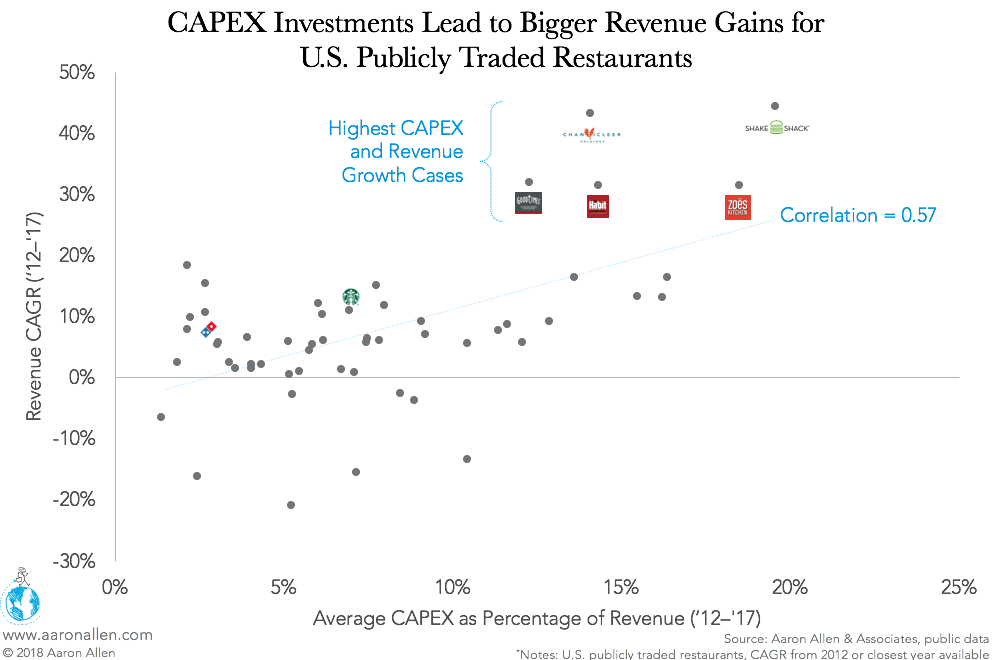

Capital is cheaper and more available than ever, and at least in the U.S. corporate profits are at record levels. Many organizations are using this opportunity to make strategic acquisitions or to increase stock prices by buying back shares and paying out larger dividends. But the strong correlation between CAPEX investments and revenue growth argues for a different strategy: putting capital back into the system.

- Public restaurants in the U.S. that spent 10.4% or more on CAPEX between 2012 and 2017 experienced an average of 11.9% revenue growth, almost twice the 6.0% average CAGR.

- Despite being able to delegate the costs of new units, remodels, and upgrades to franchisees, highly franchised systems still devote an average 5.9% of their revenue to capital expenditures.

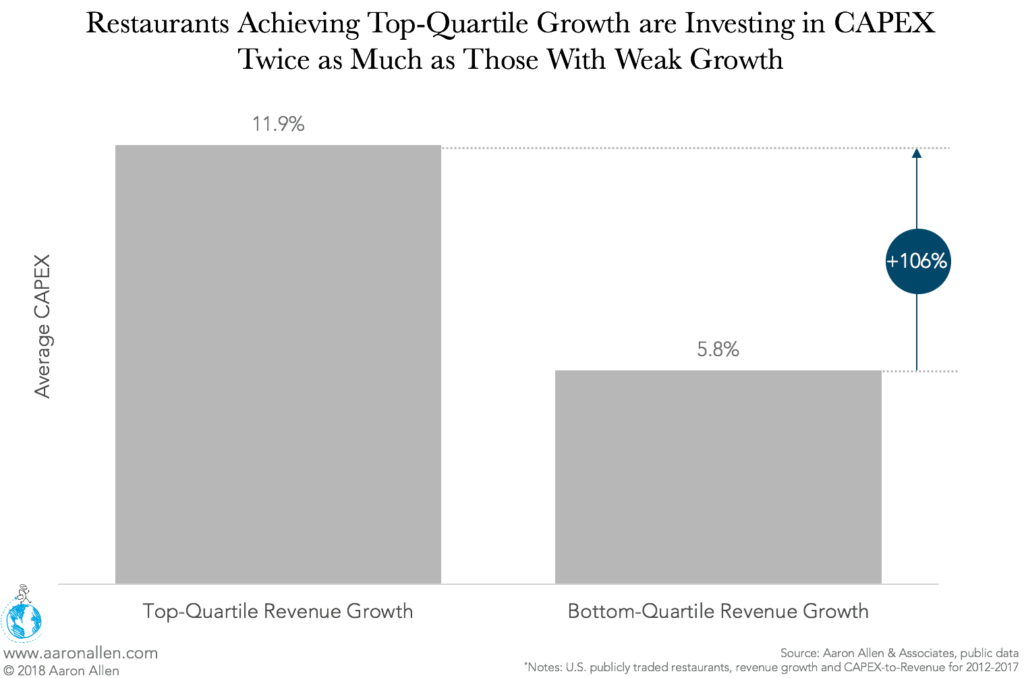

Top-Quartile Performers Double Spend on CAPEX, Earn 6.6x Revenue Growth

Public restaurant companies with top-quartile CAPEX spend (10.4% of revenue, as opposed to about 6.1%) experienced revenue growth improvements at an average of 5.9 percentage points.

Average growth for top performers was 11.7%, while in the bottom quartile that figure sinks to 1.8% CAGR. CAPEX appears to be decisive: top-quartile companies spent twice as much (11.9% of revenue) on CAPEX as bottom-quartile organizations, who devoted only 5.8% of their revenue to capital investments.

McDonald’s Projected to Spend $2.4b on CAPEX in 2018

In 2017, CAPEX spend among publicly traded restaurants in the U.S. reached its lowest point since the Great Recession, declining 23% over the past four years.

There is a slight variance across business models. On average, highly franchised systems only allocate half a percentage point less of their revenue to CAPEX than moderately franchised systems. While this seems to contradict the model, where highly franchised chains pass the majority of opening costs onto franchisees, the difference likely comes from the fact that these are the largest systems. For example, though neither Starbucks nor McDonald’s have top-quartile CAPEX spending as a percentage of revenue, their investments account for 48% of spend for all public restaurants in the U.S.

Since the beginning of 2016, McDonald’s has spent an average $484m every quarter on CAPEX. To properly scale that figure, it is more than 21x Burger King’s average annual CAPEX allocations for 2016 and 2017. So far in 2018, McDonald’s is spending even more, with an average $600m capital investment every quarter. In a recent earnings call, CEO Steve Easterbrook explained that his goal is to “build a moat around the business.” $2.4b in CAPEX investments will do just that, protecting the QSR mainstay from most competitors.

The variance between top and bottom CAPEX investors in 2017 was 2.3x, with top-quartile spend equaling or exceeding 7.3% and bottom-quartile spend equaling or falling below 3.2%. Most likely, the companies saving revenue by not investing in CAPEX will pay for it in other ways, from lost growth to inefficiencies in their units that slow down throughput.

Not all CAPEX is created equal, and different business models recommend different kinds of restaurant investments. Three strategies — new-store openings, system-wide remodels, and tech and infrastructure improvements — seem to create the most revenue growth.

CAPEX Strategy One: New Store Openings

Lightly franchised systems invest 6.0% of revenue in CAPEX, much of it devoted to opening new locations and updating existing units. For younger and smaller systems, adding more units, if supported by a strong real-estate strategy, can quickly increase sales. Shake Shack successfully pursued this strategy, investing 19.6% of its revenue into CAPEX between 2012 and 2017. The better-burger concept’s aggressive expansion strategy netted it a stunning 44.5% revenue CAGR.

In 2017, Chipotle allocated 70% of its CAPEX funds (amounting to some $152b) on opening 183 new locations. Considering the fast-casual pioneer has yet to really pursue international expansion — it has 29 locations outside the U.S. — it’s clear that it can continue to build revenue through physical expansion, whether via company-owned units or regional master franchisees.

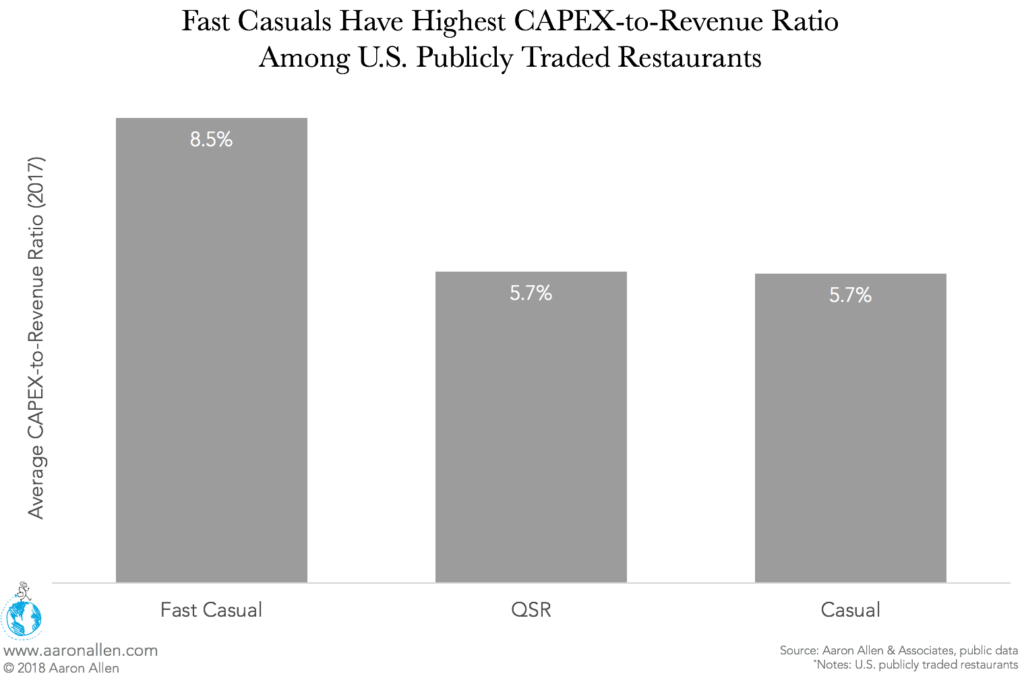

It’s no coincidence that these two examples come from the fast-casual segment, which has the highest CAPEX spend among publicly traded restaurants in the U.S.

It’s no coincidence that these two examples come from the fast-casual segment, which has the highest CAPEX spend among publicly traded restaurants in the U.S.

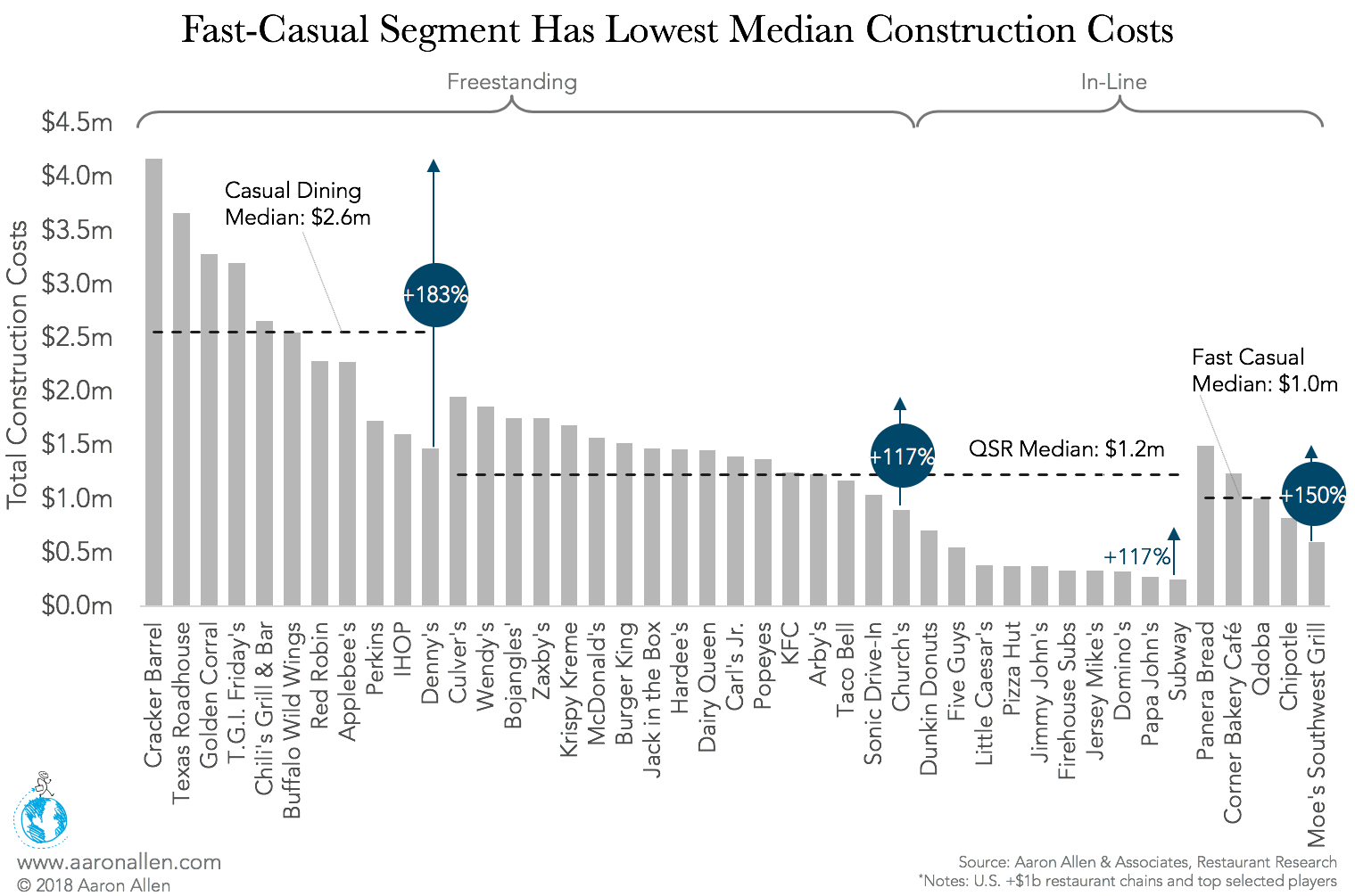

Fast-casual chains, on average, devote 8.5% of their revenue to CAPEX, almost three percentage points higher than casual-dining or QSR concepts, which both have an average CAPEX-to-revenue ration of 5.7%. This difference likely comes down to these operations’ rapid expansion strategies, as fast casual has the lowest construction costs of these three segments.

The median cost of opening a new fast-casual unit is $1m, $200k less than opening a QSR and $1.6m less than opening a CDR. Of course, there’s incredible variability within each set. The least capital-intensive quick-service chain (Subway), only requires $300k in construction, while new Panera Bread units cost $1.5m to build. (Casual dining has the widest variability, a 183% swing.) If backed by strong real-estate strategies, these construction costs can be quickly repaid through sales.

CAPEX Strategy Two: Remodels and Retrofits

Chains that have reached the limits of location saturation can still benefit from CAPEX investments in order to increase sales on the unit level through remodels and retrofits. In fact, Chipotle devoted much of the rest of its $216.8b 2017 CAPEX spend on improving existing units, and this has been a guiding strategy in Easterbrook’s turnaround strategy for McDonald’s.

In 2018, the burger chain is remodeling 4,000 of its units — a small percentage of its 36k+ locations globally but no small undertaking. It will fully transform 1,320 to the Experience of the Future design and partially update the rest. In its Q2-2018 earnings call, Easterbrook reported that even these partial remodels were bringing in mid-single digit sales lifts. While these investments can become costly, top-performing chains can realize returns on those allocations quickly.

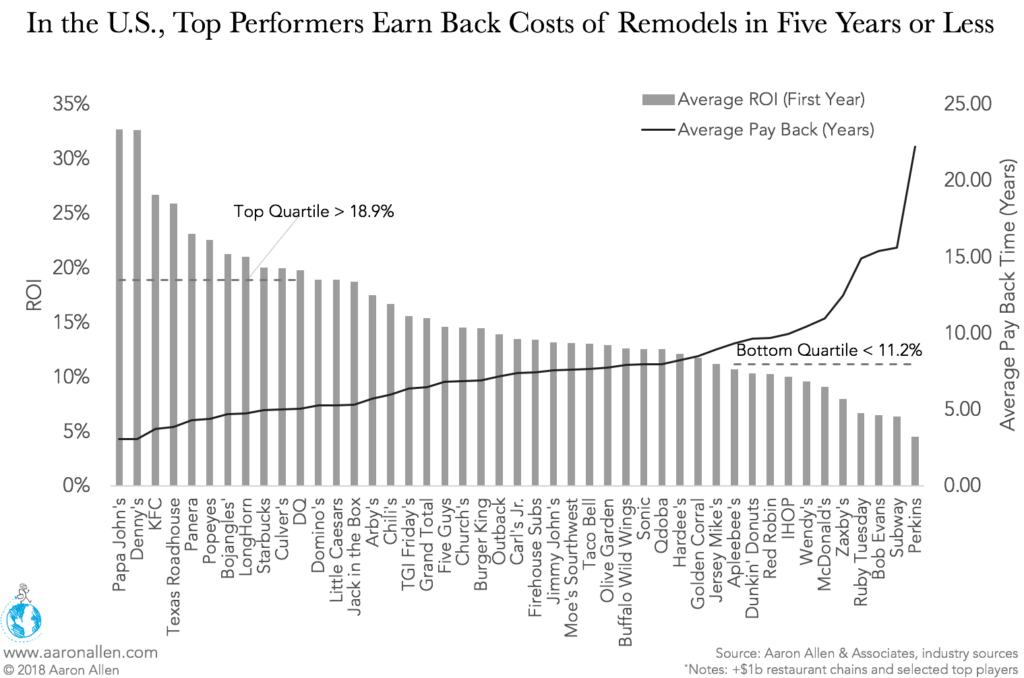

Among the largest systems in the U.S., the average ROI for remodeling and retrofitting projects reaches 15.4%. More than updating the décor, top performers use these initiatives to build productivity enhancements into the system by integrating new technologies, updating layouts (including incorporating drive-thrus), and improving signage, menu boards, and back-of-house equipment. Differences in the quality of these remodels and retrofits produces a 69% difference between top and bottom quartiles. In other words, it takes the bottom quartile 3.6 more years to recover the investment than high-performing chains.

Among the largest systems in the U.S., the average ROI for remodeling and retrofitting projects reaches 15.4%. More than updating the décor, top performers use these initiatives to build productivity enhancements into the system by integrating new technologies, updating layouts (including incorporating drive-thrus), and improving signage, menu boards, and back-of-house equipment. Differences in the quality of these remodels and retrofits produces a 69% difference between top and bottom quartiles. In other words, it takes the bottom quartile 3.6 more years to recover the investment than high-performing chains.

CAPEX Strategy Three: Technology and Infrastructure

Outside the restaurant industry, tech companies are currently engaged in what Bloomberg has called a CAPEX “war,” increasing allocations for capital expenditures 68% in Q1-2018. Amazon, for one, is projected to spend $13b in CAPEX in 2018, almost 4x its spend in 2013. More than a third of that amount, some $5b, will go to content creation, as it tries to best Netflix, which is projected to spend $8b on content). This represents more than half of the streaming service’s projected 2018 revenue, but only 5.2% of its $153b market cap.

Netflix is willing to devote so much of its revenue to content creation because it recognizes the power of investing in intangible assets. The majority of value (84%) on the S&P 500 comes from these assets, which include brand recognition, goodwill and intellectual property.

In the restaurant industry, Domino’s has followed this tech-focused strategy for the past eight years. In 2010, the pizza chain reinvented itself as a tech company that happens to sell pizza and increased enterprise value $12b in the process. Interestingly, however, one of the biggest categories of CAPEX spend in 2017 wasn’t digital or mobile, but brick-and-mortar supply chain centers. These centralized commissaries will help the chain ensure consistent — and much-improved — taste over its 97% franchised system. They also represent a significant source of income for the company: in 2017, 62% of Domino’s revenue came from its supply chain.

The other big tech investor in foodservice is Starbucks. In 2015, Howard Schulz attributed same-store sales increases to the introduction of its Mobile Order & Pay capability. The following year, the chain nearly doubled its investments in digital initiatives, increasing from $145m to $275m. In 2015, almost 20% of Starbucks CAPEX expenditures went to technology, and by the end of 2017, mobile orders accounted for 30% of all transactions.

Guest Satisfaction Has Greatest Impact on Long-Term Success

While the coffee chain’s investments kept same-store sales high through 2016, comps have started to slide, leading to the recent shake-up in top leadership. CEO Kevin Johnson explained that the reorganization was designed to “increase the velocity of innovation” at Starbucks. These comments underline how quickly consumer preferences, habits, and expectations are changing — and how hard it is to keep up. The challenge only increases in large systems, where updates to physical locations and digital assets must take place in hundreds, if not thousands, of individual units.

This news reminds us who really determines foodservice operations’ fates: the guests. Adding units to grow this customer base, remodeling existing locations to improve efficiency — and therefore guest satisfaction — and investing in technology and infrastructure are all designed with the guest in mind, so it’s not surprising to see organizations that make these capital expenditures experience above-average revenue growth.

But, as the recent news from Starbucks shows, CAPEX spend needs to be backed by careful planning. The first challenge is knowing how to right-size initiatives to the system, balancing strategy for both short-term wins and long-term priorities. The second challenge is ensuring that these investments appropriately respond to the factors and forces shaping the foodservice industry so that the organization continues to meet — and hopefully exceed — guest expectations.

About Aaron Allen & Associates

Aaron Allen & Associates works with global foodservice leaders to find, size, and seize opportunities to drive growth, optimize performance, and maximize enterprise value. Our approach to strategic restaurant planning enables our clients to understand the future of foodservice, as well as anticipate and act against the rapid evolution of disruptive technologies, evolving consumer dining behaviors, and increased competitive dynamics.