors see the upside potential of this huge market (similarly, PE deals are already making their mark throughout the Middle East restaurant industry). Between 2011 and August 2016, they made some 80 deals totaling more than USD 640 million for Indian restaurant development.

International brands operating in the region are still learning the cultural and culinary nuances of doing business in India (many of which are similar to the challenges facing restaurant operators in the Middle East). McDonald’s, for example, reportedly adjusted 70% of its menu to include items like the Veg Maharaja Mac, a plant-based version of the popular Big Mac. Dunkin’ Donuts broadened its scope beyond the signature donuts and coffee to include sandwiches, and created more of an all-day menu—because Indians don’t eat donuts for breakfast. Nando’s, which opened its first three Indian franchise units, closing them two years later, returned in 2012, revising its QSR model to a larger footprint with table service and introducing vegetarian versions for 40% of its menu items. Customers of the original locations considered the price points more in line with FSR than QSR.

COMPETITIVENESS REQUIRES CREATIVITY

Labor is cheap in India, but the labor force is also largely unskilled, so automated processes and simple-to-prepare QSR-style menus can help ensure quality and a consistent product. Real estate is relatively expensive in India, and with an emerging economy that situation is only likely to escalate. So creative strategies, such as operating kitchens in lower-rent districts, are needed to stay competitive.

The tax code, which has been overly complicated, could be simplified this year with the planned implementation of a simplified national Goods and Services Tax (GST) that would replace individual state taxes. If that happens, it will streamline transportation and reduce some logistical costs of doing business. And the inadequate transportation infrastructure—and legendary traffic jams—can present interesting logistical challenges that require innovative solutions, especially if fresh food is involved.

Just because something works in one part of the world doesn’t necessarily bode well for success elsewhere. Regional operators who can face the above challenges head on, and address them appropriately — by utilizing an in-depth knowledge of the country’s unique challenges from those within or outside of the organization — will boost the odds of improving company performance. Overall, with the right approach and understanding of the market, the potential for return on investment in India remains huge.

* * *

ABOUT AARON ALLEN & ASSOCIATES:

Aaron Allen & Associates is a leading global restaurant industry consultancy specializing in growth strategy, marketing, branding, commercial due diligence for emerging restaurant chains and prestigious private equity firms. Aaron has personally lead boots-on-the-ground assignments in 68 countries. Collectively, his clients around the globe generate over $100 billion annually and span six continents and more than 100 countries.