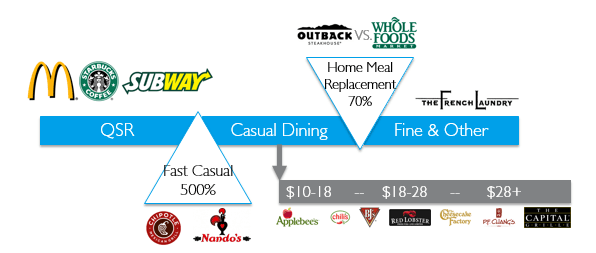

It isn’t enough to know that the fast-casual brands are eating into the market share of fast-food chains and full-service restaurants; nor is it enough to know that “fresh” has become one of the most bankable words in the F&B industry.

Why? Good question. Understanding (and asking) “Why?” is essential; and in this article, we take a deep-dive into the 10 restaurant industry trends we see as reshaping the restaurant industry, giving you the “Why?” you’re looking for.

1. Cannibalization

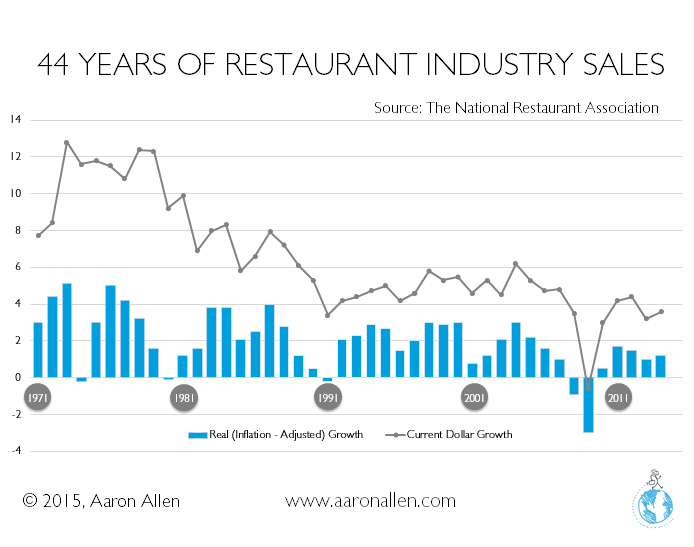

The restaurant industry is eating itself. For the last five decades, the restaurant industry has typically grown at an average rate that reflects population growth, GDP and inflation – growth that ranges from about three to four percent per year. Certain segments of the industry, however, are surpassing these benchmark industry projections by leaps and bounds, expanding at double-digit percentages with no sign of slowing (not for another several years, at the very least). Essentially, while the industry will continue to grow overall, some industry segments are being cannibalized — being eaten — by faster-growing categories. Most notably, of course, is the rise of the fast-casual segment, or limited-service restaurants (LSRs).

Fast-casual currently represents approximately $30 billion of the United States’ $700 billion total restaurant industry revenue. In less than a decade, however, the fast-casual market is projected to grow in excess of an additional $100 billion. This is one of many reasons you see heads rolling and executives sweating at restaurant chains on either side of the LSR divide — the wedge LSR brands like Chipotle are carving with a vengeance between leading quick-service restaurants (QSRs) like McDonald’s and full-service chains like Darden.

2. Henry Ford of the Restaurant Industry

The founder and CEO of Chipotle, Steve Ells, is the restaurant industry’s modern-day equivalent of Henry Ford. True, he didn’t invent the assembly line model – but Ells’ application of Ford’s revolutionary technique to the limited-service restaurant segment catapulted Chipotle to a $20-plus billion valuation (in less than a decade of going public, no less). And despite some setbacks due to a massive food safety scandal, the chain continues to reshape the entire industry both at home and abroad.

Henry Ford died in 1947. Since his passing, not a year has gone by where Ford and his ensuing model aren’t hailed as a successful case study at any community college or Ivy League university business class. When you learn about the industrial revolution, the study of giants like Eli Whitney, Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and J.P. Morgan comes standard. In the future, when students learn of the digital revolution happening now, there’s no doubt they’ll be taught the triumphs and challenges of giants like Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg.

What is a clear certainty to me, though, is that (at least in the footnotes of this point in history) scholars will give reference and well-deserved credit to Steve Ells for his role in advancing the global restaurant industry – a market currently worth five percent of the world’s GDP. To be sure, Ells’ contributions are no small accomplishment, given the impact Chipotle – a brand with locations situated (for the time being) in only 37 U.S. states – has had on the trajectory the global F&B industry. McDonald’s locations, in comparison, have a greater international presence than the U.S. military.

For this industry, the important names that came before Ells were Ray Kroc of McDonald’s, Dave Thomas of Wendy’s, Joe Lee of Darden and a handful of others. But, perhaps, no one has done more to bend the arch of the modern restaurant industry than Ells (holding aside the arguable favorite, Howard Shultz of Starbucks).

I’m not just paying homage here and flattering a living legend; I’m seeking to point out that the industry’s trajectory has been altered by this man, and he’s still quite young — the restaurant industry is only just starting to see the effects. Yes, we can say with absolute certainty, this is not a brand or a game-changer to underestimate.

ANOTHER QUICK STORY ABOUT CHIPOTLE

A friend of mine – a day trader since we graduated together – has been shorting Chipotle stock for years. In 2014, the stock started at $550 and he was sure that was finally it. After losing so much money shorting the brand, he’d double down and get all his losses back. By the summer, the stock topped at $700 per share, and my less-than-fortunate acquaintance was lugging around sofas in Denver as crew for a moving company.

Lesson? Don’t discount Chipotle. If you short their stock or CEO, keep in mind, Chipotle has just 1,800 locations in the U.S. – they have a tremendous amount of runway in front of them. This is before even applying Chipotle’s model to other segments of the industry (hint: the pizza category as you knew it is about to get a total makeover; you can thank Chipotle and those who are already applying the Ells/Ford model to pizza).

Fair warning to those otherwise destined to lugging around someone else’s sofa: if you’re looking for a stock to short, consider Shake Shack. While we love this brand, the fact Shake Shack is currently valued at $40 million per location (more than $2 billion in total, with plans to only open – by their most optimistic assumptions – 450 or so locations), is absolutely cause for caution. Chipotle, in comparison, has far more growth potential and is valued at less than one-fifth of Shake Shack’s numbers on a per-unit basis ($20 billion with 1,800 locations).

3. Chains Too Big to Change

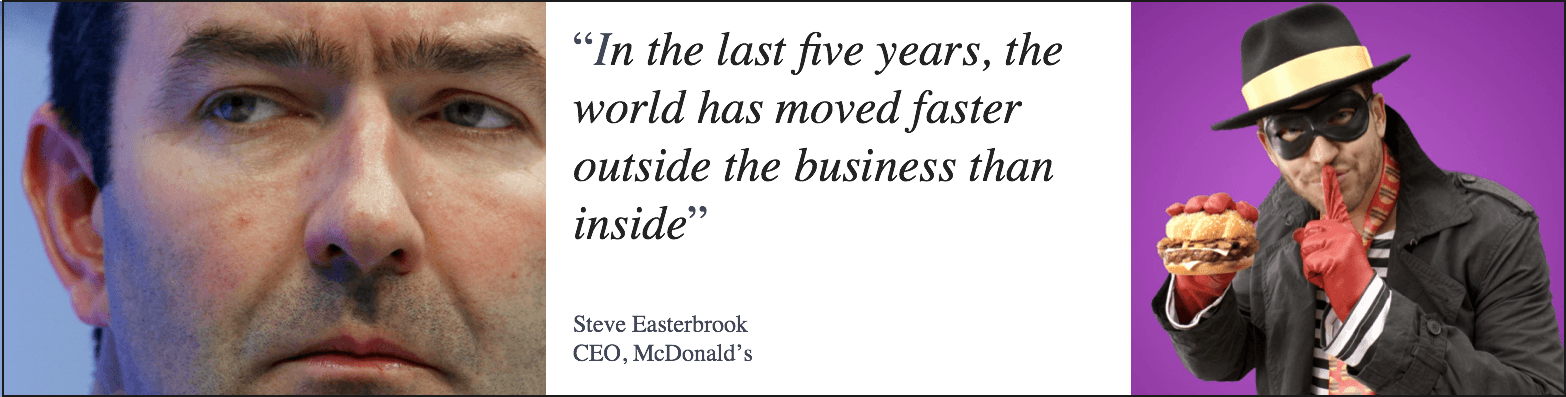

The embattled CEO of McDonald’s, Steve Easterbrook, is living this nightmare in real-time: a chain’s size – once considered a strategic advantage – has now become, in many ways, a weakness.

Even if Easterbrook has exactly the right plan to turnaround the beleaguered chain, he’ll have to convince tens of thousands of stakeholders it’s the right plan. And even if they all agree – and get all 450,000 employees bought-in and enthusiastically pulling the right direction (most of whom have never heard of Easterbrook, nor his plan, nor think about it much beyond knowing there is usually a new guy running companies like this every 18 months) – they’ll need billions more in capital than most chains do in total revenue to effectuate the changes. Even if the brand wanted to change, McDonald’s empire is simply too big.

In many cases, what McDonald’s needs to do is impossible, simply because of its size. If the brand wanted to switch to responsibly raised proteins and introduce more fresh, organic and, well, frankly, “real” food, they can’t get enough suppliers. Case in point: Chipotle – with only 1,800 locations – can’t get enough pork that meets its brand standards, so how could McDonald’s with 14,000-plus locations in the U.S. alone?

Applebee’s is another example. Imagine how hard it has been since the Great Recession to convince lenders to shell out the more than $250,000 needed per location to remodel and regain relevance. Applebee’s charismatic and admired CEO, Julia Stewart of DineEquity, Inc., only recently secured the $1 billion funding lifeline the chain needed; and the odds are still stacked against the company. Others aren’t so lucky – the money just isn’t there.

Put plainly, the industry and consumer are evolving faster than large chains can understand. Size matters, and with devastatingly slow reaction times a painful byproduct of these massive brand’s structures, key corporate decision-makers physically cannot comprehend quickly shifting landscapes, retool their sprawling systems and disseminate urgent changes all the way through an organization’s organizational chart in time.

This is why you see chains like Legal Sea Food and Shake Shack cheerfully referring to themselves as part of the new breed of anti-chain-chains. Some of the Legal Sea Food commercials are quite clever, and a spot-on response to this truth.

4. Freakonomics of Netflix

A popular documentary in Netflix is the 2010 film, Freakonomics (a movie based off of Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner’s book of the same title). In the film, Levitt and Dubner illustrate how seemingly unrelated things are often inextricably interconnected – Most people, however, fail to see the linking threads, though these unseen connections often pack a hefty economic punch – one we are absolutely witnessing in the restaurant industry. Let’s examine the freakonomics of Netflix.

A connection between movies and restaurant industry perceptions – that’s obvious. Instantly, the 2004 Morgan Spurlock film Super Size Me springs to mind. Following the film’s premiere at the 2004 Sundance Film Festival (interestingly enough, this is the same year McDonald’s started divesting Chipotle), McDonald’s removed super-sized items from its menu (though the company’s official statement was that this change had “nothing to do with that [film] whatsoever” – we beg to differ).

But let’s take a step back to review the bigger picture. In 2004, the Sundance Film Festival saw 36,656 people in attendance. In Q4 2015, Netflix alone had 57.4 million subscribers worldwide. As Netflix has grown, so too has the number of independent documentaries hitting the mainstream. Thanks to the digital streaming giant, hard-hitting critiques of America’s food system like Forks Over Knives, Food, Inc. and, yes, even Super Size Me are available to an audience that is over 1,500 times larger than the 2004 Sundance Film Festival.

Morgan Spurlock may be more responsible for changing consumer perceptions about the fast food industry than he has so far been credited. His film did have an immediate impact on McDonald’s sales, but the brand recovered (though not all brands are so fortunate…), and the attention on Spurlock’s potential influence faded as quickly, aided on by an incredible crisis communications team at McD’s (they must have departed before the latest rash of crisis communications blunders in China). Spurlock’s film inspired many other successive and successful food documentaries, though. It is the cumulative impact of all of these compelling food documentaries fueled by Netflix audiences that may have helped trigger the tipping point we’re now witnessing in America’s food system evolution.

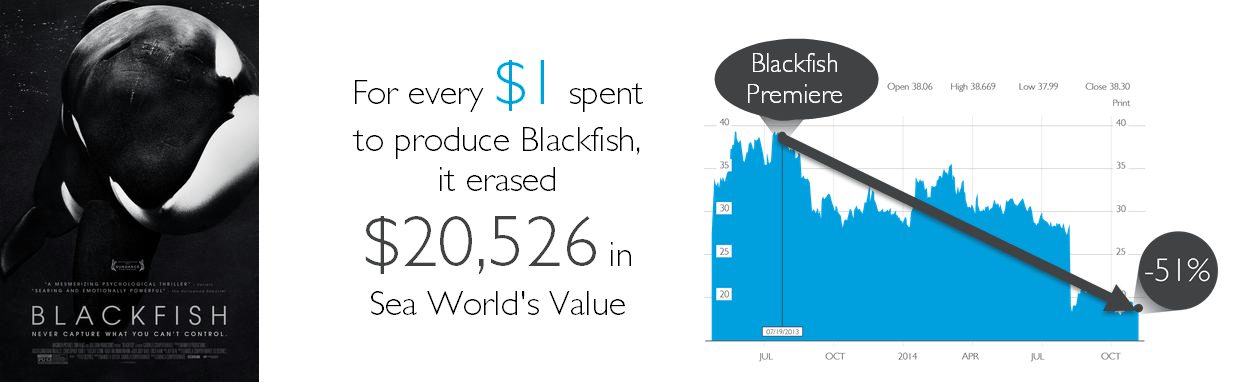

Sea World is another example of the power of Netflix distribution and the ability of mainstream documentaries to rapidly alter public opinion. Within months of the release of Blackfish, Sea World’s stock fell 51 percent, and park attendance dropped by double-digits. That’s $1.56 billion in market capitalization wiped out by an independent documentary that only cost $76,000 to make. For every dollar it cost to produce the film, it erased $20,526.32 in Sea World’s value.

5. Fewer & Fresher Ingredients

Did you know that it’s not a matter of if, but how much, pesticide is in the urine of today’s youth in America? It’s disgusting. And the more American’s learn about this and other similar crimes against nature and nutrition, the more they are demanding ingredient transparency, simplicity and greater responsibility from food manufacturers. Whether it’s taking chemicals out of fast food or removing the fuss and complexity of preparations in fine dining establishments, consumers today are making fresher foods with fewer ingredients (and definitely fewer carcinogens and chemicals) a requirement.

The most bankable word in foodservice today is “fresh.” Simultaneously, “processed” has become a four-letter word. Consumers are fed up with faux-food; and the “fresh format” foodservice operation is expected to grow at a 12 percent annual rate, while the restaurant industry as a whole is expected to grow three to four percent annually.

While Yum! Brands is looking for a pat on the back now that it has swapped out a chemical that tastes like black pepper with actual black pepper (oh, wow, you’re so progressive and ground-breaking), other chains are also jumping at the opportunity to look like good corporate citizens by reducing some of the carcinogens and chemicals masquerading as real food ingredients on their menus. In recent years, 56 percent of food companies have shortened their ingredients lists; urged on by the fact 83 percent of consumers derive health factors from the ingredients lists.

Expect your favorite and not-so-favorite food companies to tout how wholesome and pure they are becoming. It’s almost comical to watch them shoving and pushing their way onto the stage of public opinion with these kinds of modest changes, especially now that Chipotle has shown them that being a good corporate citizen can actually be good for the stock price and bottom line, too.

We will also see more emphasis on the importance of the source of ingredients, as well as a sense of place and sense of season (giving rise to more celebrity farmers like Joel Salatin, a Chipotle supplier).

It appears the perversion of our modern food system may actually be dragged into the sunlight in such a way that food companies finally turn again to farmers and nutritionists rather than chemists and food scientists, reversing a five decades trend.

6. Psychographics Over Demographics

For decades, marketing segmentation was rooted in demographic classifications. Today, it’s all about psychographic classifications. This is reshaping not only marketing, but also hiring, raising capital, and new concept development.

The classic case study for this is Coke vs. Pepsi. The best positioning you can have is to be the original; “the real thing”. The second best positioning is to be the alternative; “the choice of a new generation”. While Coke spans the generations with its marketing, Pepsi hones in on a young and youthful messaging. Now, marketing novices would argue that if you market just to a 14–24-year-old ‘demographic’, you’d be focused too narrowly and miss all of the other important constituencies. Pepsi knows, however, that youthful is not a demographic, but rather a psychographic (or state of mind). You can be old, but still want to feel – or self-identify with – young and youthful. Cher and Madonna don’t have to be young to act and identify with youthful vigor and relevance.

Now, apply this principle to the restaurant industry and you can see why restaurant chains are becoming more philosophical and espousing more of their point of view. The simple reason is – people buy brands that reflect how they see themselves (and with more than 600,000 restaurants in the US alone, it’s important to differentiate your brand and align meaningfully with the values of those you seek to attract). And the largest and more important demographic and psychographic segmentations for the restaurant industry are increasingly looking to reflect individualism, social and environmental responsibility, and an ideal of making the world a better place.

Millennials, most especially, identify with the phrase “to make the world a better place”; it’s a sentiment that resonates powerfully with them. And it’s not because of their demographic, but because of their psychographic characteristics. They’re more cause-conscience than any other demographic. And it’s easy to confuse the two. Notice how one of the best examples of modern restaurant marketing – from one of the best examples of modern restaurant industry success – comes from Chipotle with an uplifting video ending with the phrase “Cultivate a better world”.

7. Share of Stomach Wars

For the first time in all of human history, we now spend more in restaurants than grocery stores. This is a significant headline for this year (a statistic overlooked by many), but a staggering fact nonetheless. It’s like living in a fantasy time where hunter-gatherers have mobile phones and real-time alerts to document some quantum shift in their food system; like agriculture and farming systems superseding a time of throwing sticks and stones at their food. In May 2015, for the first time in our entire existence, we spent more in restaurants than grocery stores (or, by earlier equivalent, I guess, time in the field searching for berries or hunting horned animals).

So, it’s no secret that you’re more mobile than you’ve ever personally been before (and almost no matter how sedentary, you’re more mobile than any other generation in history). The more you move around and look for convenient food sources, the more food companies are scrambling to find and appeal to you.

What to expect next:

- As sales slide at grocery stores, more consumer packaged goods (CPG) food brands will look to get into the foodservice side of the business (like Chobani in NYC).

- Companies will invest more to engineer greater convenience for the modern mobile, time-starved consumer, impacting location strategy, packaging, online and mobile ordering, checkout procedures, delivery options and much more.

- Restaurants and grocery stores will continue to steal ideas from one another; with grocery stores adding more prepared foods and cafes and restaurants adding more retail items both in their own restaurants and on grocery store shelves.

8. New Unit Economic Model

The worst place to be in the restaurant business today is a full-service restaurant with a check average of less than $20. This is one reason you have been reading so much about casual-dining chains (like TGI Fridays, IHOP and others) on the low end of the spectrum getting in trouble and dragging out contrived promotional campaigns they parade around like an innovation.

The restaurant industry benefits in many ways from high unemployment rates. One of the main reasons is that for two decades – particularly when unemployment is low-polled restaurant executives routinely rank difficulty recruiting and retaining quality talent high on their lists of five biggest worries. When unemployment is high, the industry benefits from tapping into the deeper labor pool, and many employees end up staying in the industry even after the economy recovers. Now that unemployment is back to down to 5.5 percent, full-service restaurant operators will find it even more difficult to recruit and retain the more skilled workforce full-service restaurants require to operate (a condition less pronounced for limited-service operators).

In the old days, if you had $1 million, you would be happy to invest it on a one-to-one sales to investment ratio and keep a modest five percent profit; meaning, if you put $1 million in, you would expect $1 million in annual first-year sales and to keep about $50,000 in profit. Today though, fast-casual concepts can be opened for as little as $300,000 and do as much as a three-to-one sales-to-investment ratio with profits in the high teens or low twenties. For that same $1 million investment, you could potentially have three restaurants doing $900,000 in revenue each year ($2.7 million total) at a profit margin of 20 percent, netting $540,000 in annual profits.

If you have the choice, why would you spend $2.7 million to open a single McDonald’s location – or an Applebee’s – which average a one-to-one sales to investment ratio when you could take a smaller investment, diversify your risk and open three Chipotle locations?

The largest restaurant chain in the world (by number of locations) is Subway. Why? Mainly because of Subway’s very low startup cost. With fast-casual now offering similarly low cost of entry, but a much higher average unit sales volume (AUV), it’s no wonder billions of dollars are pouring into the fast-casual segment of the industry.

While Chipotle doesn’t sell franchises, it is worth noting that the average cost to open one location is $800,000, and the AUV is $2.2 million and climbing (again, by comparison, it costs $2.7 million to open a McDonald’s with an AUV of $2.4 million and sliding). Consider what $2.7 million buys you – one McDonald’s franchise unit that averages $2.4 million in revenue – OR – three (yes 3) Chipotle locations that average $2.2 million each. In other words, you could trade a $2.7 million investment with McDonald’s for $2.4 million in revenue or you could take $2.4 million ($800k x 3) to open three Chipotle locations that will combine for $6.6 million in revenue. Where would you put your money if you were investing in the restaurant industry and were faced with these facts?

This new unit economic model will continue to reshape the restaurant industry for the next decade; putting pressure on established chains and giving rise to many more emerging brands than are on our collective radars currently.

9. Industry Investment

There’s more at play than just the new unit economic model, though. We’re living in the crowd-funding era and a time where one-in-five consumers will switch brands if it’s for a ‘good cause’.

Tens of billions of dollars in restaurant industry investment has shifted around recently, and tens of billions more are expected to do the same soon.

The largest restaurant companies in the U.S. aren’t who you’d think. Many of them are actually investment banks. In fact, of the top 100 largest foodservice companies in the U.S., six out of seven of the fastest-growing are private equity firms. Ever hear of Sentinel Capital Partners? It grew 4,110 percent last year and now has restaurant holding revenues topping $762 million. It’s tiny, though, when compared to Bain Capital and Roark Capital; both of which have restaurant holdings exceeding $3.3 billion in annual revenue (Wendy’s posted just $1.5 billion in U.S. revenue during the same period, as a measuring stick).

10. Tasteful Tech

It’s hard to summarize just how much of an impact digital, social, mobile marketing, geo-location, mobile payment, and other disruptive technological innovations and inventions are having on the restaurant industry without oversimplifying or writing a book that would be outdated before it could be published. We’re all aware that technological innovations are reshaping nearly every industry, drastically altering the way we communicate and live. Taste and technology are converging in very profound ways that are leading to faster evolution of consumer dining behaviors than at any other point in history. It’s impacting every functional area of the restaurant business from menus and marketing to accounting and analytics; from how we find restaurants to how we pay our checks.

Tens of billions are being invested in restaurant-industry-specific technologies and apps right now; many of which will play significant roles in reshaping the restaurant industry over the next short few years.

While we all know this is happening, too few restaurant companies are moving fast enough to keep pace. McDonald’s has publicly acknowledged that it failed in keeping the speed of change inside the brand moving as fast as the tech-driven transformations happening outside its business. Much like the proverbial frog boiling in water, McDonald’s has moved too slowly (only begrudgingly, in some respects), and, as a consequence, the company will shrink in the U.S. for the first time in 40 years.

The trend is far, far bigger than advances made in mobile; but if we look at mobile alone, the stats are staggering. There are now more mobile phone subscribers in the world than there are people who own a toothbrush. With the average consumer now purchasing a new phone every two years and checking their phone more than 150 times per day, it’s a wonder why so few restaurant companies are investing in mobile, digital, social and technologies that can help with everything from driving revenue to cutting costs, improving efficiency, providing powerful insights into their business, and enhancing the guest experience.

Not everyone has to be in on a trend though; at least not initially. That’s part of the point. The industry is being reshaped by powerful forces – some savvy companies are creating the trends, some are pacing ahead of the trends and the late majority and laggards are, as a whole, suffering the consequences of moving too slowly.