One of the most common restaurant start-up mistakes is underestimating the capital budget requirements involved in opening a restaurant. And one of the most common questions we’re asked is: “How much does it cost to open a restaurant?”

Here, we hope to provide some rules of thumb and average costs and ranges, as well as identify common hidden costs that can be the cause of not only headaches and budget shortfalls, but that also contribute to restaurant fatality rates.

Delays in opening from complications with permitting, scheduling, hiring, improperly estimating lead times on equipment and delivery, sequencing of build-out and installation can all contribute to additional costs. And the burn-rate on cash (between rent, management, line-level employees, utilities, and the cost of capital) can quickly drain and deplete the budgets before the restaurant is even opened.

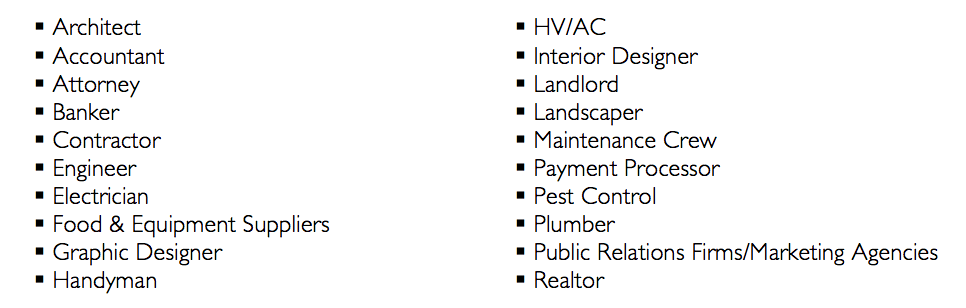

When planning to open, a restaurateur has to find, screen, hire, enroll/inform, manage, and maintain relationships with an army of help including a minimum of the following specialized disciplines:

The average restaurant could easily have 100+ different supplier companies and active accounts. For every one of the items in the list above, restaurateurs can be paying anywhere from $100 a month to $800 an hour. And that’s before all of the free accounts that need to be managed, like Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Vine, Google+, TripAdvisor, Yelp! and whatever else is hot-button (not to mention the countless trade publication subscriptions to be keeping up with). Brilliant restaurant strategy requires blending the art and science combined with impeccable preparation, skill, and timing.

SO WHAT IS THE COST TO OPEN A RESTAURANT?

Naturally, costs and revenues vary by category, concept, cuisine, geography, and the economies of the business and entrepreneur. Typical restaurant build-out costs range between $150 – $750 per square foot, depending on the quality of materials used, construction costs, and other factors. The total investment (excluding land and soft costs) usually ranges between $250,000 – $2.5 million, and the average size ranges between 1,200 – 10,000 square feet.

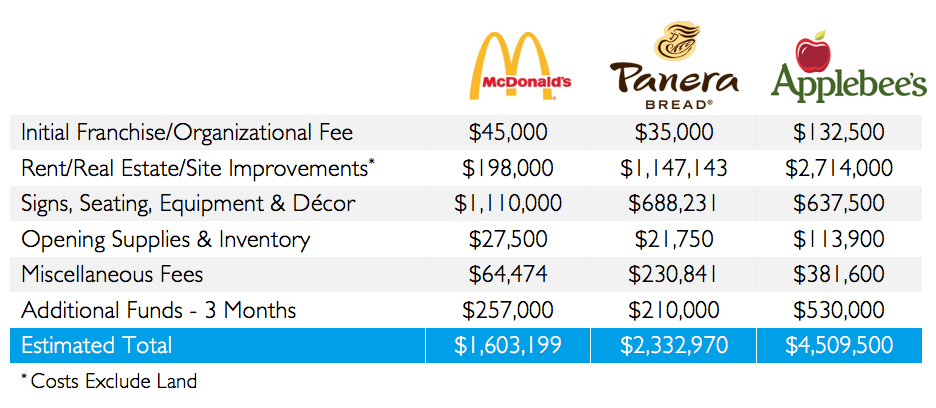

Here are some averages for major restaurant companies, and the distribution of their opening costs.

The average restaurant operates with sales per square foot of $513.70. The average cost to build of $404 per square foot includes just the build-out cost. Some of the other costs that often go underestimated (or in the worst cases, forgotten) include the following items (and hundreds more scattered across more than a dozen cost categories).

FURNITURE, FIXTURES & EQUIPMENT

Typically, 30–40% of the total hard cost budget is allocated to furniture, fixtures and equipment (FF&E), with the rest of the budget being distributed among construction/leasehold improvements (40–60%) and contingency (10–15%). On average, 10–20% of the total FF&E costs is allocated to design and architecture fees.

As an example, a decent commercial chair is going to cost at least $80 (in most cases). In a luxury restaurant, it wouldn’t be unheard of to see those as high as $800. That multiplied out by a 100 seat restaurant adds up very quickly.

MENUS

Printed menus can range from only about $5 each from the local print shop, to as much as $300 per menu with sturdy binding and intricate inlays. Assuming a 200-seat restaurant (a good rule of thumb is to order 1.5 times menus as there are seats), that could be close to $90,000 in menu printing costs (which will have to be replaced periodically, too).

This is one of the contributing factors as to why you don’t see a lot of fine dining restaurant chains – as those expenses are better suited for one-off restaurants and the celebrity-chef features in high-end markets. It’s also a reason why the trend of investment in restaurants is geared more toward fast-casual concepts and those that have lower capital requirements and higher sales to investment ratios.

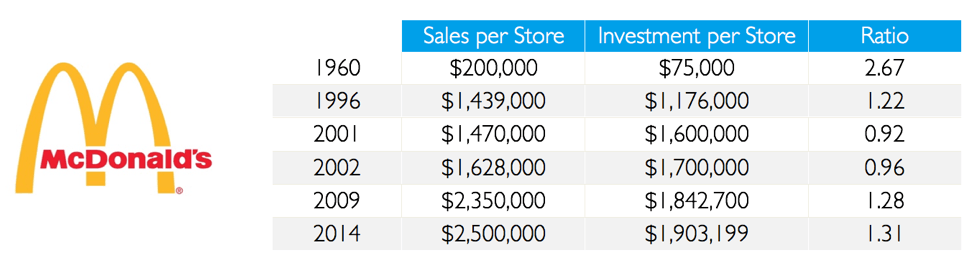

Sales-to-investment ratio is a key metric for investors when considering opening a restaurant. Here’s a quick overview of McDonald’s sales to investment performance over time.

PRE-OPENING EXPENSES

To develop all of the recipes for testing, either a temporary kitchen or rented equipment will be required – how else could the menu be developed and properly tested, if not on the actual equipment set up? And while a chef won’t fail in the development of each new menu item as much as Thomas Edison did when inventing the light bulb, rest assured he won’t get it right on the first try. Money in inventory is necessary before selling any food just to get the menu perfected.

Restaurants are in cash-burn situation for months (or up to years, if not executed properly). Before a dollar can be collected in revenue, a considerable sum will be spent in capitalized operating expenses. Expect at least a few months’ worth of pre-opening rent, labor, and utilities. But this can also get tricky, as we’ve seen unexpected delays for operators that can push back openings by an extra four to six months, easily. That might not sound like much, but on a percentage basis for the pre-opening expenses budget, it can be an increase of as much as 300%.

Grand opening expenses would also fall in this category. While an opening can cost as little as a balloon and some ribbon out front to let customers know the restaurant is open, we’ve also helped support restaurants who had dedicated grand opening budgets of more than $100,000 (granted, most restaurants also don’t need $1 million in Venini glass separating the restrooms, either). Usually, for the first year of operation we recommend a marketing budget of 6% of anticipated sales. Of that budget, 30% is recommended to be allocated to pre-opening marketing.

TECHNOLOGY

Increasingly in the modern age, technology is being utilized in an enhanced capacity for not only marketing but also greater efficiency (i.e., replacement of labor), convenience, and increasing analytics and visibility into the business performance. Technology in restaurants can take on many forms, including:

- WEB SITE: A website can be anywhere from free (on sites like wix.com for the do-it-yourselfer) to $350K+, depending on integrations with other technology (back-end functionality for on-line ordering, social engagement, mobile, etc.), the agency that builds it, and other costs required to get people to visit in the first place. Depending on the type of concept, some of these investments relate to a competitive advantage in not just marketing but operational capabilities as well.

- POINT OF SALE SYSTEM: A point of sale system (POS) could be anywhere from a cloud-based, tablet-style system for as little as $99 per month, up to Legacy POS installations which can go as high as $50,000 – $60,000 per location (and need to be updated or replaced every 5 – 7 years).

- DEPENDING ON THE STYLE OF CONCEPT: Additional technology investments may be necessary, depending on the type of restaurant being opened. Everything from ERP Systems to revenue management software to digital menu boards can fall into this category.

For these items, cost is not driven solely by the hard cost of acquiring and installing these technologies, often – more substantially – it’s driven by the soft cost of skilled and experienced internal personnel or external experts who help properly define the business and technical requirements and guide and ensure proper implementation, execution, monitoring, and reporting.

Just as the fryer does most of the work during the cooking process, there still needs to be someone there to push the buttons (meaning that, with almost everything going in, it’s driven by people, process, and intellectual property – whether that is cheap, valuable, bought, or rented).

TIMING, TECHNICAL REQUIREMENTS, AND KNOWING WHAT TO DO WHEN DEVELOPING A BUSINESS PLAN

A business plan is all too often either an afterthought or conjures up the mental image of a clunky fill-in-the-blank form on the Internet or an antiquated piece of software that asks you questions like “What is your Vision?” or prompts about writing your Mission Statement (which are almost inevitably filled in with something generic and uninspired, along the lines of “to offer good food, good service, good atmosphere”).

Many operators gloss over it and skip to the financial tables in the appendix. But all of the items listed in this article, and the hundreds (if not thousands) more details that go into opening a restaurant will have a (hard or soft) cost that is often missed or skipped. These costs need to be considered in the business planning process before any heavy investments are made in other capital costs.

UNDERESTIMATION OF SOFT COSTS

The biggest shortfall in the budgets often relate to the soft costs of development. Even some of the most experienced operators who have opened dozens or hundreds of restaurant locations are often at a loss for words when asked: “How much does a new restaurant prototype cost to develop?”

By our estimate, no less than 10,000 man-hours of development must go into creating a restaurant – whether that’s free labor from the entrepreneurs donating their time to the cause, inexpensive hourly labor who’s inexperienced in the development of prototypes, or highly experienced professionals who cost more upfront (but are more likely to get it done right the first time and save more on the back end). A lot goes into developing standards and specifications, and documenting those — a step that’s often skipped when in a hurry to get the place open.

Being accurate from the start on restaurant finance projections is critical — otherwise, it’s like a plane flying two degrees off course every minute of the flight. It will never reach the target destination.

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY IS WALKING OUT THE DOOR

Once restaurant turnover rates kick in (which is often a surprise for those outside of the industry, as the average turnover is 100% for most concepts, and for quick service restaurants (QSRs) can be as high as 300%), the intellectual property walks out the door with the employees. The documentation of standards, specifications, policies, procedures, and replicable training protocols was simply in their head and created organically, rather than formalized during the business development.

Once restaurant turnover rates kick in (which is often a surprise for those outside of the industry, as the average turnover is 100% for most concepts, and for quick service restaurants (QSRs) can be as high as 300%), the intellectual property walks out the door with the employees. The documentation of standards, specifications, policies, procedures, and replicable training protocols was simply in their head and created organically, rather than formalized during the business development.

The development of training programs is rarely listed as a line item on a restaurant start-up budget (again, even for highly experienced operators). Training costs for start-ups usually just include the cost of recruitment and the dollar amount of the hourly crew members who are being trained.

But there needs to be something the employees are being trained on. This means the standards, specifications, proprietary processes, and intellectual property need to be developed by someone. While free to low-cost templates are available on the Internet as a way to save money, making the investment upfront will yield higher returns on the back end. Most companies pinch pennies on the planning and often pay for it with a pound of flesh in run-rate performance drag.

GOOD RESTAURANTS CAN GO OUT OF BUSINESS, TOO

We’ve seen (in several instances) a restaurant become very successful after the first 3 – 4 months of opening be closed by month six. The reason being, due to underinvesting in pre-opening expenses and marketing, starting with slower-than-projected rates. As such, they begin to get behind on supplier bills and deplete their reserves.

Although they were successful and the once-empty restaurant was packed by month four, it was completely empty by month six and rented to someone else by month eight (who got all of the free equipment forfeited by the previous tenant who didn’t sharpen their pencils well enough in the development of their financial estimates, business plan, and capital budgets).

MAKING THE LEAP

We get it. If most restaurateurs and entrepreneurs knew what all was going to be involved before they made the leap, they wouldn’t do it in the first place. Some land in a lush flowerbed or splash into a crisp, cool ocean while others go splat on the rocks. But it’s not the action of jumping off the cliff; it has more to do with looking carefully and jumping off at the right spot at the right time.

Darden, the parent company of Seasons 52, reportedly invested $20 million into the prototype before the first location even opened. If restaurants cost $20 million before they open, few – if any – of them ever would. Darden, though, won’t invest in a concept unless they believe it has the potential to be a $1billion company. In that case, it makes sense to invest $20 million into a prototype that will be replicated hundreds, and bake the efficiencies in, rather than bleeding out all of that lost profit potential replicating a less-than-perfect model.

For most restaurants, if they spent what they needed to get everything right in the beginning, almost none of them would pursue opening a restaurant; but if more restaurants that did start had invested what they needed upfront, fewer of them would have closed.

PLAN AHEAD

The business plan should be allocated as a percentage of the overall capital investment (including hard and soft costs) for the development of professional feasibility study, business plan and professional guidance as it relates to brand strategy, location strategy, understanding the market and competitive dynamics, study of the trading area, financial models, and more (including, in some cases, support with the development and presentation of investor proposals and pitches).

The best restaurants are like timing a soufflé to the crescendo of an orchestra. Yet most seem like the output of a plastic bag full of groceries and candies melted together in the microwave. If we haven’t talked you out of opening a restaurant, hopefully we’ve talked you in to taking your plans out of the microwave and putting them on simmer in a nice sauce pan.

About Aaron Allen & Associates

Aaron Allen & Associates works with leaders of global foodservice and hospitality companies on strategic issues related to growing and optimizing performance and value. Specializations of the firm include multinational expansion, system-wide sales building, brand and portfolio strategy, modernized marketing, industry trends, technology, and advanced analytics. Aaron has personally led more than 2,000 client engagements spanning six continents and 100+ countries for companies collectively posting annual revenues exceeding $200 billion.

Ready to Open a Restaurant?

We Help Stack the Odds In Your Favor

Learn More