Two of the more important metrics in understanding how a restaurant operation functions are the CAPEX-to-revenue and CAPEX-to-operating cash flow (Op.CF) ratios. These figures allow us to compare companies regardless of size, determine their long-term growth potential, and recognize their spending priorities.

Capital expenditures, which describe any one-time cost, from property and equipment purchases to remodeling initiatives and the expense of restructuring a department, are essential to long-term growth. For instance, both Texas Roadhouse and Shake Shack have been growing their footprints, either opening new units or buying land or plant facilities. Domino’s and Brinker International have been renewing out-of-date equipment, and McDonald’s and Wendy’s have launched their Experience of the Future and Image Activation campaigns to help franchisees update units.

When these investments are compared to revenue and operating cash flow, they give us important insights into a business’s operational priorities. CAPEX-to-revenue shows how much of a business’s sales are being redirected to these investments. CAPEX-to-Op.CF not only reveals the organization’s orientation toward maintaining and improving its units and equipment, but also reveals how much cash it has on hand at a given moment, giving us insights into both its current and future states.

Since the 2008–9 global financial crisis, American foodservice chains have been increasingly wary of investing in CAPEX.

The median CAPEX-to-revenue ratio of publicly traded restaurants in the US decreased in 2017 (-29%) for the first time since the recession. Though the median CAPEX-to-revenue ratio has declined steeply, this drop was mostly concentrated in lower-cap restaurants: large caps didn’t suffer a loss (their median ratio actually increased by 0.4%), but mid caps lost a median 7.3% and low caps 10.2%.

CAPEX-to-cash-flow has also declined over this period: the median ratio has decreased from a hefty 95.7% in 2007 to 52.3% in 2017, implying a 45.3% drop.

Despite these decreases, many chains are still making heavy capital expenditure investments. As we dug into the data, we found that franchise rates and segment had an effect on how much of a company’s revenue or cash flow went to CAPEX.

Large Variability in Food Service CAPEX-to-Revenue Ratios

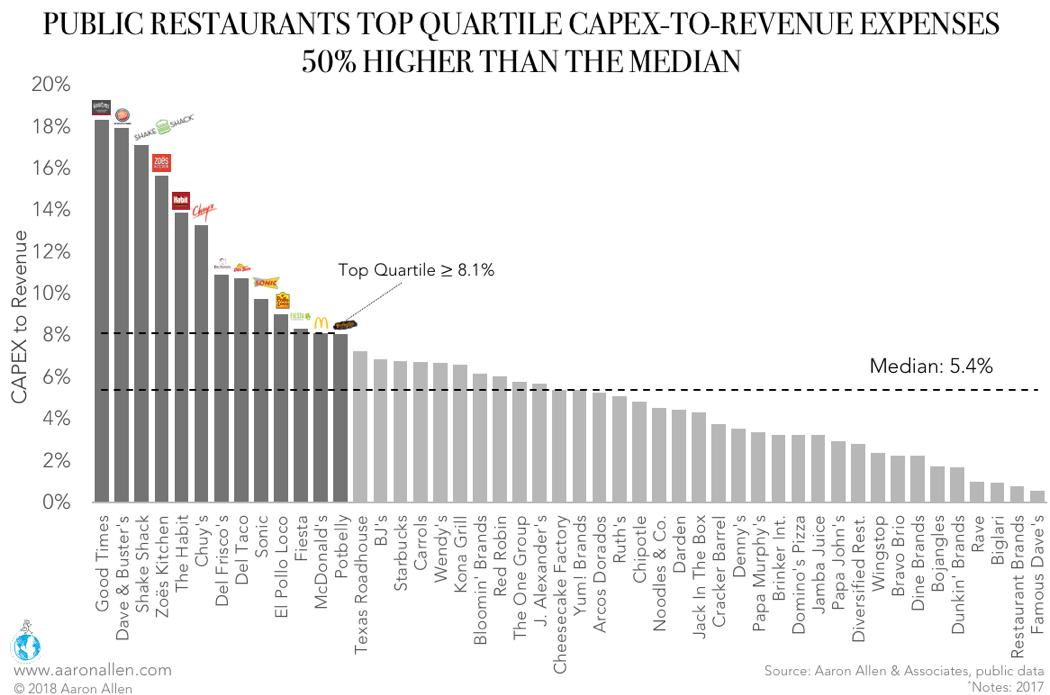

Publicly traded restaurant companies in the US have a median CAPEX-to-revenue of 5.4%.

The top quartile, however, spent 50% more. This set includes companies with low franchise levels, such as Dave & Buster’s, Del Frisco, and Chuy’s Holdings, as well as operations with highly franchised systems, such as McDonald’s, which has been investing heavily in system-wide remodels.

Publicly traded restaurants show a large variability in CAPEX-to-revenue, with companies such as Famous Dave’s and Restaurant Brands International dedicating less than 1% of revenue to CAPEX while chains like Good Times or Dave & Buster’s allocate 18% or more to capital expenditures.

Different franchising models can explain part of this variability, but not entirely. For example, Wendy’s, McDonald’s, and Dunkin’ Donuts all have high franchise rates (96%, 85%, and 100%, respectively), but very different CAPEX-to-revenue ratios. In 2017, Wendy’s allocated 6.7% of its revenue to CAPEX, McDonald’s 8.1%, and Dunkin’ Brands just 3.2%

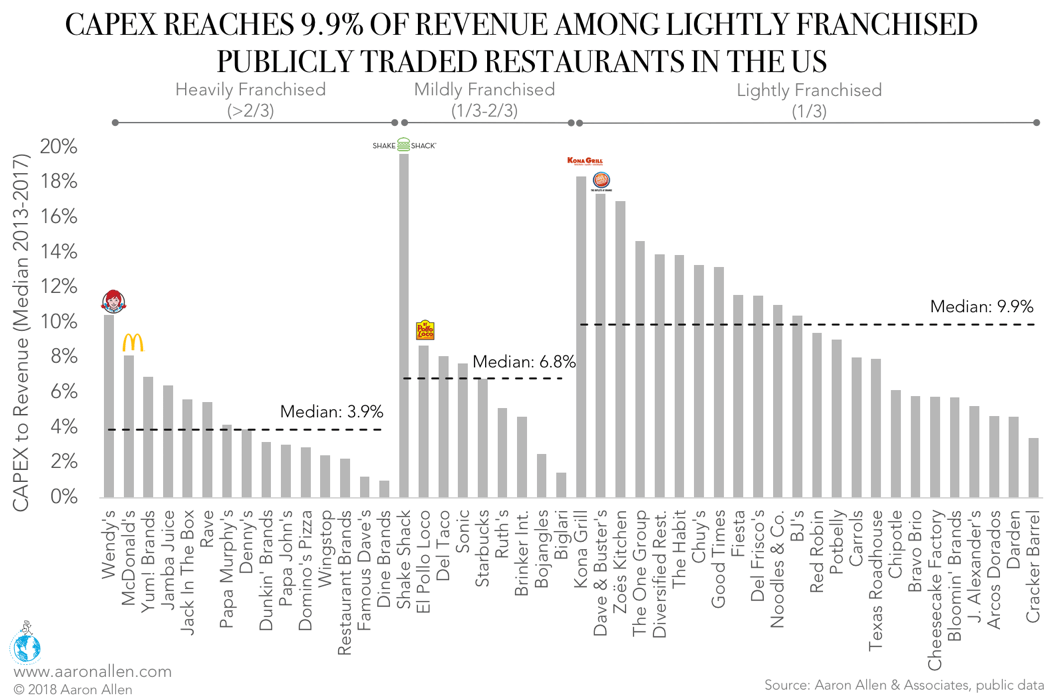

That said, breaking these companies into smaller segments based on their franchise rates does reveal some trends. Half of the publicly traded restaurant companies in the US are lightly franchised (with less than a third of their locations franchised), and 31% are heavily franchised (with two-thirds or more franchised units). The remaining 29% fall somewhere in between.

In the US, lightly franchised restaurants had a CAPEX-to-revenue median 154% higher than heavily franchised operations and 46% higher than mildly franchised chains.

However, some heavily franchised chains — especially Wendy’s and McDonald’s — have been investing large sums into store remodels and innovation on par with the investments they request from their franchisees.

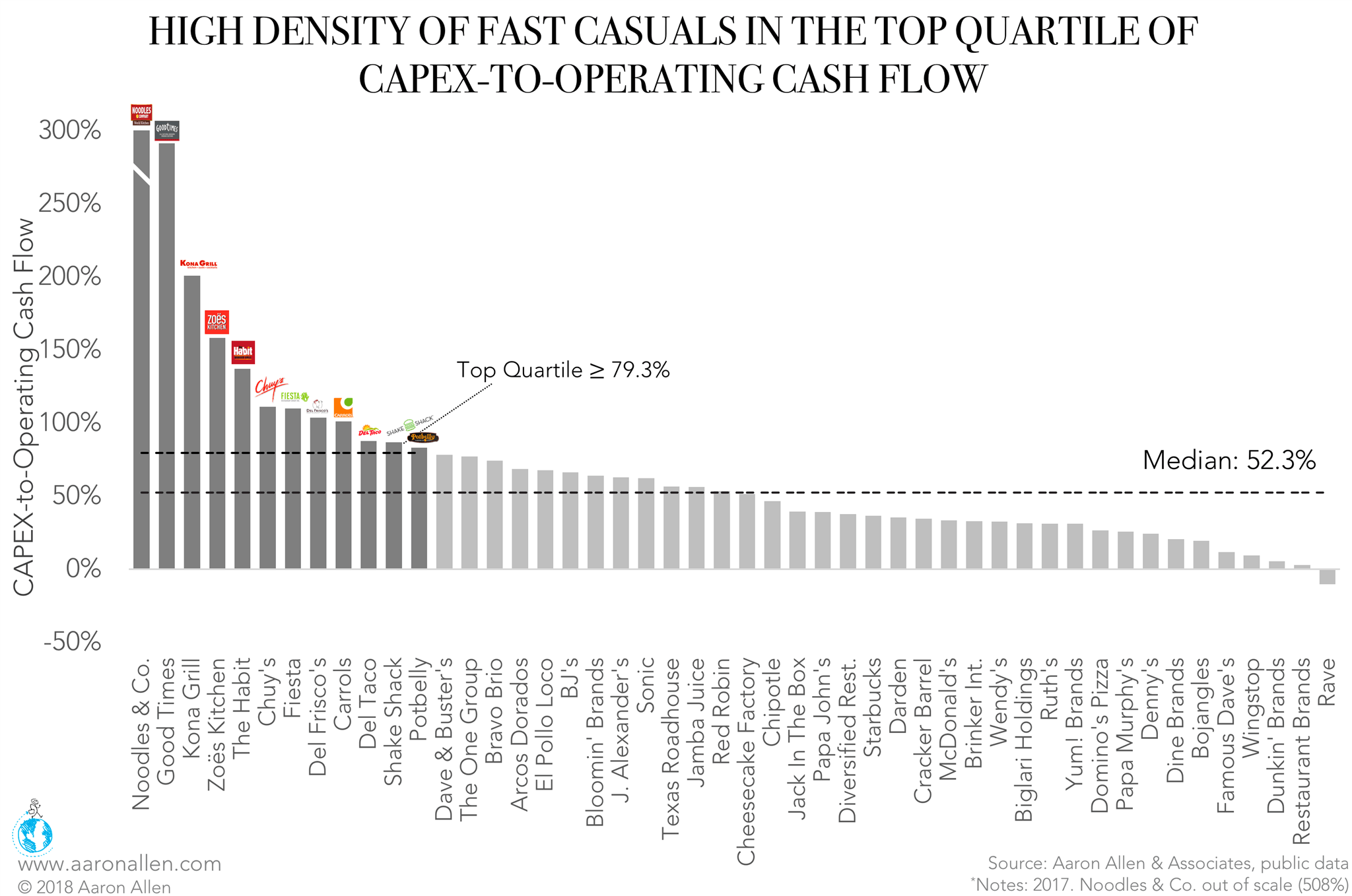

High Density of Fast-Casual Chains in Top Quartile of CAPEX-to-Operating Cash Flow

In 2017, publicly traded restaurant companies in the US spent a median of 52% their operating cash flow in CAPEX. The top quartile, however, spent at least 79.3%. This set includes a number of fast-casual concepts, including Noodles & Co., Zoës Kitchen, Habit Restaurants, Fiesta Restaurants, and Shake Shack — all of which have moderate to low levels of franchising.

As with CAPEX-to-revenue, this ratio varies significantly across segments and franchise levels.

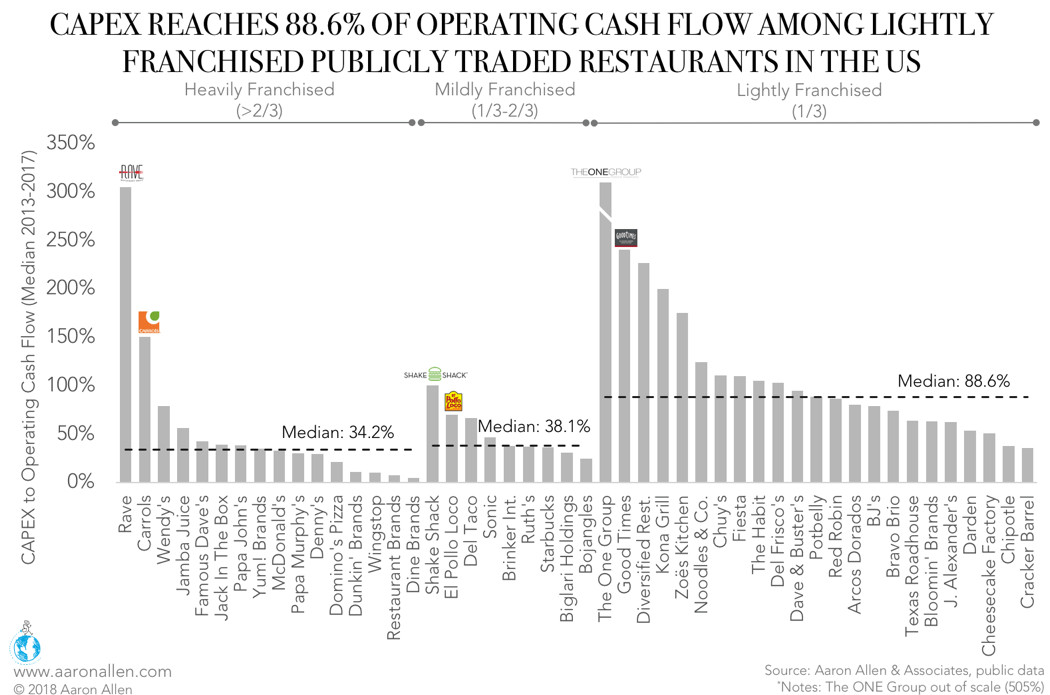

In the US, CAPEX-to-Op.CF for lightly franchised restaurants reached a median of 88.6% between 2013 and 2017, higher than that for heavily and mildly franchised companies — as we would expect.

Across operating models, we found companies without enough operating cash flow to pay for their CAPEX: Rave Restaurant Group, Carrols, The ONE Group, Good Times Restaurants, Diversified Restaurant Holdings, Kona Grill, Zoës Kitchen, Noodles & Co., Chuy’s, Fiesta Restaurants, and The Habit Restaurants.

Refranchising Reduces CAPEX Obligations

The recent refranchising fad may explain some of this decline. Some of the biggest global chains, including McDonald’s and Wendy’s, announced plans to turn a large number of corporate-owned and operated locations into franchised units. McDonald’s stated that it plans to reach a 95% franchise rate by the end of 2019.

The refranchising model is light on assets and capital expenditures, allowing chains to relieve themselves of the costs that go into constructing, renovating, and maintaining restaurants. Selling restaurant locations to franchisees is an effective way to pass these inconveniences onto franchise partners. Wendy’s President and CEO Emil Brolick anticipates that refranchising will result in up to $475 million in pretax income and “significantly reduce future capital expenditure requirements.”

This process helps the company cut its CAPEX, but it also increases its dependence on franchisees, making the parent operation’s livelihood contingent on its franchise units success and cooperation.

There’s no perfect formula for CAPEX-to-revenue or -to-Op.CF ratios. Nor is there a correct ratio of franchised to company-operated units. These strategies become the right ones to pursue when they support the operation’s overall goals. Like every investment and operational decision, these choices cannot be made in a vacuum but as part of a larger — and longer — strategic plan.

ABOUT AARON ALLEN & ASSOCIATES

Aaron Allen & Associates is a leading global restaurant industry consultancy specializing in growth strategy, marketing, branding, and commercial due diligence for emerging restaurant chains and prestigious private equity firms. We work alongside senior executives of some of the world’s most successful foodservice and hospitality companies to visualize, plan and implement innovative ideas for leapfrogging the competition. Collectively, our clients post more than $200 billion in sales, span all six inhabited continents and 100+ countries, with locations totaling tens of thousands.